No Gods, No Heroes: Part 1

অস্কার গুয়ার্দিওলা-রিভেরা (Oscar Guardiola-Rivera) (March 18, 2021)

অস্কার গুয়ার্দিওলা-রিভেরা (Oscar Guardiola-Rivera) (March 18, 2021)How to read García Márquez today? The sixth of March marked another anniversary of the birth of Gabriel García Márquez. It is likely that rivers of ink will have flowed once more in his honour. However, we should be forgiving of anyone who comes to tell us that little or nothing new can be said about the Colombian writer.

On the one hand, the hyperbole of the languages of dominance and simulation characteristic of our societies of spectacle would have condemned García Márquez to the worst of fates: the banality of national worship and simulated personality. His work reduced to mere expository value for fascination and consumption in the enclosed spaces of the culture and literary industries.

On the other, his ascension to the status of ‘our Homer’ would sharply contrast with the ‘vargasllosism’ (after the Peruvian novelist and political opinion-setter Mario Vargas Llosa) that predominates, this one, among their successors in the next generation of Latin American and Hispanicist writers, if not as a different paradigm, at least in the sense that literature in the Spanish language (the novel, in particular) has become more productive (but not necessarily more producing). At least, as it is being practised by those who work under the aegis of what the literary critic John Beverley has termed ‘the paradigm of disillusion’.

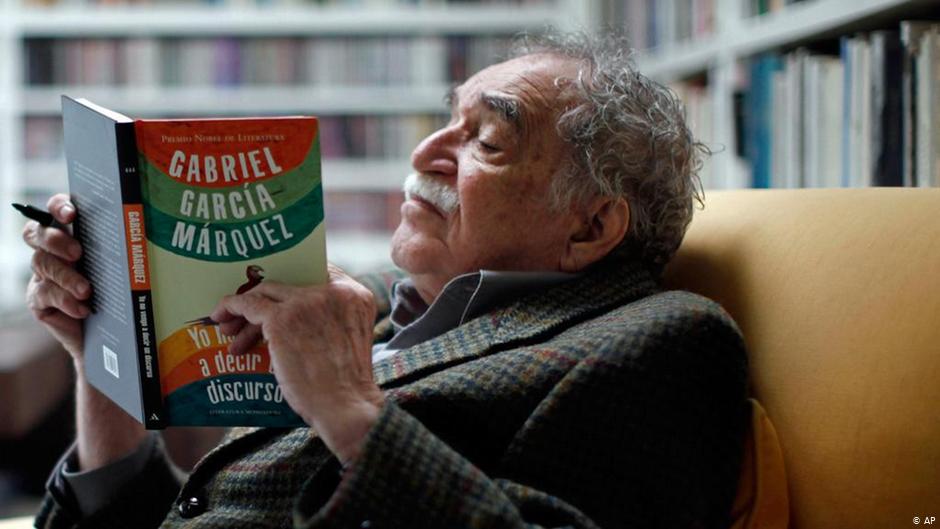

Marquez, lost in reading Beverley refers thus to the question of memory. Its meaning and function in the contemporary societies of the Americas and elsewhere. ‘How is the armed struggle in Latin America remembered today, a generation after its historical defeat or collapse?’, he asks in chapter six of his very important book Latinamericanism After 9/11. Beverley observes that this is a different question from whether one advocated armed struggle in the past or would advocate it in the present. Rather, it pertains to the work of memory in reality and the imagination.

II

We humans must make sense of existence. Not only in terms of our direct or indirect experience, but also in the sense of finding an orientation for our actions. The latter is the job of the imagination. Not to escape into the imaginary but to visualise what is lacking in the present against the possibility of its fulfilment in the future and journey back to reality in order to fulfil what may be found lacking in the current climates of history, or to transform reality. This is why we invent institutions, to bridge the gap between reality as what just is, which is always lacking, and fullness to come, real but not-yet, or justice. This is also where artistic practices intersect ethical and political discourses to provide us with directions to guide our outward-and forward-oriented actions. This does not mean such actions are guaranteed to arrive at their ‘correct’ imagined destination. There are no a priori guarantees. And yet, we must act.

In other words, no one knows the end of the story beforehand.

But that should not stop us from finding other ways to visualise, tell the story and act. However, it does seem that a tendency has emerged in recent years to disavow precisely this crucial role for invention and the imagination. Memory is now charged with providing securities and guarantees. Or hedging, as they say in the insurance and finance industry, against the risks of taking action in the present and the future. This is often justified under the pretext that we must learn from, confess and atone for the mistakes of the past. Otherwise, history will repeat itself.

