R. Siva Kumar is an eminent art historian and researcher and one of the most prominent critics of contemporary art in India. On Somnath Hore’s birth centenary, he speaks to Daakbangla.COM on the creative universe of the force of nature that was Hore, his rooted-to-reality ideology, his relevance in modern-day practices and his stature as both artist and deeply revered teacher. In conversation with Malavika Banerjee.

Somnath Hore’s body of work is synonymous with the Bengal Famine. Would you agree that the impact and reverberations of that event stayed with him throughout his creative life?

Yes, that is true. The experience of the Bengal Famine was a defining moment in Somnath Hore’s life, and it continued to haunt his consciousness and his art until the very end. Very rarely do we come across an artist so focused, almost obsessed, with a single experience from one’s early life. But it also needs to be pointed out that he did not focus on the event itself but on the perspective on life it gave him, on the inhumanity built into our social and political structure that caused it and will continue to cause similar catastrophes. Besides the pain he experienced at the time it is also this perspective and the mixed emotion of hurt and anger it aroused in him that runs through or, as you rightly put it, reverberates through his art.

To look at it from another perspective, does Hore’s engagement with the Famine and Tebhaga sometimes distract from his formidable expertise and innovation as a printmaker? How would you assess his contribution to this field?

No, I don’t think that is true. On the contrary it compelled him to be innovative. He was too astute an artist to make that mistake. We should remember that he was not a neurotic expressionist stuck with one theme but an ideologically committed artist. He realized very early on that emotions however strong will jade and it is not enough to hold the viewer’s attention over a period of time. Even to keep the emotion alive within himself he had to face it as a new representational challenge again and again. This made him innovative, and exploring different mediums was a part of that process.

We can look at his contribution from two perspectives, as an artist and as a teacher. On both counts he stands out. He explored the entire gamut to mediums and techniques available to a printmaker and added at least one of his own, paper-pulp printing, which is in some respects a bridge between print making and relief sculpture. As a teacher too his impact has been exemplary, he has probably nurtured more printmakers than any of his contemporaries.

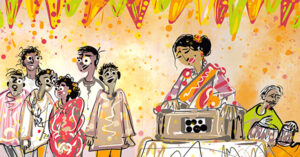

Image courtesy Galerie 88

Hore’s time in Santiniketan coincided with a rich time of creativity at Kala Bhavan, with Ramkinkar Baij and K.G. Subramaniyan. How did these artists collaborate and feed off that special period?

He joined Santiniketan as a teacher in 1967, but his association with its artists goes back to the early 50s. Despite his ideological commitments he soon realized that socialist realism had grave limitations and artists like Nandalal, and Benodebehari were exploring the possibilities in printmaking from a modernist perspective that was more rewarding. I presume it was this that drew his attention to Santiniketan in the first place.

But his decision to join the faculty and move to Santiniketan came under a different circumstance. By early 1967 he was disenchanted with the art world in Delhi and resigned from his job at the Delhi College of Art. Geographically Santiniketan belonged to the periphery of the modern art world but it had a central place in the discourse of modern art in India. Benodebehari and Ramkinkar were still there and they were living exemplars of the kind of artist he wanted to now become, deeply committed to one’s vision of art and life and yet detached from the bustle of galleries and detached from art trade. Some years later Subramanyan also returned to Santiniketan. He too was an artist committed to a larger vision of art and life. Though ideologically they had different moorings they recognized each other as fellow travelers with whom they shared a great deal, especially the vision of art as vocation.

The Wound series, acclaimed as it is, is now a much-sought after period from Hore’s art. Hore was famously reclusive and honest to his political beliefs. How did he manage to keep the political core that informed his art even though he was ardently chased by galleries and art dealers?

His had a rather patchy and uneasy relation with galleries. Between 1956 and 1968 he had as many as eight solo exhibitions with in a period of 12 years. During this period he also won the national award thrice. So in a sense he was in the thick of things but, as I have already suggested, he felt that this was in conflict his ideological commitments and his view of art. As a Marxist he felt that the gallery system was in conflict with his ideological commitments, so becoming a recluse was a necessary strategy for him. It also helped him to be innovative without being overly concerned about how his work would be received by professional critics and the art market. He was skeptical about the role of galleries as a part of the market system but no artist can remain without an audience and in the modern period it is the galleries that facilitate this meeting of the artist and his audience. Though his relationship with the art world was fraught with anxiety, coaxed by admirers he opened up a little more to the idea of showing his works after 1990.

