The first film by Satyajit Ray that I saw, soon after its release in 1959, was Apur Sansar. I was still a child, then living in a far-off European city, and the film screening had probably been organized by the Indian Embassy there. My parents must have taken us children along to the viewing because we could not be left alone at home. But I was profoundly affected by the film, and have never forgotten that experience of watching what was, even for a child who had very little exposure to cinema, unmistakably a masterpiece. In memory, certain aspects of this experience coalesce to produce a distinctive context for my response: the alienating location, a large, dark hall in an unfamiliar public building with formally-dressed strangers speaking in foreign tongues, the immersiveness of the screen-world for a child who could then speak and think only in Bengali, and the film’s deliberate visual contrast of the sunlit Bengal countryside with the dark and grimy city, unknown to me, yet so recognizable across the gulf of time and space that individual scenes seem imprinted upon my mind. Sixty years on, I am never sure how much I recall from that first encounter and how much has been superimposed by so many subsequent viewings of the film. Yet the fact that I have never let go of that defining, early memory of viewing Apur Sansar has a fundamental connection with my understanding of Satyajit Ray’s cinema, and its location at home and in the world.

For Indian cinema, Ray has served as the iconic example of cosmopolitan modernity, a film-maker owing little or nothing to his predecessors in the Indian film industry and almost everything to Western art directors like De Sica, Renoir, Ford, Wilder, Flaherty, Lubitsch, Truffaut, even Godard, whose work he studied closely and acknowledged, drawing upon them to transform the language of Indian cinema. In his youth, by his own admission, he watched Western films, followed the great masters as well as Hollywood, read mainly English light fiction, and developed an enduring passion for Western classical music. When, in 1944, Dilip Kumar Gupta of Signet Press asked him to design and illustrate an edition of Aam Antir Bhenpu, a children’s re-telling of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s Pather Panchali, he had not read the novel. But it left a deep impression on him, though the first film-script he wrote was for Tagore’s Ghare-Baire, and he initially worked on creating scripts from contemporary short fiction like Manik Bandyopadhyay’s ‘Bilamson’ (1943) and Subodh Ghosh’s ‘Fossil’ (1940). There is no doubt, however, as Rushati Sen has demonstrated in her thoughtful and illuminating Satyajiter Bibhutibhushan, that Satyajit Ray owed a primary debt to Bibhutibhushan for the ‘humanism, lyricism, and ring of truth’ that he found in Pather Panchali and transported into the film medium that he made his own. In a recent article, Chandak Sengoopta argues convincingly that Bibhutibhushan’s textual practice was also his primary model for the mobilization of vivid and telling detail, as for natural, unforced dialogue. Ray himself acknowledged that the apparent plotlessness for which Bibhutibhushan had been criticized proved a strength rather than a disadvantage: ‘the pictorial and documentary aspects’ of the Apu trilogy ‘have both been directly derived from Bibhutibhushan and from no one else.’ Even the much-discussed debt to Bicycle Thieves is swept aside by the categorical statement that ‘the true basis of the film style of Pather Panchali is not neorealist cinema or any other school of cinema or even any individual work of cinema but the novel of Bibhutibhushan itself.’ It is as rare for a director to give such credit to a literary work as it is for that literary work to be transformed to pure cinematic experience. Ray has himself written about the technical, collaborative, intellectual, imaginative, and even accidental means of that transformation. He went on, as we all know, to use other writers as well, and to invent — on occasion — his own scripts.

In 1982, looking back at his achievement in cinema, Ray wrote an essay for Sight and Sound called ‘Under Western Eyes’ in which he reflected upon the relation of Indian films with the world, and particularly with the western world. In many ways this essay is uncomfortable reading, showing up the limitations of his own cosmopolitanism. Ray is harsh in his judgment of Indian films, and may appear unduly respectful of ‘the standards of the West’, which, he felt, would be applied to Pather Panchali when it was screened without subtitles at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, at the invitation of Monroe Wheeler. At the same time, he asks, ‘Why should a Western audience care for a downbeat tale of poverty in a remote Indian village? In the total absence of familiarity — with the people, the place, the problems, the language — how could the audience be involved? And without involvement, how could the film work?’ Rather surprisingly, he then launches into a critique, several pages long, of the exoticization of Indian material (or Orientalism, as Edward Said would have called it) in standard British depictions of the subcontinent, revealing an unexpectedly extensive acquaintance with schoolboy stories, sensational fiction, P.G. Wodehouse, Kipling, Forster and Paul Scott, not to speak of ‘the few films about India from the West.’ Even Jean Renoir’s The River, with its ‘placid, poetic approach’, is primarily a story of Britons in India, and fails as a social document. Frankly amazed by the reception accorded to Pather Panchali, which ran for eight months despite a hostile review in the New York Times by Bosley Crowther, who panned it as ‘amateurish’, Ray agrees with Crowther’s assessment of the film’s flaws, but sets out, then, to unpack the secret of its appeal.