This seems like an attractive idea. The idea appears to be that we should behave like the heroes of old. Upon learning about their inevitably catastrophic destiny, they would confess their mistakes and pay the price. This should not only atone for their crimes but also cleanse their souls and those of witnesses and audience from corruption or pollution. Then, they could find quiet in acceptance of the fate of humans, turn the page and move on.

In the conflict between the seemingly objective forces of the real world and human imagination, from this perspective the latter will necessarily succumb if the power was a superior power. And even if it fights against such power it will all end badly. Fighters will be punished all the same. But in confession and punishment, supposedly, human freedom and imagination would find honour and immortality. At least the frozen immortality of alethic restoration, the apparent realism of pessimism and other such temperate or colder passions: honouring, accepting and recognising what just is.

III

You don’t need me to tell you that this conception of memory, as restorative or therapeutic, corresponds to the register of tragedy. Not only the poetics of tragedy as described in the Aristotelian legacy but also the philosophy of the tragic.

The latter reached its peak during the so-called baroque period in the Americas and Europe. Roughly speaking, between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. In Germany, for instance, this understanding of the tragic that focuses not solely on its effects in the audience but on the phenomenon of the tragic itself, this interpretation of the figure of Oedipus and the Theban plays, finds its highest expression in Schiller’s 1795 Letters on Dogmatism and Criticism as well as Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. And in the Americas, later on, ideas of the baroque and the tragic would become a stand-in for denouncing the tragic way of seeing and tragedy itself as a coercive system of harmony pacification, disarming of action. And for contrasting the latter with a very different existential orientation that abhors the void, inaction, pessimism and oblivion or disavowal as well as the linear outlook, narrative and orientation of ‘harmony by numbers’, and the geometric mode of reasoning.

To insist, in the Americas these ideas of the tragic and the baroque would help people to make present contrasting versions of memory, the imagination, and productive as well as producing approaches to action in history.

At a much-loved cafe On the one hand, the standpoint of the tragic would be seen as driven by a tendency to present defensiveness or fortitude (today we would say ‘resilience’) as both ethical virtues of the familiar or the domestic and as techniques of conservation associated from early Euro-modernity onwards with expansionism, empire, conquest and the defence, conservation or restoration and productiveness of what has been gained (in conquest and battle). The city would thereafter be represented as an extension of the family. Complete with its dominant motifs of genealogy, defence (autodefensa) against external corruption and conservation, inner or confined spaces and enclosure as well as foreclosure.

On the other, there’s an emphasis on the outside. On visualising in imagination for action the Great Near and the Great Outdoors. Also, an emphasis on producers and the act of producing in and beyond the given context or the familiar. Thus, the accent is on politics, the polis rather than the oikos or the domestic. On filling what is lacking in the present spacetime. And in the practical intersection between (so-called baroque, surrealist or ‘marvellous real’) artistic practices and ethical discourses as well as warmer political passions and acts that constitute an art of and ‘in motion’, both outward- and future-oriented. The aim here is to break free from the familiar, the given limitations and margins. To break up, break free and wake up from the fantasies and nightmares of our parents.

IV

What does this have to do with Garcia Marquez? First, notice that the latter is the standpoint of Caribbean art and literature that was made explicit by Garcia Marquez and his contemporaries in the Greater Caribbean. People like Orlando Fals Borda, Marvel Moreno, the members of the Brazilian anthropophagic-Tropicalia movement, or Roberto Fernandez Retamar and Alejo Carpentier, cited above. This is the very context in which Garcia Marquez wrote.

