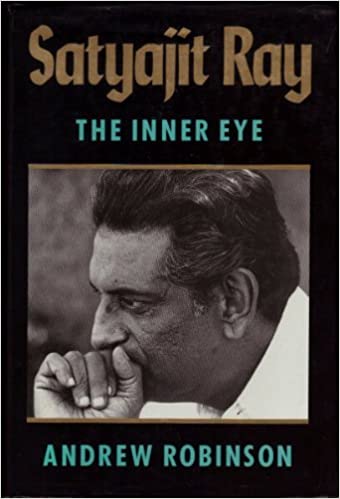

In 1955, Hollywood director John Huston visited India in search of locations for The Man Who Would Be King. While in Calcutta, Huston watched some silent rough cut of a maiden film, Pather Panchali, made by a wholly unfamiliar Bengali art director in advertising, Satyajit Ray. Huston admired it, yet advised Ray against showing too much wandering by the characters: “The audience gets restive. They don’t like to be kept waiting too long before something happens” — as Ray recalled many years later in the film magazine Sight and Sound. Huston’s recommendation of the film to the director of exhibitions at New York’s Museum of Modern Art led to its world premiere at MoMA in 1955, which launched Ray’s career internationally. As Huston told me in a letter in 1987, just before his death, while I was researching my biography of Ray, The Inner Eye: “I recognised the footage as the work of a great film-maker. I liked Ray enormously on first encounter. Everything he did and said supported my feelings on viewing the film.”

Pather Panchali, the first of the Apu Trilogy, has of course long been regarded as a classic both in Bengal and internationally, along with some other Ray films, such as Jalsaghar, Charulata and The Chess Players. They have been deeply admired by film directors as diverse as Richard Attenborough, Akira Kurosawa, Jean Renoir and Martin Scorsese. Ray was “a rare genius”, wrote Attenborough (who played a major role as General Outram in The Chess Players) on Ray’s seventieth birthday in 1991. “Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon”, said Kurosawa. “Though he’s very young still, he’s the Father of Indian Cinema”, remarked Renoir, who had encouraged Ray to tackle Pather Panchali as far back in 1949, while on a visit to Bengal. “Ray’s magic, the simple poetry of his images, will always stay with me”, commented Scorsese, also in 1991, not long before he helped to arrange Ray’s Hollywood Oscar for his lifetime achievement — his first-ever Academy award — just before Ray’s death in 1992.

Other admirers of Ray films have included artists such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, musicians such as Mstislav Rostropovitch and writers such as V. S. Naipaul and Salman Rushdie, as well as leading film critics such as Pauline Kael and David Robinson, biographer of Charles Chaplin. The Chess Players is “like a Shakespeare scene”, Naipaul told me in the 1980s. “Only three hundred words are spoken but goodness! — terrific things happen.”

