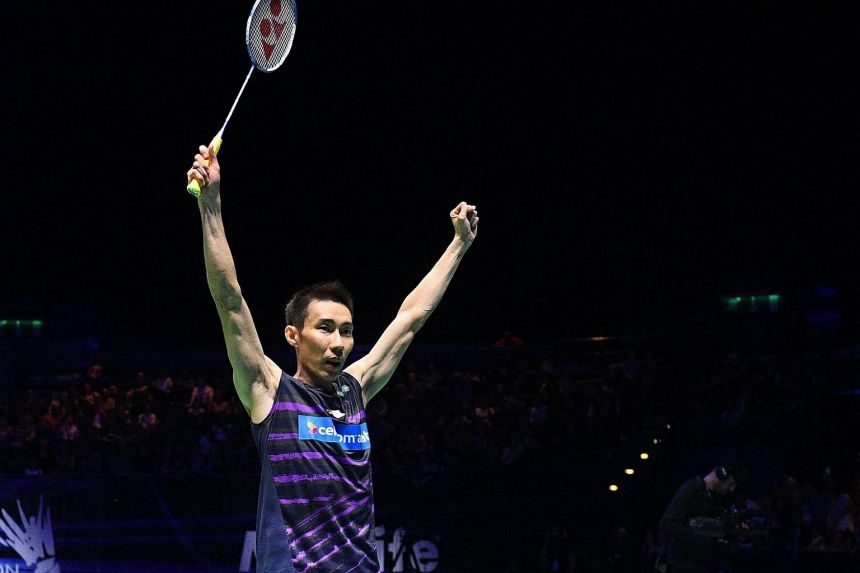

On March 14, 2001, Pullela Gopichand lifted the All-England Open trophy as the Men’s Singles champion; the second Indian to do so after Prakash Padukone’s 1980 win. Gopichand’s win, however, came with a backstory that had no parallel. In 1994, at age 20, Gopichand suffered an Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) tear that required three surgeries over two years, practically forcing his brilliant badminton career to a grinding halt. From 1997, when he made a comeback, till 2002, Gopichand was National Champion in Men’s Singles, five years in a row. He went on to win some major global tournaments, including the iconic All-England trophy in 2001, where he defeated his arch-rival, the Danish icon Peter Gade, then the World No.1 in men’s badminton, in the semi-finals. Gopichand’s five-year dream run went on without dropping a single game – both on the domestic and the international circuit. His return, and subsequent dominance in men’s badminton in the country and abroad, marks a tale of superhuman determination, defiant grit, supreme passion and total dedication — the hallmark of true champions. As the Indian team prepares to launch its 2021 All-England Open Championship campaign this week (March 17-24), ‘Gopi Sir’, the Chief National Coach, speaks to Daakbangla.COM…

What’s the first thing that comes to your mind when we refer to your 2001 All-England Open win; a landmark that changed Indian badminton forever?

I’m not somebody that keeps reminding myself or goes through what I’ve done in the past. If I look back, for me, the All-England win encompasses two things – one, it was a kind of a platform on which I could build my coaching career, and two, it was an achievement for which I will be remembered as an athlete. As a player, it’s an achievement which I am proud of.

What was the moment of the win like to you?

Honestly, it was more of a relief than happiness, because in the tournament, I was going through a lot of physical pain. There was a lot of generic stress in terms of the effort being made to perform in the tournament. It had more to do with the physical effort and the pain, and the relief after the matches was important to me, including the win in the final. The feeling was ‘Good it’s over, I am happy about it’ (laughs). Also, more than enjoying the winning moment, I was thinking and planning and hoping that I could win a lot more going over from the All-England 2001. I wasn’t satisfied, I wanted to win more.

