History sells. As does heritage. Or, so he hopes.

Thus, he makes up stories. He embellishes. To gild the real talent he, his brothers and their father share. Suresh Chitara, a Mata ni Pachedi artisan, keeps up a continuous patter as he brings out one wondrous piece after another. He is less like an artist exhibiting his work and more like a salesman. With a despairing wariness in his eyes, he steals glances at us, wondering if we have bought the story and if we will buy their work. As we sit on moras in the tiny, crumbling quarter occupied by eight family members, as we look at awe-inspiring artistry, guilt and helplessness are hard to keep at bay.

The next day, in a more ‘comfortable’ setting across the Sabarmati, Hirabhai Chauhan seems uneasy when asked how long his family has been associated with the craft of cutwork. “Kartick, my son, knows this better – all this marketing business”, he says. But this isn’t marketing, we stress. “Woh achche se bol pata hain. Call him.” When we do get in touch with his son, Kartick Chauhan mistakes us for potential customers. Again, like Suresh, he launches into a well-rehearsed speech. How his family has been practising cutwork for 400 years, how they have pieces at their ancestral home in Jamnagar that are 600 years old.

One cannot help but notice that these artisans working with lesser-known textile forms start off by trotting out spiels of ‘interesting’ family histories. Their art and their artistry are undeniable, and stunningly so. Why then, do they embroider their truth, or paint a false picture?

Uncommon crafts and usual tales

Because, they hope that these tales will help them grow sales. Neither Mata ni Pachedi nor cutwork have breached public consciousness or aspiration yet. They are not seen in emporia, nor in high-end stores.

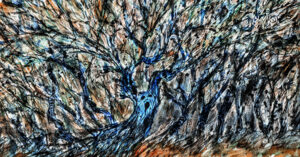

This is strange, considering any handloom lover worth their khadi kurtas knows the richness of Gujarat’s textile traditions. Bandhej is famed, as is Kutchi embroidery. Ajrakh is the latest craft that gets the pulses of the ‘handcrafted’ brigade racing and their purse-strings loosening. But, barely anyone knows about Mata ni Pachedi, where a bamboo pen and vegetable dyes are used to draw amazingly detailed pictures on cloth. And neither do they know about cutwork negative applique as practiced in Gujarat and Rajasthan, a deceptively simple technique that needs fine design sense and a precise eye for pattern.

Any handloom lover worth their khadi kurtas knows the richness of Gujarat’s textile traditions. Bandhej is famed, as is Kutchi embroidery. Ajrakh is the latest craft that gets the pulses of the ‘handcrafted’ brigade racing and their purse-strings loosening. But, barely anyone knows about Mata ni Pachedi, where a bamboo pen and vegetable dyes are used to draw amazingly detailed pictures on cloth.

Where exactly is the gap? It is for this answer that we meet National Award-winning artisans Babubhai Chitara and Hirabhai Chauhan, both of whom live in Ahmedabad. The question that is uppermost in our mind is — how long then, till these forms die?

Unpretty pictures and disparate divides

Babubhai Chitara and his three sons, Mahesh, Suresh, and Paresh make up one family among six or seven who practice the art of Mata ni Pachedi from a congested slum in old Ahmedabad. It is said that when the nomadic Vaghari community who worship the Mother Goddess (Mata) were not allowed to enter temples, they created their own places of worship with illustrations of the Mata on pieces of cloth, which they used as a background. Hence, the name Mata ni Pachedi or ‘behind the mother goddess’.

Hirabhai Chauhan’s family has been practicing the art of ‘katab’, as cutwork is locally called, for decades and probably centuries. He learnt from his grandmother, an empanelled artisan with Garvi Gurjari, the Gujarat State Emporium, and has passed on the art to his son, various nephews and the odd niece.

Does he sell to Gurjari? “No”, is the curt reply. Why not? Did the Chauhans’ work not meet some criteria, or some regulatory standards? The immediate response is an irritated “Gurjari doesn’t have any standards or plans any more. It is almost defunct as anything but a retail outlet. The only work they do is ask artisans to make samples.”

