Foremost, Expression

You have written extensively on Ramkinkar Baij, as time goes by what are the aspects of his works, particularly the ones in public places, that make him such an evocative ‘kaljayi’ artist?

It is difficult to say why some artists triumph over time while others are forgotten. To a great extent, it depends on the intrinsic artistic quality of their work. By this, I don’t mean the dexterity of the artist but the work’s ability to communicate to us the human and artistic values of an epoch through its bodily materiality even after the historical exigencies that shaped it have faded.

In every epoch works that embody deeper realisations and works that merely play fiddle to the whims of the time may find equal success. But only works that embody some deeper truth can speak convincingly to an audience outside that historical moment. This does not necessarily mean that everything such an artist expresses has to be topical today but that we recognize a very strong and authentic expression in the works. Ramkinkar’s works do just that; when we look at them we recognize that he captured certain social and artistic possibilities of the place and time he worked in, in more insightful and complex ways than most other artists he is clubbed with either ideologically or temporally.

There’s often a temptation to cast Ramkinkar as a maverick, an iconoclast. However, there are stories of his being immersed in his craft, unmindful of adulation accolades. Is there truth in either of these characterisations or both?

Both are true about him.

Every artist who is more than an exalted craftsman or an upholder of a canon would be innovative or iconoclastic, as you say, to a degree; especially, when they are not working within the framework of a traditional society. As a teacher, Nandalal recommended a balance between tradition, nature, and individuality. An artist, he argued, develops skill sets through contact with certain artistic antecedents. Grounds oneself in reality through contact with the environment and becomes significant when what is gathered from art and reality is vitalised by individuality. Their balance is not a mathematical mean but the product of a dynamic interaction between them.

Like his close associates in Santiniketan Ramkinkar engaged with the local environment but viewed it through the lens of a different sensibility, and he drew his skill sets from different art traditions, this allowed him to focus upon the shared world in a personal way, or made him an iconoclast if you like.

Besides this, he was also work-engrossed like some of his close associates and unmindful of the economic and social rewards it brought. For him, art was not a profession but a way of life, and a tool to explore and to understand the world and one’s society. This meant that the real rewards were always in the future and the accolades that came his way were temporary distractions, or to put in another way small eddies in the flow.

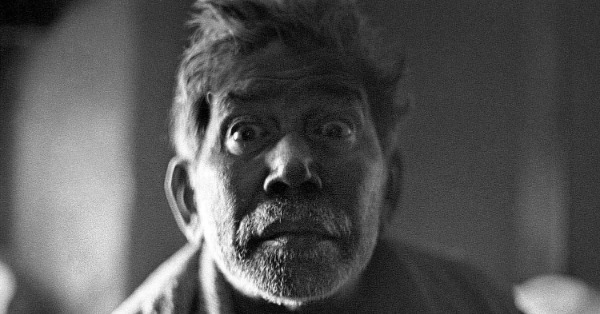

Photograph courtesy: National Gallery of Modern Art

Walking around Santiniketan the presence of Ramkinkar is a notable one. Could you tell us about his famed works there?

Yes, they still draw our attention despite the changes to the surroundings. When they were made there were fewer buildings and they should have stood out more prominently.

If you follow them chronologically they also mark the trajectory of his growth as an artist and of the changes taking place around him. Sujata the first work grows out of the earth like a slender tree. Now hemmed by buildings and lost among large trees, she once stood majestically alone beside a single sapling in an open and unbuilt space. His next works were the reliefs on Shyamli the mud house Rabindranath got built for himself. The Santhals enter his creative work through them and they flank its entrance like chthonic dwarapalakas, almost anticipating his Yaksha and Yakshi at the entrance to the Reserve Bank building in Delhi. In the Santhal Family done shortly after that, the marginalized tribal peasant is given a monumental presence which was so far reserved for the rulers. This triumphant entry of the subaltern into Indian art coincided with their emergence in our collective political and social consciousness. His next work is composite of man, birds, and trees interlocked into a single abstract form of great vitality. This was followed by the Thresher, done during the Great Famine years. Towering yet almost headless, she represents the peasant tragically caught between reality and abstraction. He would later call this his unknown political prisoner. And finally, Mill Call his last major monumental work on the campus, coming twenty years after Sujata, it represents the triumphant, boisterous march of the tribal peasant turned into mill working proletariat.

