Meaning in Conflict

সুকন্যা দাশ (Sukanya Das) (July 10, 2021)

সুকন্যা দাশ (Sukanya Das) (July 10, 2021)The Conflict Timeline. Empathy Alley. The Memory Lab. The Sorry Tree. Installations at the Conflictorium, Ahmedabad.

Letterboxes placed along a hand-painted timeline, with reports of riots rolled tight into scrolls inside them. Life-size cutouts of the architects of India’s Freedom Movement – Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah, Ambedkar and Bose standing in two-dimensional unease – each voice ringing through the room at the flip of a switch. The unsettling similarity in the patrician tones of Nehru and Jinnah, Gandhi and Ambedkar’s less ‘elite’ accents and all their voices vibrating with conviction. A room with its sole exhibit – a much-worn copy of the Constitution of India on a raised dais. Another room where clothes snag on the exhibits – pillars of barbed wire with narrow spaces between them. And the next, where a soundtrack plays the anguished voice of a girl seeking help for threats received from her family for marrying outside the community. This tape is followed by an actual radio report of her death. An honour killing, of course. That room, reverberating with the voices of young people who literally died for love, is enough to make a visitor gasp for breath.

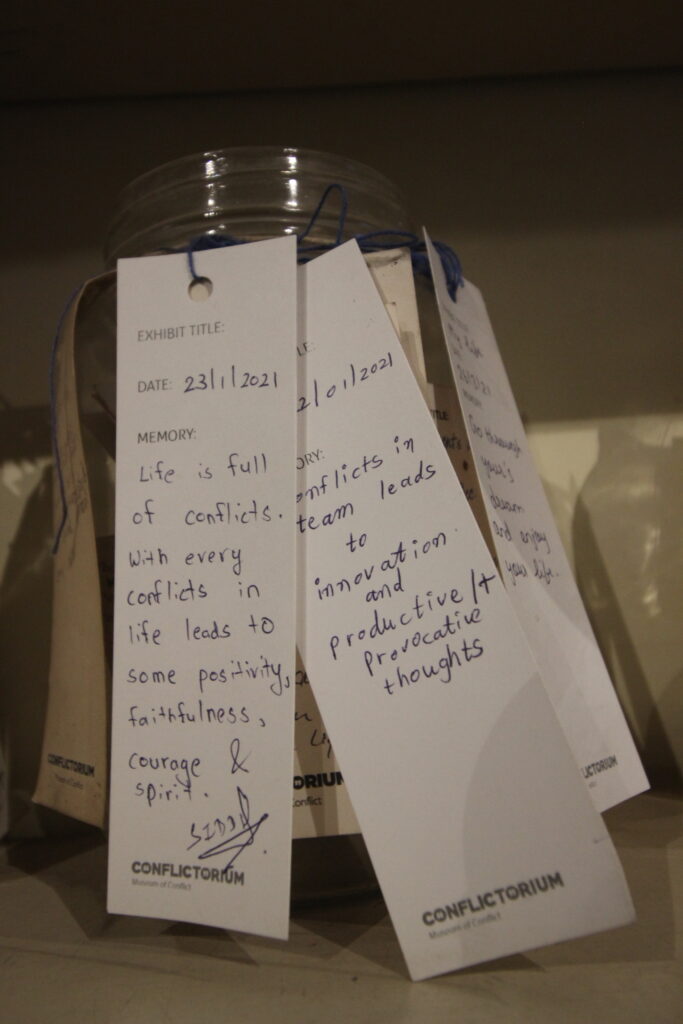

Scenes from ‘Fabricating Love and Other States’, an exhibition at the Conflictorium, Ahmedabad It doesn’t end there. If you step out onto the adjacent verandah to slow down your breathing, you will be greeted by a wall with Rohith Vemula’s last letter, with its sorry multitude of apologies. I am sorry, writes he… And the visitor is left reeling with the weight of apologies not given, and apologies not received… As the eye travels, it lights on a peepal tree with mannat strings tied to its branches. As you go closer, you notice these are little tags with ‘Sorry’ printed on one side and on the other, handwritten messages. As you look around, you will see a glass jar full of these cards. And a pen right next to it. So that you take the chance to express that long overdue apology. So that, perhaps, you experience the power of an apology. You leave the room, calmer, and as you walk into another with jars upon jars of handwritten messages, you also feel able to write what conflict means to you and to leave it there, a permanent part of The Memory Lab.