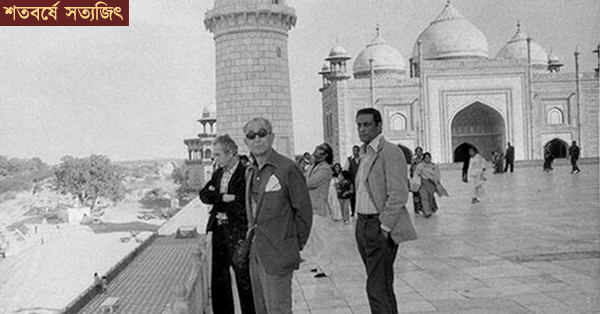

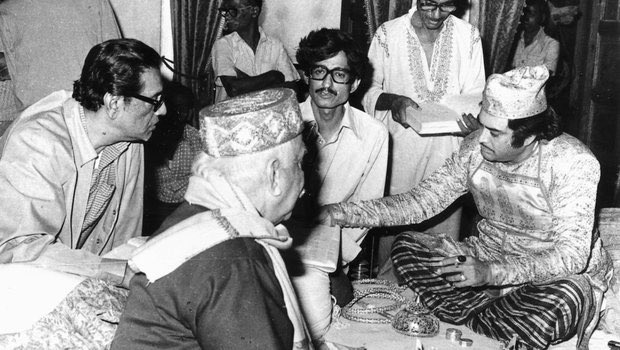

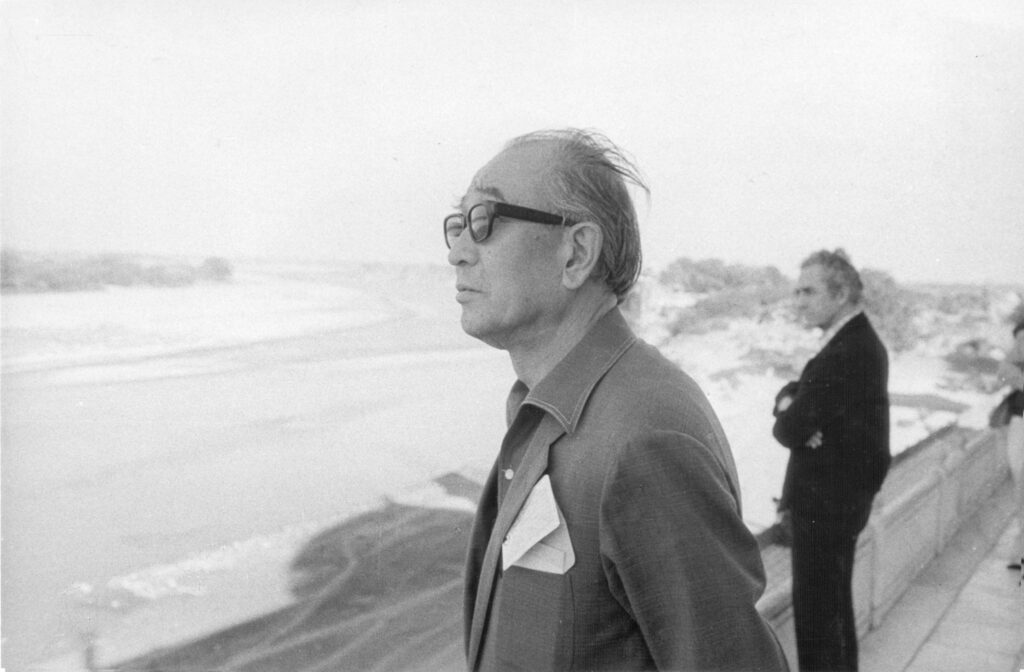

Agra, 1977

Nevertheless, Huston had a point in his private warning to Ray about pace. Many non-Bengali film-goers dismiss Ray’s films, because they find them slow. For all his awards at leading international film festivals between 1956 and 1992, Ray did not become as familiar to the western public as Attenborough, Kurosawa, Renoir and Scorsese. Even in India, his films are known principally in Bengal, not across the subcontinent, as Ray himself well knew. Hence the Indian government’s current proposal to build a major Satyajit Ray museum in Kolkata — rather than in Mumbai or New Delhi. If this ambitious dream becomes a reality, it will be only the second museum in the world devoted to a film director, after Chaplin’s World, the Swiss exhibition in Chaplin’s former house honouring an early hero of Ray.

On the birth centenary of Ray, it is worth asking why his films vary so much in appeal. Why is Satyajit Ray a genius to some, but a non-entity to many others? Most people I know personally around the world have little idea of Ray’s films, frankly speaking — including many Indians.

Agra, 1977

Several obstacles mitigate their international appreciation. First, they reflect the sophisticated and subtle fusion of East and West in Ray’s upbringing. Like Rabindranath Tagore, Ray came from a family fascinated by Western literature and thought, including science — as seen in his grandfather, the writer and technologically advanced printer, Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury. His father, Sukumar Ray, a household name in Bengali for his writing and illustrating, was influenced by Lewis Carroll (the Oxford mathematician Charles Dodgson). As a teenager, Satyajit also — unusually for Bengalis — immersed himself in Western classical music, especially Beethoven and Mozart. “I never had the feeling of grappling with an alien culture when reading European literature, or looking at European painting, or listening to Western music, whether classical or popular”, Ray said at our first meeting, in London in 1982. He was of course famously fluent in both Bengali and English. This fusion inevitably means that many aspects of Ray films are unfamiliar, offputting and sometimes incomprehensible to audiences outside India. How many international viewers will follow Ray’s pivotal pun on NASA as nesa, Bengali for ‘addiction’, in his philosophical final film, Agantuk?