By the time you were competing at the All-England Open championships in 2001, you had undergone three knee surgeries…

Yes, I had my struggles. Twenty years back, we didn’t have physiotherapists, no sports nutrition. Our recovery mechanisms were not as advanced as today. Those surgeries that I went through between the ages of 22 and 24 had taken a lot out of my body. Also, the 15-point format, unlike the 21-point game today, did not really allow players to play for a longer period of time, have a longer career. Back then, when you’re 25-26-27, people started to believe that you were on the downhill. I was 27 by the time I won the All-England, it was kind of looked at as being late. I was just trying to see how I could prolong my playing career.

How did you celebrate the victory, personally?

The celebration was a sense of relaxation, that I could sleep and rest for a complete day and feel okay about the body’s pain and let it recover in another two-three days. I didn’t go for a holiday. Life was so centred around sport, the holiday option or time away from sport was not a real entity. And with my injuries I already had enough breaks in my career. So that was about all the celebration I indulged in.

Everything has changed in the last 20 years – the format of the game, the surfaces that it is played on, the pace of the game. It took 21 years for an Indian to lift the All-England trophy after Padukone’s 1980 victory. It’s been 20 years since our win. When are we looking at an Indian All-England winner, man or woman?

I do believe that we have the potential in the team, I hope it is this year. Both in men’s and women’s singles, I believe some of the players in the squad have the capability to win the championship; of course, P.V. Sindhu (current Badminton World Federation Women’s Singles ranking No.7) being one of them, and maybe Srikanth Kidambi (current BWF Men’s Singles ranking No.13). I think they have the capability to win the big tournaments.

But what differentiates the All-England is the fact that the stadium that hosts the tournament (Arena Birmingham in Birmingham, England) is big, which needs you to be physically up there; that is very, very important. The physicality is what makes the All-England really the tough one. Our players have a chance. Hopefully, this year, we can celebrate.

You went into AE and won all matches in straight sets: the Round of 32 match against Colin Haughton (England) 15-7, 15-4; round of 16 match against Ji Xinpeng (China) 15-3, 15-9, the quarter-final against Anders Boesen (Denmark) 15-11, 15-7, the semi-final against Peter Gade (Denmark) 17-14, 17-15. And then in the finals you beat Chen Hong (China) 15-12, 15-6. It was almost as if it was a ‘No Game’ rule, even at the domestic level, post 1997, till 2002. How did you achieve that?

Nah, I don’t think that was a deliberate effort (smiles); given an option, I don’t think anybody wants to lose a game. It just so happened that luckily, I just managed to win those games. The more I spent time on that concrete floor at the All-England Open, the body went more sore. The faster I could finish the better it was for me. Because I won those matches in two games, I had some energy and strength left for the next few days.

Looking at the scores, it would seem that the Gade semi-final was the toughest of the tournament: was it?

Yes, it was. It was a big match. I had always lost to him in the past. To beat him in the semi-finals of the All-England Open, in a big hall, was a big thing. The match was very physical. Mentally and physically, it was a drain. He was World No. 1 and it was a tough match.

Ji was the reigning Olympic Gold medallist in men’s singles. You finished him off in less than 40 minutes. How did you prepare for that one?

I think out of all the players, the Chinese was one of the easier ones. I had beaten him in the past quite comfortably; in fact, we met four or five times in my career and he didn’t win on any of those matches. So, although he was the Olympic champion, I was rather comfortable with his style and my style.

Chen Hong was at the top of his game in the 2000-2001 season. But then, so were you; having won the Scottish and Toulouse Open titles. How did you prepare to take him on in the finals, and finally, beat him?

I think the rankings don’t really make sense playing one on one at that stage, playing an All-England final. Going into the finals, I was playing well, I was in good shape and very confident about it. Both of us had had tough semi-final matches, but he had a tougher one. He was physically drained out. All I needed to do was to deceive him enough, keep the rallies longer and tire him out, so that at some point, when he cracked, I could capitalize on it.

Your career-best ranking was World no. 4. Do you think if the knee injuries didn’t bother you and you had access to better coaching, you could have reached and retained the ranking of No.1?