The Conflictorium describes itself as The Museum of Conflict – a memorial space that documents the incidence and significance of conflict, with special emphasis on the state of Gujarat. Political, social and personal.

Gool Lodge in Mirzapur, Ahemedabad, where the Museum of Conflict is housed The co-ordinates of the Conflictorium, housed in a building called Gool Lodge situated across the river in Mirzapur, are the first revelation about its unique nature. On the way there, the difference between the two cities on the two banks of the river Sabarmati immediately strikes the senses. While west Ahmedabad is clean, sanitised and developed to within an inch of its life, east Ahmedabad is riotously chaotic. Houses are packed cheek-by-jowl.

Bachuben Nagarwala, the last owner of Gool Lodge, operated the city’s first beauty parlour from the building. Heirless, Bachuben gave the building to the Centre for Social Justice to be used for a good cause. It was then that it passed to Avni Sethi, founder-director of Conflictorium.

The Sorry Tree, a permanent exhibit, where visitors experience the power of apology

Visitors’ notes become part of The Memory Lab, a community art installation “We must remember that the co-ordinates of the building have given it a public history as a spectator, apart from its personal life,” is Avni’s opening statement. Ahmedabad once had a large Parsi population. Mirzapur is a melting pot – essentially a Parsi mohalla, with a large Muslim population and some Hindus. Mirzapur is notorious in public perception and somewhat, in reality. Avni says, “Mirzapur is presumed volatile, and often, provoked into volatility and even violence. A stabbing happens – personal or gang-related. It is given a communal colour or gains one. A rioting mob forms, starts moving towards Delhi Darwaja. And yet again, Amdavadis hear what they hear throughout their lives – ‘dhamaal ho raha hain’, dhamaal meaning riot.”

Avni Sethi, founder-director of Conflictorium So, why memorialise conflict?

Why not, counters Avni? “If you are a body that has grown up in Ahmedabad – in the corporeal sense of the body – you have been shaped by it. As a dancer, I know that we carry our environmental and psychological experiences in every cell. Ask doctors – they will agree.” This sounds like mumbo-jumbo, but the fact of “trauma bodies” is real – trauma leaves a physical imprint, jarring memory processes and physically changing the brain.

Avni continues, “This trauma that I was unknowingly carrying around manifested itself in anger – at people and especially at happy design projects. As a release, I conceptualised this first as a project. When the logistics – space, funding –fell into place, I realised that it demanded and deserved more. So, here we are.”

Gallery of Disputes, designed by Mansi Thakkar, is a permanent exhibit Interesting as this origin story is, what is this trauma she speaks of? “Remember that Section 144 is always in effect in Ahmedabad. For years on end, people have not been able to congregate. Section 144 has been used so generously in Gujarat that we have forgotten what is ‘normal’. As a Gujarati residing in the state, I can tell you we have been beaten down into obedience. We think paternalistic authority is the only sort of government possible. Nineteen to 23-year-olds have no idea of an alternative kind of citizenship! They don’t know that one can negotiate or try to with one’s government.”

“Remember that Section 144 is always in effect in Ahmedabad. For years on end, people have not been able to congregate. Section 144 has been used so generously in Gujarat that we have forgotten what is ‘normal’. As a Gujarati residing in the state, I can tell you we have been beaten down into obedience. We think paternalistic authority is the only sort of government possible. Nineteen to 23-year-olds have no idea of an alternative kind of citizenship! They don’t know that one can negotiate or try to with one’s government.”