That is quite a strong indictment, considering that government emporia are supposed to bridge the gap between artisans and consumers. Under the charter of the Development Commissioner for Handicrafts and Handlooms and various State Handicrafts Boards, emporia are meant to provide design development, marketing inputs as well as retail channels.

Does Gurjari ask for samples for Mata ni Pachedi as well? Suresh says that sampling doesn’t apply for Mata ni Pachedi as it is a time-consuming, expensive form. Also, it doesn’t take easily to design development, though apparel is a slowly growing category.

How complicated — and expensive — is the process? “Hundred per cent handwork hai,” explains Mahesh Chitara, as he talks us enthusiastically through the steps. “Natural factors par depend karta hain.” For instance, water. Traditionally, the craft has always used vegetable dyes — and thus, needs running water to set. A weariness creeps into Mahesh’s voice as he says, “Earlier, we would get thigh-deep water on the banks of the Sabarmati. After the Riverfront construction, we barely get water till the ankles. The water is dirty. Earlier, we could make 50-60 pieces in one summer. Now, there’s no question.”

He continues sadly, “Colours achche nahin aate… Often, I come back home because the dirty water will affect the colour saturation.” Satisfaction is missing, he says. Something that Suresh, his younger brother, brushes away with anxious impatience. “We have to survive. Without government support, leading a threadbare existence anyway, we can’t afford to stay ‘traditional’ or ‘sustainable’ and work only when the weather and water are right! So I have changed our processes. We now work with chemical dyes. We don’t have to wait for good weather or water.” We understand the changes, and the gaps, but what next?

Livelihood learnings and life support?

Clearly, Suresh is the practical sibling — and hence, the anxious one. His eyes are tinged with worry — as if the burden of the family’s survival is on his shoulders alone. Mahesh is dreamy — a typical artist whose eyes light up when talking of his art. His pride and happiness in his work is palpable. But for Suresh, it’s desperation.

With the Chauhans though, frustration is dominant. Katab isn’t dependent on so many external factors, nor does it involve that many steps. The Chauhans are fairly prosperous. Their concern is for the community of artisans engaged in applique and the survival of the craft itself. The question is, where are the myriad government agencies tasked for the welfare of artisans?

Present imperfect and future unknown

Quite simply, they are missing in action. But, it wasn’t always like this. When people such as Safdar Hashmi, Mrinalini Sarabhai or Mallika Sarabhai were at the helm of the Handicrafts Council, it was a time of growth. “No handouts; only support. Not just exhibitions for National Award winners, but workshops for everyone. Everyone was trained in new processes. Our work was valued; they made us feel proud. Most important, nothing ‘nakli’ would be tolerated. Whether yarn, fabric, or the processes. Can you imagine the possibility of polyester in the fabrics? Screen prints being sold as block prints?” asks a visibly agitated Hirabhai.

“We used to supply 400 pieces monthly to Gurjari, going up to 1000 pieces in peak season. But we stopped because they stock rubbish now. It’s not deliberate. They simply don’t know and that’s worse,” he says.

This statement beggars belief. As part of a generation that grew up learning about indigenous handloom and handicraft traditions by loitering in emporia, this is hard to hear and harder to deny. Hirabhai continues, “People go to a government emporium for authenticity. At any cost. Emporia are supposed to be validating institutions….” How then, can this situation be retrieved?

Cluster failures and elusive tags

Maybe, by forming clusters or getting Geographical Indication tags? Is anything being done, we ask? On this, the Chitaras and Chauhans differ. For Mata ni Pachedi, it seems a committee has been formed. Suresh informs us that Khanpur, the first Chitara settlement, does not qualify as a cluster since only six or seven families practice this. “We have to make it a cluster – koshish jaari hain.” GI registration requires a list of 1200 artisans. Ever the dreamy optimist, Mahesh says, “Ho jayega – 75 per cent is through.” Cuts in Suresh, “In his dreams. We only have 64 out of 1200 artisans. But, aasha rakhte hain...”