It is here that Ray speaks of his departures from the literary as such: the imparting of a structure, founded on contrasted episodes with an element of causality, to the original ‘sprawling saga’; the ‘overlay of details — of speech, behaviour, habits, customs, rituals — which placed the story in a specific time and place within a specific culture’; and the provision of a shared moral ground. Yet although it may seem that Ray is interpreting these choices for a Western viewership, there can be no doubt that — as he says, with some relief, a few paragraphs later — ‘All my films are made with my own Bengali audience in mind.’ This acknowledgement leaves him with a problem that he returns to like a scab that must be picked clean. The density and internal cohesion of his films, their allusiveness, their cultural referents, their slow pace, the hybrid cosmopolitanism of their urban settings, the attribution of a ‘Western’ origin to authorial characteristics like irony, understatement, humour, the use of leitmotifs — all of these are in fact barriers to cultural intelligibility. The Western viewer must work hard to understand a film like Devi, just as the Indian viewer must work to appreciate Aranyer Din Ratri. Both must be contrasted with the ‘unmitigated kitsch’ of a film like Bapu-Ramana’s Telugu mythological epic, Seetha Kalyanam (1976). To confound such a work with Ray’s oeuvre under the heading of Indian cinema is to commit, Ray clearly feels, a ‘category error.’ In that case, how does cinema — or any form of art for that matter —work? Ray’s careful teasing out of the elements in his films that create what we might call conditions of visibility — or intelligibility — is in a way counter-productive. It banalizes and reduces what we see to a number of identifiable components, and suggests — though we know this to be false — that they have been chosen to provide a rudimentary, universally legible, sub-text. Ray himself is clearly aware that this is not the case, and the only way in which he can conclude a somewhat unsatisfactory exercise in cultural translation is to say that ‘true understanding will take time: slighted for so long, India will not yield up her secrets to the West so easily.’

The question that Ray is asking here is an important one for the category of world cinema. Briefly put, it is: ‘In what does aesthetic intelligibility consist?’ On the one hand we have the formal techniques that, Ray feels, belong to the grammar of the medium itself and have largely been developed in the West: on the other hand, we have the cultural constituents that are rooted in specific locales and resist translation, but are integral to film content. Yet, as Ray’s own reliance upon the literary makes clear, he was always aware of the work that translation does, in simultaneously locating and circulating meanings, while dissolving – or making fluid – the notion of medium. Addressing a Western readership in Sight and Sound, seizing the opportunity to vent some of his irritation at missed meanings, Ray was perhaps a little too anxious about how his films were understood. In fact, as he says at the start, Pather Panchali ran for eight months: perhaps it was understood well enough, or perhaps it was able to teach film-goers its language?

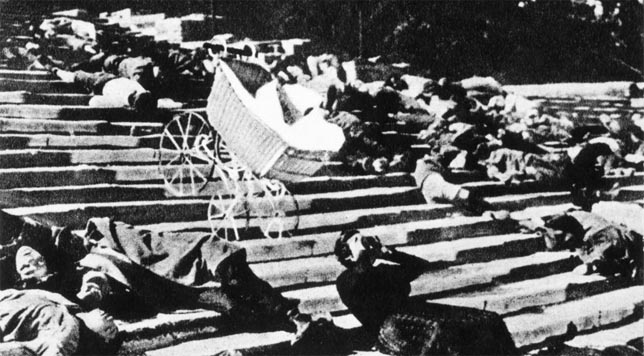

Let me close with another memory, that of viewing Battleship Potemkin as an adolescent in the late 1960s, at a special screening in the New Empire theatre in Kolkata. I think it was Ray himself, on one of his visits to our house, who had told me to go: my father was a friend and lifelong admirer, resigned to criticism and occasional mockery on this account from leftists in his circle like the poet Samar Sen. Ray was seated behind me in the cinema hall though he had already watched the film some twenty times: it was the first film to be screened at the Calcutta Film Society that he founded in 1947. The print quality was poor and there were the usual hitches. I remember Ray’s deep voice in the darkness calling out ‘Sound!’ when, as common in those days, a temporary equipment failure turned off the background music. He must have known Edmund Meisel’s original score by heart, and following Eisenstein’s recommendation that the score be rewritten every twenty years, had himself composed a background score for the film from his collection of Western classical music (which of course was never used).

That too was an unforgettable experience — not my first exposure to world cinema but certainly an encounter with greatness: the Odessa steps sequence is also imprinted on my mind from this occasion. The situation was the reverse to the one with which I began: we were in Kolkata, the hot, chaotic, politically turbulent, even violent city that we knew as home, sitting in rickety seats in the decrepit glamour of the New Empire theatre to watch one of the acknowledged classics of world cinema, a silent film from 1925 on the Russian Revolution — an event about which my knowledge was confined to my school history book. Yet the recognition, the sense of acknowledgement, the wonder and imaginative absorption ran parallel to what I had experienced all those years ago when I first saw Apur Sansar, although their material was so different. Ray never emulated Eisenstein in his cinema apart from his use of montage, but he regarded Potemkin as one of the greatest films of all time, and never missed an opportunity to watch it. For me, the reciprocity of these two instances — the Bengali film in a European theatre, the European film in a Bengali theatre — made sense of many questions surrounding cosmopolitanism, cultural specificity, cinema as a medium, and how art can address audiences not even imagined in its making. These were questions that Ray himself had addressed throughout his life and career.