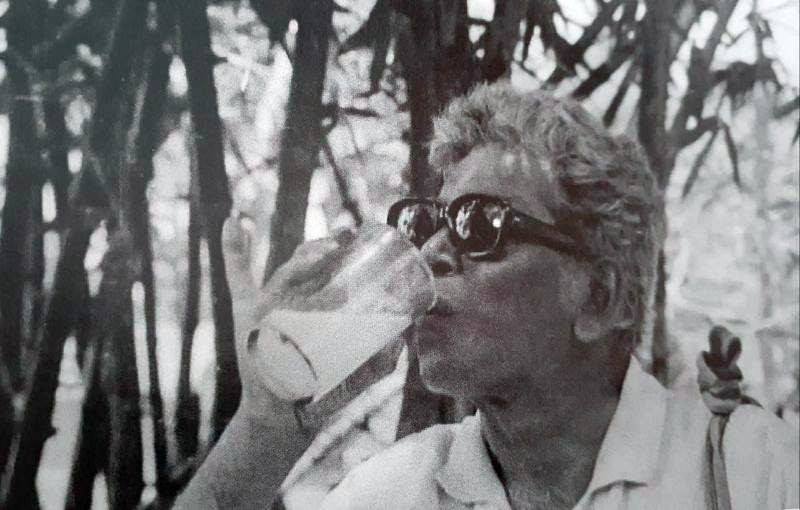

Photographer: Jyoti Bhatt

Photograph courtesy: Asia Art Archive

When placed in a chronological order they form a passage from the lyrical, to the real, to the epic, to the vital, to anguished dissent, culminating in a rhetorical assertion. That tells us something about Ramkinkar, and a certain aspect of our recent history as no other artist has done.

As a teacher in the early years of Kala Bhavan, what was Ramkinkar’s contribution?

His most important contribution was the introduction of sculpture in Kala Bhavana. Until Ramkinkar came onto the scene sculpture in India was an extension of colonial practice. By drawing on both indigenous traditions and modern Western innovations, he changed that singlehandedly and very quickly.

The pedagogic framework that already existed in Kala Bhavana helped him to do this, yet it was a momentous achievement and a turning point in modern Indian sculpture. As a teacher, he did not articulate his views as eloquently as Benodebehari or codify them as systematically as Nandalal. He communicated it to his students more by example and aphoristic comments but sensitive students noticed a coherent contour of ideas behind them.

The watercolours and oils of Ramkinkar are the less focused upon areas of his work. What were the influences on this aspect of his work?

It is true that he is more often talked about as a sculptor because of his pioneering status in that area, but his paintings, especially in oils, are also discussed alongside. As in other modern artists who practiced both, Matisse and Picasso for instance, a dialogue between sculpture and painting was integral to his artistic development.

However, his watercolours have not received the attention they deserve. Perhaps this is due to our habit of looking at watercolour as a minor medium. While his sculptures and oil paintings began with visual facts and moved away from them, his watercolours which were painted on location and executed quickly allowed for a spontaneous coalition of sensibility and sensory experience.

Photograph courtesy: National Gallery of Modern Art

In his oil paintings we notice stylistic affinities with Western several artists and movements— especially, Cezanne, Picasso, Cubism, Futurism, Expressionism. But he uses them like different inflexions of the same language. In the watercolours his approach is more unique. And in them, we notice an affinity with Nandalal and Benodebehari and East Asian calligraphic painting.

Ramkinkar comes from humble rural beginnings; did that add a sense of the real, a feel of the earth itself rising to sculpt itself in his works?

Yes and no. Origins are important but we are also shaped by our aspirations, choices, environment, and associations, so tracing everything back to origins can be sometimes misleading. In the case of Ramkinkar his humble origin is often overstressed to the detriment of obscuring his intellectual interests which were closer to that of a cosmopolitan modernist. He empathized with the Santhals, admired their natural dignity, uprightness, and industry. But from the chronology of his sculptures we briefly sketched, it is clear that his perception of them was not static but evolving. I wonder why he should carry the burden of his origins more than others.

Today as public installations have become a talking point with new dispensations in states and the centre reimagining a cultural footprint, what can we learn from the public artworks of Ramkinkar? How do we keep art separate and independent of political narratives and agendas?

Yes, an attempt to reimagine official public art is on. But this is not entirely new; the use of art to legitimize the views of those in power has a long though chequered history. We are merely seeing a particularly concerted effort now.

Now, about Ramkinkar. His sculptures in Santiniketan were not commissioned. They are his personal expressions placed in public spaces, shared with the community he lived in. The only exception was his work for the Reserve Bank; more than an opportunity it proved to be a torment. It went against his idea of art as a freewheeling exploration or adventure and drained him mentally and physically. His experience with the monument to Netaji was not different but thankfully his proposal was rejected at the very outset. So it saved him the trauma of dealing with officialdom.

This, however, is not to say that there cannot be good public art. A lot of the art we admire was conceived and commissioned as public projects. We have had artists who wilfully served tyrannical, autocratic, and totalitarian regimes, but also those who resisted or subverted their wishes. So art need not become apolitical; artists need to engage with their times according to their inner convictions. We can only hope that their convictions will be partisan to our common humanity.