The Chauhans say a katab cluster is impossible. The informal cluster that had formed in Vadaj because of Tejiben, the legendary applique artisan, disintegrated when she passed away. And the artisans who had learnt from Tejiben? Answers Kartick, “Boutiques in that area have spoiled the craft. They push substandard work at low rates – this devalues the work. If the government does not step in, real craftsmanship will be limited to only few and the form will be lost.”

What about national players such as Fabindia? Again, the answer is disheartening. Kartick says, “We supplied to them from 2003 to 2013. We were supplying 12000/13000 pieces per month, with a dedicated team of 200 artisans. But, because of State government regulations, orders had to come through agents. So we stopped supplying.” Is there no positive whatsoever in the outlook?

COVID crisis and customer connect

Interestingly, there is. And the pandemic had a role to play! Of course, COVID has hit the market hard. No one can travel – to the market, to the kaarigar, to the mahajans or to exhibitions. As Hirabhai says, “Everyone, especially rural artisans have been hit.”

However, the Chitaras as well as the Chauhans feel that the pandemic has helped them reach individual customers. Says Mahesh, “Earlier, it was a purely institutional-orders market, received through some government channel. Because of the pandemic, we HAD to go online. Now we know the individuals. Earlier, we did not have direct links. We were dependent on government agencies. Pehle customers ko humara naam bhi nahin pata hota.” Kartick Chauhan agrees. “The pandemic forced us to go online. Facebook and Instagram created a direct channel to potential customers. This has helped immensely,” he says.

Another unexpected plus is that youngsters have become interested in the marketing aspect. Tech-happy youngsters are eager to use social media to grow family businesses. The direct customer connect has reduced the dependence on official channels, and by extension, their helplessness and frustration. “Instagram hua to thoda sa modeling bhi kar lete hain. There is a new excitement about things,” laughs Kartick.

That there has been a bright side to the pandemic is wonderful to know. But, surely the government still has a role to play? What should that role be?

Co-work spaces and exhibition places

“We kaarigars need the government to enable us”, says Suresh Chitara. Simple, effective policies that actually benefit who they are meant for, would be a start. Three months of funding, two months of cash credit, along with some cloth credit is what will help.

Babubhai, the patriarch of the Chitara family, who has kept his silence so far says, “Look around you. How can we create art in these cramped spaces? We need a place to work. We need grants. Talent God has given us. We all work really hard. But we need cloth credit, a yarn bank. Till 2003, we used to get some work from the government, some grants as well. Now we don’t know what the scene is — it’s all murky.”

Kartik continues, “We need support with retail. The DC organises exhibitions but only for National Award winners. So, what happens to us?” Suresh adds, “Think of Ajrakh. There are 3000 artisans of the Khatri clan — but you have heard of only two or three. But, everyone has to get rozi roti. Otherwise, they will look for other avenues of employment and again, these craft forms will be lost.” With exhibition invites, awards and grants given only to National Award winners, the unasked question lingers in the air — what happens when the awardees in the family pass on?

Sensitive policies and sensible progress

Everything stops. Unless the government intervenes, maybe? Again, we ask – what help do they want from the government? “None”, Hirabhai puts in firmly, a quiet anger in his eyes. “No help. Only sensible, sensitive policies. I want to say this to the government — make policies that will make kaarigars self-sufficient; aapne unko apne haal pe chhod diya! You have abandoned us. Instead of enabling us, you are selling mill ka maal and machine ka kaam in emporia! You say Atmanirbhar Bharat — then make us atmanirbhar through policy!”

There’s really not much to say after that dignified demand. Except hope that the concerned government agencies sort out the tangles, work to create a transparent bridge, and empower those who have been making in India for generations, who continue to spin and embellish these threads of our shared history and heritage, those who carry this legacy their hands and hearts. If not, what will be lost, is without measure.