Rumble in the Dangal

As the Indian contingent touches down in Tokyo for the long-awaited 2020 Olympics, India’s only double medallist in an individual sport is in police custody. Sushil Kumar, who bested his bronze medal in Beijing 2008 with a silver in 2012 at the London Games, has been arrested in connection with the murder of Sagar Dhankar, a 23-year-old wrestler. Sushil, legendary for strategy, speed and technique, is no stranger to akhara politics. His teammate and junior Narsingh Yadav failed a dope test in 2016, thus missing out on Rio. Thereafter, Yadav accused Sushil of spiking his food to sabotage his chances of making the team. The charges were not proved, but a cloud of suspicion and foul play has followed the Olympics medallist ever since.

Every now and then the Olympics reveals its darker side, where the blood, sweat and tears of honest discipline mutate dangerously into conspiracy, sabotage, even violence.

Ice Vice

Far away from the mud pits of Chhatrasal Stadium, the figure-skating rinks of USA saw a vicious attack on a young figure skater. The year was 1994, and just six weeks before the Lillehammer Winter Games, Nancy Kerrigan was assaulted with a club on her right knee as she emerged from practice a day ahead of the US National Figure Skating Championships. A win at the championships would guarantee a berth at the Olympics. Tonya Harding went on to win the championships and made the cut, and Kerrigan, too, was accommodated in the team once her injuries were diagnosed as bruises that would heal well before the Olympics.

The next three weeks saw a stranger-than-fiction string of discoveries which linked the assailants to Harding’s ex-husband Jeff Gillooly. He had hired accomplices to attack Kerrigan and pleaded guilty. While Harding pleaded ignorance, the frosty rinkside vibes between the two teammates were colder than the ice they were skating on. Harding finished eighth and Kerrigan won the silver, which made the latter the sweetheart of America for many years thereafter.

Harding pleaded guilty for ‘obstruction of prosecution’ and was banned from her sport for life. A great rivalry had curdled into a vicious enmity and the ice-skating rink had no place for it, US officials decided.

Blood In The Water

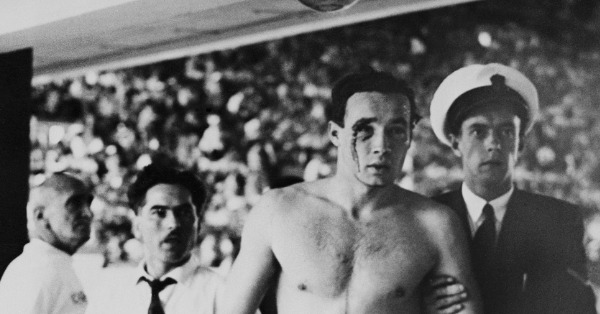

If the wrestling pit and skating rink were sullied playgrounds in these two cases, the bloodied waters of a water polo pool at the 1956 Olympics remain an uncomfortable reminder of the bitterness of the Cold War years and the intense rivalries that raged behind the Iron Curtain.

The Melbourne Olympics took place months after the 1956 uprising of Hungarian students that was quelled by the Soviets. The Hungarians were defending champions, and heard about what happened in detail only after reaching Melbourne (thanks to the control of news by the state in Hungary). In this charged atmosphere, the Hungarians took on a very tough, very physical Soviet side. The match was rough, with the Hungarians (who knew how to speak Russian) doing to the Soviets what Virat Kohli does to everybody every time he takes a catch. The abuses were verbal from the Hungarian side, but the reactions were physical from the Soviet team. Five players across the teams were evicted from the pool by the referee.

A young Hungarian, Ervin Zador, was marking an exceedingly agitated Valentin Prokopov in the dying moments of the game. As the final whistle went off, the latter smashed Zador above his eye and warm blood gushed into the pool immediately. Fans of both approached the pool menacingly as officials struggled to maintain sanity. While some witnesses claim there were fisticuffs for a few minutes and the water turned red, others claim only Zador was badly injured.

The Hungarians won gold and felt vindicated, but Zador did not return to Hungary. He went to USA and in the 1960s was coach to a certain teenager named Mark Spitz.

The Great Canadian’s Dope Trick

Doping to enhance one’s own performance is often the best way to harm all one’s opponents in one stroke, and the 1970s and 1980s were a particularly doped up/enhanced period in sport, particularly track and field. To this day, several records that were set in that period are looked upon with mistrust and scepticism.

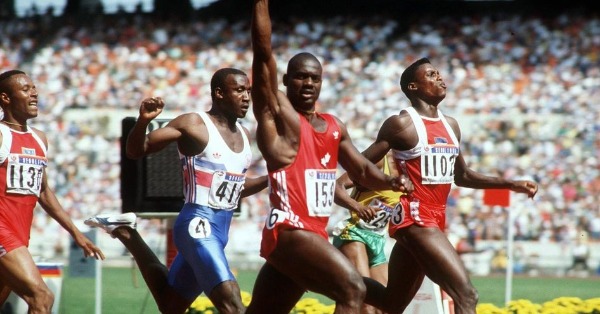

The period also saw the emergence of one of America’s greatest athletes, Carl Lewis. A symbol of being clean and yet successful, he had replicated Jesse Owens’ golden quadruple in the Los Angeles Olympics, and headed to Seoul in 1988 with a focus on defending his 100m title against Ben Johnson from Canada. Every 40-something in India will remember the live telecast of Johnson beating Lewis in a packed stadium, lifting his hand as he crossed the line to announce himself as the new king of sprint. They would also remember rumours flying thick and fast three days later, before Salma Sultan dourly confirmed on the Hindi Samachar that Johnson had indeed tested positive for banned substances. In the Pujas that followed shortly after, every Mahishasura had a marked resemblance to Johnson – the world had found its Darth Vader.

Johnson was immediately stripped of his medal (Lewis thereby succeeded in defending his ‘fastest man in the world’ tag) and subsequently of a record he had set the preceding year. In the years to come, it has been suggested that some American athletes of that era, too, were not ‘clean’. This theory was at fever pitch when Florence Griffith Joyner died of a heart attack in 1998 after retiring very prematurely. She still holds the record for being the fastest woman ever.

These are the cases of conspiracy, cheating and sabotage that were discovered. Possibly plenty more, particularly from the Cold War era, will remain undiscovered and secret for all time to come.