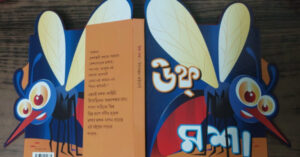

Uttar

Uttar – north; and answer. The first is obvious, but the second? Answer? The concept of answer presumes the presence of a listener, of questions that have been asked or imagined. ‘Uttar’ is therefore ‘response’. Why this need for response? It is a bit of a coincidence that I have encountered the word ‘response’ in almost every paragraph in an essay that I’ve been reading – an essay on the ‘response’ of plants to various kinds of stimuli, an essay called “The Silent Life”. Plants are silent, or so we think – Jagadish Chandra Bose wants plants to respond by ‘writing’ their torulipi, their ‘plant script’, their autobiography and their history. The north of Bengal has been a bit like that – silent, kept silent and distant from the writing traditions of Calcutta. The indifference to the life of the north seems to be coded in India’s – and Bengal’s – political imagination, and when I first read these lines from a poem by Seamus Heaney, I thought that to be the destiny of northerners:

Compose in darkness.

Expect aurora borealis

in the long foray

but no cascade of light.

The poem is called North, and I took the lines to be a homily for people like myself, of a culture of the arts and literature whose life was meant to be ignored: ‘Compose in darkness’; ‘Expect … no cascade of light’.

And so, no light fell on us. We hungered for the names of our small towns on television and in newspapers. Still largely out of the cycles of violence that bring national attention to little-known regions, we were ignored by the bad news-broadcasting machinery. We were noble savages, a phrase that would be distorted by the wife of a Philosophy professor when she, from Calcutta, said that people in North Bengal University would be jumping from trees like monkeys (she said ‘Darwin’s monkeys’, to amplify our pedigree – whether that adjective was praise or insult I still haven’t figured out). The mountains, the rivers and the sky were worth their admiration, but us? We were ‘lucky’ – that was our only talent: luck, the good fortune (never understood as choice) of living in this region.

We were satellites of Calcutta – this we had internalised without questioning. When we applied for district-based jobs, we had to go to Calcutta to write examinations and sit in front of interview boards. Even interviews for jobs at the University of North Bengal – I say ‘even’ to emphasise the location and its name – were conducted in Calcutta. Sometimes it seemed to me that that was the only reason for the existence of the Darjeeling Mail – to ferry the unemployed of north Bengal to and from Calcutta. In its coaches two kinds of conversations could he heard, and from them one could make out the residency of the speakers: ‘How can I get to Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Road from Sealdah station?’; ‘How is the weather at the moment? Chilly? Will we need a muffler?’ In that binary was our history: Calcutta was work, the ‘head’; North Bengal was play, the ‘heart’. This characterisation did not end there. It spilled over to the interviews themselves.

In a Public Service Commission interview, I was asked about the health of the Himalayas. Given that it was my first job interview, and that I was twenty-five years old, I began speaking about the mountains the way one speaks about a grandparent’s health. The next question was about the university campus: ‘Is the campus as romantic as it used to be in the 1980s?’ When I stumbled for an answer, not knowing what the campus might have looked like when I was a schoolgirl, the interviewer tried to be helpful: ‘Did you not hold your boyfriend’s hand and sing Shedin dujoney dulechhinu bonay in the sal forest on campus?’

I shook my head – I hadn’t, and, at that moment, I was angry with myself. Only if I had, they might have given the job to me.

I’ve heard versions of this from many – job applicants of colleges and universities, but also banks and engineering departments. Our roles are pre-decided from the residential addresses on our forms – we must perform the stereotype, we must play the tourist guide. It’s a tragicomedy – the anger, but also the helplessness of the situation that makes us do things against our will and belief.

Through this column, then, I will try to bring to readers our other lives – of reading, eating, writing, laughing, drawing, singing, arguing, and walking.

‘Bye-bye, Miranda,’ the interviewer on SP Mukherjee Road told me as I walked out of the door. It wasn’t me who he was characterising as much as he was where I lived – the island of Shakespeare’s play.