Puran, Teesta and A Rebel Stance

Twenty-two years ago, on a January day, the writer Debesh Roy was writing a preface to his novel Teestapuran. It is a short note, and before I discuss its significance, here it is in my inadequate translation:

I feel the responsibility to make something clear.

This novel is, in no way, a continuation of or sequel to my novel Teestaparer Brittanto – not just in terms of the characters and incidents in it, but also because of the story’s shape and form or its aims and whereabouts. Simplifying it for comfort or allowing oneself to afford to complicate it might take away from the independence of both these novels. I’ve been moving in the world of the river-people perhaps because I do not know the path to come out of it. Or, it’s possible that I do not want a path out of it. Or, perhaps because there is no path out of that world.

Debesh Roy writes this from ‘Shonapadma’ in Jalpaiguri on Makar Sankranti (1406 in the Bengali calendar). I share this piece of information not because that is all there is on the page where the note appears. It is because it is related to the note and to two other things that might be considered extra-literary to the novel.

The first of these is the epigraph of the novel, a Rajbangshi proverb: Din jaaye, katha roy, days go by, stories remain. ‘Katha’ is, of course, both ‘word’ and ‘story’ in Bangla. Here, coming as almost a trailer to the novel about a river-people (Roy’s phrase), it is a nod to an oral storytelling tradition where both the meanings of the word ‘katha’ meet. How many Bangla novels have ever had a Rajbangshi proverb as epigraph? Using an adage from Rajbangshi, the language of a people that the Bangla establishment is committed to proving as a dialect, Debesh Roy is doing two things very subtly: giving an oral tradition space in the written (proverbs are largely oral in origin), and showing where his political commitment lies. All of this might be obvious to those familiar with this novel, but what I find striking is how such a saying is tied to the life of a people who live by water bodies, how the rhythm of the days passing and the words remaining plays out in many versions: something is taken by the river every day, yet life is left behind.

Teestapuran is dedicated to his niece Tirna with the words: ‘Aekdin tokay ei gawlper pakey portei hawbey’, One day you’ll have to fall into this whirl of stories. I translate ‘pak’ as whirl because it conveys the relation between stories and the character of the river on which Roy has hinged the character of his storytelling. By turning to the river as metaphor repeatedly, he is claiming history for a region and a people denied that by the fixity of the written archive.

Every novel set around the river Teesta is not a novel about the same people, just as every novel set in Calcutta is not another Calcutta novel. His preface is therefore resistance to the idea of characterising writing from North Bengal or about the Rajbangshis. By drawing attention to the difference in form and shape between the two novels, both set around the Teesta, Roy is suggesting the many possibilities in writing about this region and its people.

Why is Debesh Roy doing this, and why does he need to emphasise this at the very outset? In the preface, Roy refers to his novel about the people around the Teesta without naming the book: Teesta Parer Brittanto. Though this is another novel – Roy uses the word ‘upanyas’ in the preface – about a community of people whose lives are defined by the river Teesta, yet this is not a continuation of the previous novel. This distinction is a political and aesthetic stance. Every novel set around the river Teesta is not a novel about the same people just as every novel set in Calcutta is not another Calcutta novel. His preface is therefore resistance to the idea of characterising writing from North Bengal or about the Rajbangshis. By drawing attention to the difference in form and shape between the two novels, both set around the Teesta, Roy is suggesting the many possibilities in writing about this region and its people.

It is significant that Debesh Roy calls this novel Teestapuran, taking the suffix from an ancient form of storytelling, one that has the lineage of lore but is not treated as ‘history’. The titles of Roy’s work reveal the relation between his aesthetic choice and the literary and political tradition he is arguing against. A word he has used most often for his stories is ‘Brittanto’, the most famous of which is, of course, Teesta Parer Brittanto. ‘Brittanto’, which roughly means ‘description’, is a purposive use as is ‘puran’ – to draw a distinction from a standardised metropolitan manner of understanding the novel in the twentieth century. The ‘brittanto’ and the ‘puran’ are his way of subverting the scholarly worship of the archive. Reading the Teestapuran not far away from the Teesta, as it is murdered by dams and hydel projects, I am made aware of how writers from northern Bengal have often had to swim upstream to write against the flow – to use Debesh Roy’s metaphor – of a hand-me-down literary tradition.

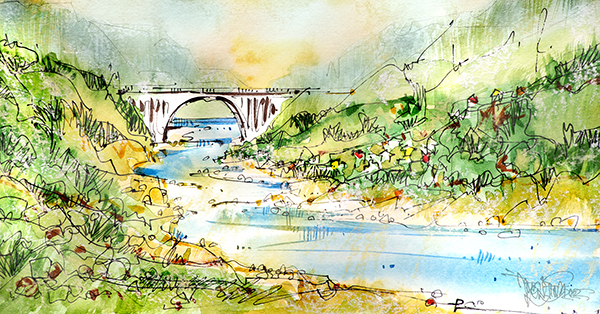

Illustration by Suvamoy Mitra