— Avni Sethi, founder-director, Conflictorium

It seems things are getting worse. Ahmedabad is under the Disturbed Areas Act, amended in October 2020. Many fear that this is a step towards bringing in the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), just as in Kashmir. While this remains to be seen, the amendment to DAA is undoubtedly worrying. Earlier, only areas that had witnessed (communal) riots could be notified as ‘disturbed areas’. Now, the government can notify any area as ‘disturbed area’ where it ‘sees’ the possibility of a communal riot, or of a particular community’s polarisation. That the evaluation of these ‘possibilities’ depends on the dispensation of the ruling party is clear.

The Conflictorium began with Avni’s realisation that she was not alone in needing hope and healing. “Before conflict resolution, conflict has to be faced”, says she. Representing – and forcing people to face – conflict through design is a hard task. The team feels that the aesthetics of violence have changed in the city, state and country. One can replace ‘aesthetics’ with ‘optics’ but as designers, they see everything in terms of design. “Also, can we deny that much of the violence we feel and enact as active or passive participants is a result of craft, of design?” asks Avni.

The team was clear that they weren’t setting out to ‘do art’. Their objective was to say that ‘something is not quite right’ about the city. Another deeply felt need was that they shouldn’t in the slightest way contribute to what is wrong. What form would their effort take? “All we could do is draw, paint and sing, so that was the way forward”, says Avni. The task then coalesced to represent a cross-section of ideas and diverse perspectives that work together to create an experience for the visitor.

Where does it go from here? Says Avni, “First, it just has to be. That said, now, the origin story and the originator have become redundant. Thanks to a young team that is relevant to this moment, passionate about socio-political-psychological concerns.” The Conflictorium team is NOT a group of like-minded people. The decision was to seek out people willing to fight for their thoughts and beliefs. The work atmosphere, thus, is of significant differences, if not outright conflict. Laughs Avni, “Our people fight all the time and we learn to live with a certain kind of difference. Unless the team is comfortable confronting conflict, the space cannot represent or reflect the truth of conflict at an emotional or instinctive level.”

Today, the space definitely has a life of its own. The team is committed to growing both the museum, its influence, and themselves vertically, horizontally and all around. A stated objective is helping to build Conflictoriums wherever the local populace wants one.

Today, the space definitely has a life of its own. The team is committed to growing both the museum, its influence, and themselves vertically, horizontally and all around. A stated objective is helping to build Conflictoriums wherever the local populace wants one. Other practitioners such as Dakxin Bajrange, award-winning cinematographer and director, also feel strongly about this. “All cities should have their own Conflictorium. Of course, not through a franchise model. No carbon copies,” says he. The team agrees – they use their experience and technique to ask questions of different spaces, different realities. As Communications Manager YSK Prerana informs us, the team that collaborated with Saath Charitable Trust to create the Mehnat Manzil: Museum of Work (a space that celebrates the lives of the workers of the informal sector from migration and livelihood to housing and infrastructure), was a different set. An upcoming project in Raipur will also see a different team.

The idea is to change the culture of compliance in the population. But, as Prerana says, “In the last 10 years, we do sense a change. There is a growing unease, a growing unrest. Media and social media have played a definite role in this. Now, spaces such as the Conflictorium become even more important.”

What about the Mirzapur locals? “They treat us with an amused sort of tolerance,” laughs Prerana. “They co-inhabit the Conflictorium. Children play hide-and-seek inside. It seems the Conflictorium has appeared in quite a few Tik Tok videos!” she says.

Did this acceptance, this co-inhabiting, come easily? “Frankly, it took time. We came in with an interventionist mindset. We thought of doing a comics workshop here, talking to the women there, and generally, spreading our do-gooding influence around. But, this doesn’t work. What worked is the nukkad model. We had to assure the locals subtly that we are not an intervention agency. Before doing that, we had to tell ourselves this. Repeatedly. If intervention is needed, they will come to us…” says Avni.

Information channels however are wide and open. Locals drop in casually on opening evenings. Says Prerana, “At the last opening, right towards the end, Ranjitaben (the housekeeping-in-charge) brought her family in and gave them a barefoot curatorial tour. She is engaged. That is enough and more.”