Second, the films depict, chiefly, the culture of Bengal. Unlike in colonial times, during the lifetime of Ray’s great predecessor Tagore, Bengal has held relatively little economic or political importance outside India for many decades. Many Western film-goers have probably wondered why they should bother with films about Bengal — unlike, say, Japan, as depicted by Kurosawa.

Third, the films’ dialogue is almost exclusively in Bengali — which is unintelligible to most audiences, even in India. It is no accident that Ray’s non-Bengali feature, The Chess Players, made a special impact on Attenborough, Naipaul and Scorsese, who said of it: “Very few directors have been brave enough to show history in the making. This is the way it must really feel to live through a moment of historic change. It feels distant and tragic at the same time.” Certainly, I was enchanted by The Chess Players at its world premiere in 1977 at the London Film Festival in the presence of Ray; this unique occasion was a major contributor to my decision to tackle Ray’s biography. In contrast to any other Ray feature film, The Chess Players portrays British colonial rule outside Bengal partly in (excellent) English.

By way of example of the above obstacles, consider a luminously beautiful scene in Apur Sansar. When Apu’s traditionally arranged wife Aparna strikes a match to light the cigarette that he has unthinkingly put in his mouth (forgetting his promise to her to smoke only after meals), Apu notices that the flame has brought a strange and wonderful glow to Aparna’s face. “What is there in your eyes?” he asks with tenderness. “Kajal”, she answers mischievously: that is, “Kohl”, according to the film’s English subtitle. But in Bengali Aparna’s “Kajal” is also the name of the baby son she will soon bear Apu, and who will cause her death. A vital link of emotion and artistry is thereby lost on the non-Bengali viewer, for whom the pun is unavoidably untranslatable. The double-meaning could be read as the subtlest of suggestions by Ray that Apu, after long rejecting Kajal, will in the film’s finale embrace his young son, years after his beloved wife’s departure.

Lastly, Ray was multi-talented as an artist. Amazingly, he wrote the script, designed the sets and costumes, operated the camera, edited the film and composed its music, as well as directed the action. Moreover, he was of course an extensively published and very popular illustrator and writer, for both children and adults, through both magazines and books, before and after he took up film-making. Some of the witty and moving songs he composed for his films, familiar to all Bengalis, were sung by the massive Calcutta crowds that followed his body on the way to cremation, notably “Maharaja, tomare selam” from Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne. Such ‘polymathy’ — unparalleled among the world’s great film directors, even Chaplin — has provoked a natural tendency to scepticism amongst movie professionals anywhere in the world, perhaps especially in the increasingly specialised second half of the twentieth century.

Was Ray a genius (as stated by Attenborough, and many others)? Ray himself restricted ‘genius’ to only Chaplin and John Ford among film directors in his book Our Films Their Films. We are probably still too close in time to judge his own true standing. Geniuses often take many decades after their deaths to be globally recognised — as happened with Johann Sebastian Bach, Tagore and even Albert Einstein. Another Ray admirer, actor Gérard Depardieu — who helped produce Ray’s penultimate film, Sakha Prasakha, in 1990 — compared his films with Mozart’s music. Mozart unquestionably inspired the intensely musical Satyajit from the 1930s. Not long before he died, Ray made a radio broadcast for the bicentenary of Mozart’s death in 1991, “What Mozart means to me”. The ensemble performance by the central trio in Charulata — Charu, Bhupati and Amal — was inspired by Ray’s love of the ensemble singing in Mozart’s operas, he said. While making Charulata in 1964, Ray compared Chaplin’s The Gold Rush to the “distilled simplicity”, “purity of style” and “impeccable craftsmanship” of Mozart’s The Magic Flute, which he called “the most enchanting, the most impudent and the most sublime of Mozart’s operas”. Each of these qualities is evident in Ray’s finest films, I think. Maybe the undoubted genius of Mozart is the most appropriate comparison for Satyajit Ray a century after his birth, despite the thoroughly Bengali ethos of both himself and most of his films: the Mozart of cinema.

(Andrew Robinson is the author of Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye, which will appear in a third edition from Bloomsbury Publishing in 2021.)