I have thought about it many a times. In my mind, I have concluded that if not for the injuries, I wouldn’t have probably known that I love badminton so much, I probably wouldn’t have had the hunger to play the way I have done. For me, I think it’s the other way round; I think the injuries have been my strength. Both for my playing and my coaching career, the foundation was the tough times I had faced.

Throughout your career, who has been your arch-rival, internationally?

There were many players who were pretty strong at that point of time: Taufik Hidayat (Indonesia), Xia Xuanze (China), Peter Gade (Denmark), Hendrawan (Indonesia). Being almost the lone entry from India in some of the biggest tournaments, I had my own challenges – quality sparring partners or teammates. But I am happy with the way it all turned out. I wouldn’t really say I had played long enough to have big rivalries at the international stage, but there were quite a few of them that were tough. Also, we didn’t play as many tournaments back then, as now, with the world circuit in full flow.

Name a current men’s singles player you’d really have enjoyed playing against.

Kento Momota (current Men’s Singles BWF World No. 1, Japan) and Victor Axelsen (current Men’s Singles BWF World No. 2, Denmark) come out as the strongest players in the world today. They both bring in a level of physical and mental strength and aggressiveness on court which is amazing. I would have really loved to challenge both these guys. I admire these guys. And of course, there’s the previous generation of Peter Gade, Taufiq (Hidayat) and Lee Chong Wei, the greats. Badminton is quite fortunate that you have these greats move away and then followed by the generation of the quality of Momota and Axelsen, actually combined to take their place.

Coming to the Academy: over the past decade, it has been a hotbed of world champions. Do we, as Indians, now have a specific style, away from Southeast Asian players and the Europeans, especially the Danes?

I think it’s very difficult for Indians to ever get into that mode, because I think with most of the other countries, we are looking at the same ethnicity, a racially uniform group playing. But in India, racially, we are a diverse country. When you look at players coming from Kerala, Punjab, Bengal or Mizoram, you’re looking at different kinds of people; with mindsets, physicality, body types, strokes. It is very different for us as Indians. I focus on whatever style suits a player depending on the body type. I have also always believed that India is like this, that we will always have people with different things, and our adaptability, body type and mindset should decide what kind of style we should develop. So whether it’s a Srikanth (Kidambi) or a Sameer (Verma) or Sai (Praneeth) or Sourav or Kashyap or Prannoy (H.S) in the men’s singles squad, each of them have a different style and that’s what is India’s strength. That diversity is India’s strength.

So it is unity in diversity that we are looking at to succeed in the sport of badminton as well…

Yeah, we have to recognize that fact. The day we believe we can apply a one-size-fits-all policy to sport in India, we will fail, for sure. I think it’s important to adapt ourselves to allow that freedom to players to actually have their own styles. And that’s what’s important.

Could that All-England Open title happen sooner for India with the Men’s Doubles pair of Satwiksairaj Rankireddy and Chirag Shetty (current BWF ranking No. 10)? What would it take them to beat the best in the world right now: including the Japanese pair of Hiroyuki Endo/Yuta Watanabe (current BWF ranking No. 6) and the Indonesians, including ‘The Minions’ Marcus Gideon/Kevin Sukamuljo (current BWF ranking No.1) and ‘The Daddies’ Hendra Setiawan/Mohammed Ahsan (current BWF ranking No.2)?

It’s not going to be far, in the next couple of years. It’s very close. For all you know, it could be this year as well.

What would be your message for budding players?

Love and passion for sport is very important. If you’re going to do this with just hard work and determination and discipline for many years, it is not going to work (smiles). If you have to love and be passionate about what you do, that’s what’s important, that is the first, the basic. Love the sport, and then the rest of the things will follow. And at each step, believe in yourself, give it all you have. The people I have seen succeed are the ones with a burning desire to succeed.