How does the Conflictorium feature in the city’s culture-scape?

Avni is firm in her belief that practitioners first need accessible infrastructure. This intrinsically garners belonging. Then, there is the question of defining audiences. She says, “Kabir Bhai (Kabir Thakore) opens up Scrapyard for Budhan – but very few come to watch. Of course that makes the Budhan team angry – but they have to fight that anger and keep coming.”

She continues, “The institutions of the city are responsible for this state of affairs. That includes families. For instance, as part of my mandated exposure to culture, why was I only taken to Darpana? Why was I not taken to Chharanagar?”

She may not have been taken to Chharanagar but Chharanagar residents have taken to the Conflictorium from their hearts. They feel that the Conflictorium belongs as much to them. “Apna jagah hain,” says Atish Indrekar, a Budhan theatre activist who uses the Conflictorium as rehearsal space. “Many people give us performance spaces, but those of us who don’t have huge living rooms or terraces, where do we rehearse? Available rehearsal spaces are even more important to struggling artistes than performance spaces,” says Atish.

All cultural spaces have canons, and all canons style themselves in certain ways to occupy certain political positions. Ahmedabad has some important culture-makers. Avni feels strongly that the presence of these icons makes it even more important for other practitioners to question. “As conscientious practitioners, we must point out flaws in our collective practice. Because, even with the best of intentions, those of us with ingrained privilege will mess up, will trip, will fall,” says she.

All cultural spaces have canons, and all canons style themselves in certain ways to occupy certain political positions. Ahmedabad has some important culture-makers. Avni feels strongly that the presence of these icons makes it even more important for other practitioners to question.

Kadak Badshahi, a production to celebrate 600 years of Ahmedabad, is an example. It seems, for costume representations, while the story was inhabiting tribal territory, the textiles looked like they belonged in the Calico Museum of Textiles. When the story moved to Ahmad Shah, the costumes became an excess of tackiness – only satin and cheap golden zari. Says Avni, “I should have asked where were your Persian textiles, where were your Banarasi brocades? Was that the only way you could communicate Islamic identity? Though I had access to Mallikaben, I couldn’t ask. She’s an icon. And that failure is mine…”

She continues, “What we need to question every single day are the quiet decisions, unconscious decisions we take or allow others to take. The Conflictorium should be a space where people experience and are then reminded to ask questions – of themselves and their communities.”

The team’s academic backgrounds in design, performance studies, and research interests in interdisciplinary practice, have equipped them to do just that — create a unique, experiential space. But the Conflictorium is more than that. It is a catalyst for socio-political dialogue and change. Says Dakxin, “Conflictorium’s importance is for someone like me who belongs to an oppressed community (he belongs to a Denotified Tribe) I feel main akele nahin hun, yaar. This gives us anger, belonging and motivation to keep working for change.”

More than the installations themselves, the museum vibrates with the emotions, responses and participation of people experiencing, feeling and healing. Team members tell us that people have screamed in front of one installation or the other. Others have wept silently for hours. We ourselves witnessed an interaction that will stay with us — a young woman in tears reached inside her tote to bring out a bottle of water as she sat down to catch her breath. The burly security person stopped her with “Aapko abhi kisi ke haath se diya hua paani ki zaroorat hai”. As the young woman looked up, bemused, her eyes raw from weeping, Ranjitaben, the housekeeper-in-charge — materialised with a steel tumbler of cool water. The young woman drank, gratefully.

It is this sensitivity that imbues this space. An atmosphere that held a strange pull – compelling us to visit every day that we were in the city, in between other appointments. The Conflictorium is not an air-conditioned space, nor is it “pretty”. It does not appeal to the senses neither does it soothe them.

Instead, it throbs like a wound, with the power of hurts and scars and the possibility of redemption. The pull and the response is visceral. And one hopes, ultimately, intellectual.

Photographs by Kushal Batunge

পূর্ববর্তী লেখা পরবর্তী লেখা

Rate us on Google Rate us on FaceBook