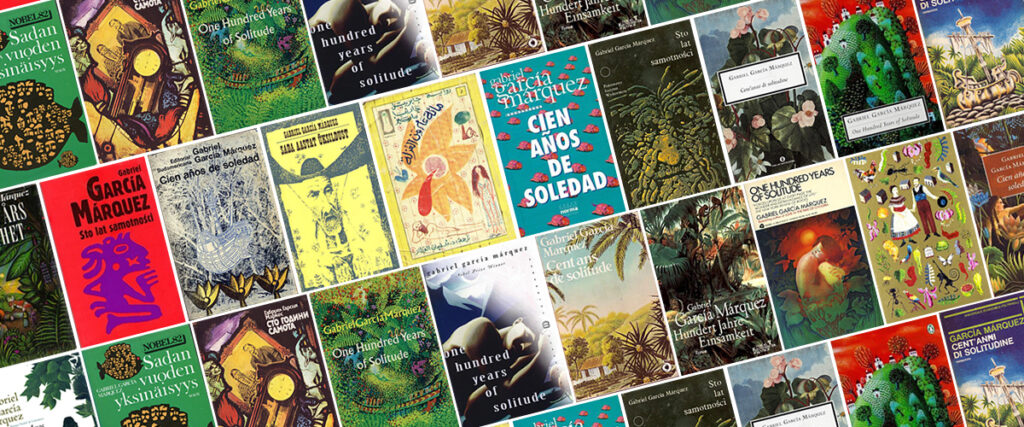

One hundred covers of editions of Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude Second, the relevant contrast here is between two ways of seeing and conceptualising the job of memory and the imagination: One, let’s call it ‘cold’, is paralysing. It leads to forgetfulness, the emptying out of the spacetime or the void; which may be productive but ends in simulation and oblivion. The other, let’s call it ‘hot’ or less temperate, abhors the void and the apparent harmony of the quiet and what just is. It calls for action, even if it is without guarantees or ‘hedged’. Like the storm sweeping Macondo at the end of One Hundred Years of Solitude. It is transformative of the present and producing of the future, even if we cannot foresee with any kind of fortress-like certitude, or to pre-empt the end as if from a Mountain of Vision.

Third, isn’t this precisely the contrast that Beverley invites us to re-visit? This is the case, at least, when he distinguishes between two forms of memory-work. One of which arguably characterised the lifework of Garcia Marquez’s generation of artists and writers (including the names mentioned above, among others) as producing. Whereas the other is perhaps very productive, but only under the terms of the ‘paradigm of disillusionment’ represented in this contrast by ‘vargasllosismo’, the currency of such paradigm in the present generation, and its sad (tragic, melancholic or pessimistic) standpoint.

You don’t need me to tell you that oblivion is a dominant theme in García Márquez’s work. Therein, it is often presented as a plague: the plague of oblivion. And you don’t need me to tell you that the coordinates of the poetics of tragedy and the tragic are present in García Márquez’s literature. Others have done that already. For instance, critics have observed the influence of Faulkner and the relationship between the tragic figure of Oedipus (and to a lesser extent, Antigone) and the construction of tragic spacetime in the work of the Colombian writer. Specifically, the tension between the enclosed and endogamic spacetime of the hero-turned-tyrant and another space, an outdoors or outside inaccessible to our eyes trained in linear perspective and/or its accompanying techniques and technologies. As these and other critics observe, such narrative construction would have allowed García Márquez to reflect upon and play with the more serious and destructive effects of civil conflict and violence. And to labour such reflections into some of the best written accounts ever put to paper.

A scene from the 2015 documentary Gabo: The Creation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, directed by Justin Webster However, in their attempts to make García Márquez’s narrative foundations fit within the canonical schemes of a history of literature assumed to be generic and universal, or at least presumed as a universal point of origin (ancient Greek tragedy, in this case) these critics tend to sideline, precisely, García Márquez’s playfulness. His humour and artistic irony. Meanwhile, they subtract such playful work from its concrete links with the Greater Caribbean and the historical trajectories that have constituted it: the literatures of the African diaspora, republican humanist modes of reasoning, tricontinental aesthetics and politics, and native forms of storytelling with visual cues, pictography, orality and song. An entire historical trajectory incarnated in the trans-continental genre of so-called ‘council literature’ and books of the people, sung, told, lived an experienced in many languages, still present rather than absent or extinct, is thereby devalued, denigrated and seemingly erased from existence. Or at least, from the record of world literature or treated as a relic of the past.

The aesthetics and politics of that period — which actually inform the protest movements we’ve seen from Santiago to Seattle during the twenty-first century years of plague — are also, thereby abstracted and represented. As mere exhibits in the museum of history or exposed as evidence to the forensic procedures of state law, judged and found guilty before the courts and the tribunals of ‘purer’ reason or settled public opinion.

Gone are, also, the ways in which the artistic practices of this producer invite us to break with and break free from, to provincialise and toy with the canonical schemes of a literary culture that assumes itself to be both universal or generic and very serious.

V

Of course, this makes García Márquez a ‘serious, so serious’ writer. And contributes to his canonisation as well as the apotheosis of modern literature written in the Spanish language. But if so, if this literature must be taken all too seriously doesn’t this also mean that it becomes stately? That is, tamed and domesticated by the nation-state and the market in all their particularity. In all their expansionist particularities.

If so, the reading of García Márquez as a stately canonical writer turns his oeuvre into the very opposite of universality.

