Nation states and modern sports are the late 19th century’s conjoined twins. It is not a coincidence that in the period when the balance of power between empires and nations begins to shift, when Germany, Italy, and Japan reorganise themselves as nation states between 1870 and 1914, that it is at this moment that modern sports formalise their rules, set up regulatory associations, and establish international competitions. This is the historical moment when athletes and sportspersons are redefined as representatives of their nations.

The first international cricket Test match was played in 1877. This was not a match played between two nations as much as an intra-imperial competition between the mother country, England, and her dominion, Australia. But being represented at cricket in a match ‘against’ England helped Australians imagine Australia as a nation. In exactly this same way did the ‘All-India’ cricket team that toured England in 1911, prefigure and embody the idea of an Indian nation in the making. (Prashant Kidambi has a wonderful book on that tour, Cricket Country, that all of us should read.)

But the relationship between newly formalised competitive sports and the nation was much larger than cricket. FIFA, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association, football’s governing association, was founded in 1904 to oversee international competition between the national associations of Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, and Switzerland. The governing bodies for football, cricket, and tennis were set up within ten years of each other, between 1904 and the outbreak of the First World War. Even a sport as individualistic as tennis was nudged into national competition in 1900 with the Davis Cup, which started life as a trans-Atlantic tournament between Great Britain and the United States of America.

The Olympics and the nationalisation of sporting competition

Even more central to the developing relationship between nationalism and sport was the nationalisation of the Olympic Games. The revived games were imagined by Pierre de Coubertin as a festival of fraternal brotherhood where the best athletes in the world competed against each other in a sporting lull, like the ancient games at Olympia where warring kingdoms observed a truce for the duration of the Olympics. What emerged was rather different.

Till the 1908 Games, entry was not restricted to teams nominated by national Olympic committees. Mixed teams participated in some team events. But from 1908 onwards, the International Olympic Association (IOA) consisted mainly of representatives of nations. The Olympics always begin with a march past of nations, each under its own placard. Alan Bairner, a historian of sport, writes that “…sport, more than any other form of social activity in the modern world, facilitates flag-waving and the playing of national anthems”. The Olympics, more than any other sporting event, has pioneered this non-stop identification of sport and the nation. As early as 1908, athletes at the Olympics became representatives of their nations as opposed to individual competitors.

There have been occasions when athletes have competed not under their national flags but under the International Olympic Association’s flag or under the flags of their National Olympic Committees, but these have always been exceptional cases to cope with civil war or national transitions or boycotts. Whenever an athlete has applied to compete as an individual the IOA has refused. When James Gilkes, a sprinter from Guyana, applied to participate as an individual to circumvent Guyana’s boycott of the 1976 Montreal Games, he was turned down. More than any other institution, the IOA made sporting competition synonymous with nationalism.

When I think back on my memories of the Olympic Games over half a century, it’s hard to be superior about hyper-nationalist fandom. It is embarrassing to acknowledge that without national narratives, the excitement of the individual striving so close to Coubertin’s heart, would have passed me by.

When I think back on my memories of the Olympic Games over half a century, it’s hard to be superior about hyper-nationalist fandom. It is embarrassing to acknowledge that without national narratives, the excitement of the individual striving so close to Coubertin’s heart, would have passed me by.

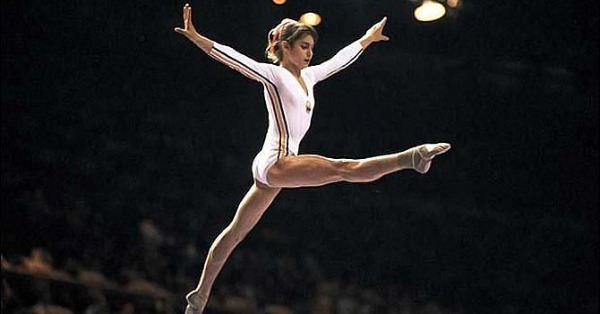

People old enough to remember the Cold War will also remember how its ideological polarisation helped spectators pick sides. The Americans rejoiced when Nadia Comaneci scored perfect 10s and pipped the Soviet gymnast Olga Korbut to gymnastic golds, because Comaneci’s country, Romania, was seen as a dissident eastern-bloc nation, hostile to Moscow. Teofilo Stevenson was an icon of Cuban nationalist pride. The decline of our hockey team in the medal rankings at the Games was a narrative of national heartbreak.

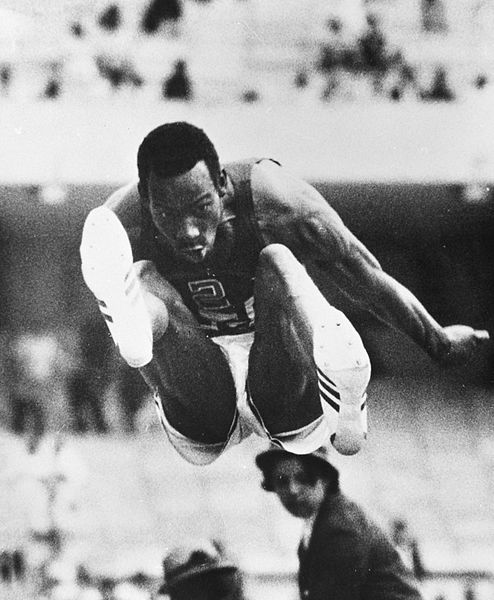

There were moments of transcendence when nationalist affiliation did not matter, like the time Bob Beamon smashed the existing long jump record by 55 cm in Mexico in 1968. Or when Dick Fosbury reinvented the high jump at the same games with the bizarre Fosbury Flop. But outside of these, the Olympics taught us that individual striving made coherent, narrative sense only in the service of national glory.

Notionally, the Games are awarded to cities, a formal gesture towards the Greek city states of old, but in effect, the Games are platforms for nations to put their best foot forward. From Berlin in 1936 to Beijing in 2008, the Olympics have been extravagant ways of announcing that the host nation has arrived.

(This an excerpt from a talk that the author delivered on Manthan in June 2021. The full talk can be heard on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2HbXohzfaSk)