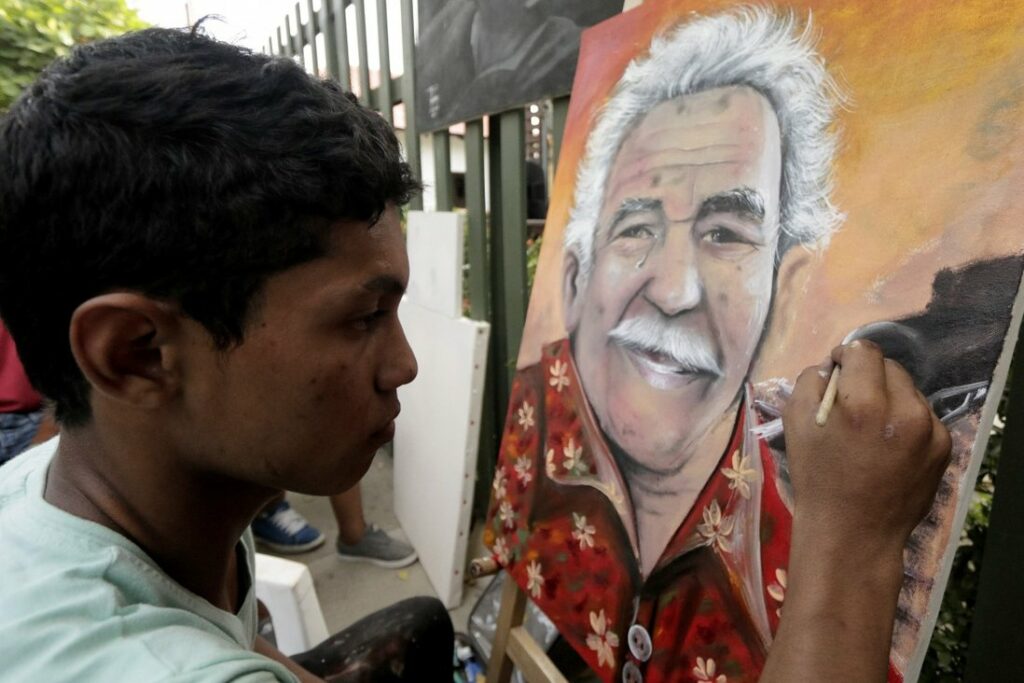

A young artist paints a portrait of Garcia Marquez in Bogota, Colombia The plain argument here is that we should not assume a certain genealogy of literature, which may be very productive on its own right, in the current context, and then, having elevated such genealogy to the status of the thing, attempt to subsume everything else under its familiar or canonical schemas as if these were producing. To notice the construction of tragic spacetime in his work may help us see the tension between the economic simulation in which the tyrant (and all of us) live, which we experience as matter of the everyday, Matrix-like, and the spacetime of the political. But this realisation, which resolves the tragic world of the tyrant into its all-too-human secular basis is not enough. For the latter detaches itself, legitimises and establishes itself as an independent realm elevated to the heights of the tribunals of history, the supposedly pure procedures of forensic reason and governance by numbers, and public opinion.

The latter must, therefore, in itself be both illuminated in its contradiction and transformed in practice.

There is a crucial distinction here between productive and producing activities. And it should be maintained. Producers make things. Which is to say, that which has value. Their activity is producing in that very plain sense. Others might engage in significant productive activities, in risking capital or making important investment and managerial decisions, and so on. But this does not entail that they produce anything in the important distinct sense in issue here. In other words, it does not entail that they engage in the activity of producing. To act productively, it is enough that one does something which helps bring it about that a thing is produced, but these activities do not entail participating in producing it.

They are not producing in the same sense in which investors (who own editorial houses, for instance) provide capital but do not produce the books they publish. This small distinction matters most if we are to make sense of the current directions and paradigms under which the act of producing a book is made productive for others. For instance, for the owners of editorial houses who may also be the owners of the newspapers in which some literary products but not others are presented as organic to the general intellect, to the established political economic interests and, in that respect, more valuable, or, indeed, canonical.

Let’s call this the settled opinion. The established opinion about literature or artistic practice as it gets combined with settled ethical and political opinion or opinion-in-the-making. As such, it is a simulation. And, therefore, distinguishable from the truth.

What is the truth here? The secret of history. That which García Márquez’s work illuminated. That only producers make the things that have value and in doing so increase the importance of all that exists. By the way, he was a leftist because he was loyal to this truth and not because of some mistaken ideological conviction.

The truth that only producers make the things that have value includes, of course, García Márquez’s novels, short stories, chronicles, essays, diaries and so on. But this is García Márquez as a humble producer, neither as a demi-god nor a hero of some duplicated universe doubled or simulated in the image and likeness of ancient Rome or Greece. That is, the universe duplicated into its secular self and the heavens of itself as an independent realm in the clouds supposedly inhabited by canonical or deified figures. Stately, serious, god-like figures. Idols.

পূর্ববর্তী লেখা পরবর্তী লেখা

Rate us on Google Rate us on FaceBook