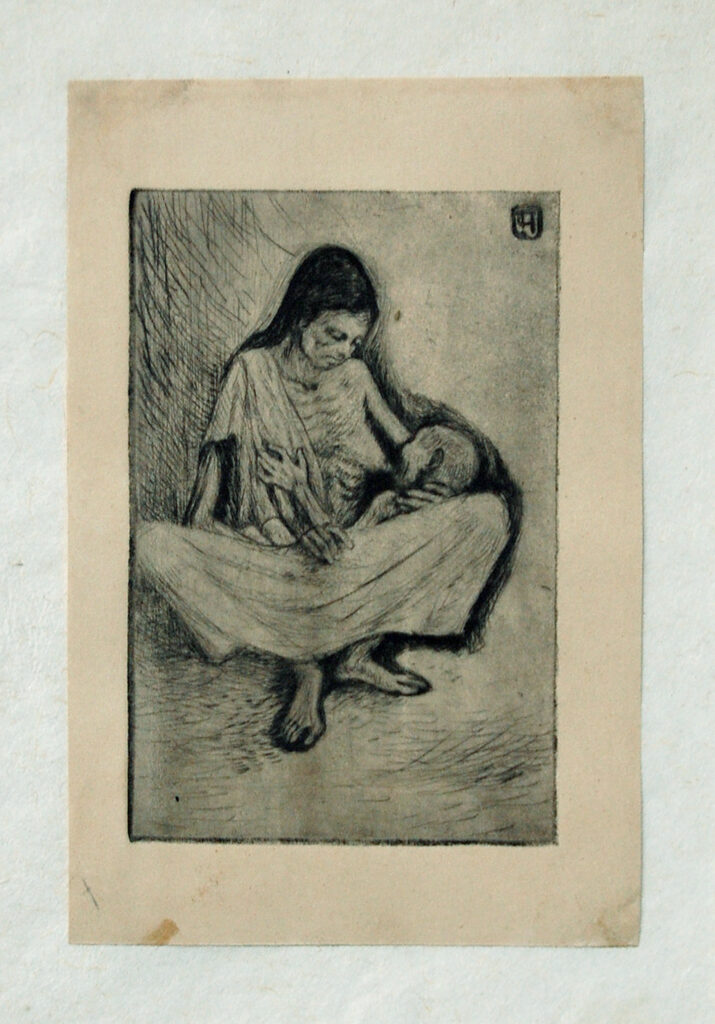

Image courtesy Galerie 88

Hore’s sculptures, haunting in their gaunt and sunken-eyed starkness, spoke of the human condition but also were masterfully created. Today, his sculptures are feted the world over. How do you assess some of his prominent sculptures?

By the mid-60s the element of touch was on the up in his prints. In his intaglio prints the surface was becoming more tactile; this led to his pulp-prints which were like relief sculptures. The initial work for these were done either on clay tablets or on wax sheets which were then cast in cement and turned into matrices for the pulp-prints. The first sculptures were made using these wax sheets, by cutting them up and manipulating them with his fingers and turning them into forms that were then cast in bronze. His sculptures mark the culmination of his urge to preserve the materiality and the process in the final work. In a strange way it also allowed him to go back to the violently abused body of the famine victims. Wax sheets that folded like skin, and preserved the jabs and cuts inflicted on it like the human body and bronze that gave it permanence allowed him to bring back to life those remembered images with an astounding palpability and sensuousness that drawing and printing did not allow. Besides the physicality of his sculptures their small size which fitted into the human hand made it ideal to be understood through touch and feeling. They render human suffering and fragility with great intimacy and sensitivity.

As someone who interacted with Hore, what is your abiding memory of the man and the artist at work?

He was passionate about everything be it his convictions or the work he did. He tried to cover it with a veneer of reason but was not always successful. One always felt an element of restlessness behind the surface and there was always enough cause to be agitated about. Given the ideological position he took, empathy for the underdog was imperative and he never failed in expressing it. As a teacher he was very generous with his knowledge and could recognize talent when he saw it, and appreciate it even when there was no ideological convergence. Finally as a printmaker and as a tireless experimenter he did all his work in the common studio and to see him progress from idea to the final print, print after print was a great education for his students. It is this image of the ever engrossed artist working alongside the students in the studio that I cherish most.

Finally, it is rather ironic that Hore’s centenary coincides with an election that is polarized and antithetical to Hore’s worldview and politics. What are the centenary plans at Visva Bharati and other parts of Bengal?

He would have been very disturbed by what is happening around us now. Although he had given up his party membership way back in 1956 his instincts remained entirely socialist with deep subaltern sympathies. Polarization and instrumenatlization of people would have been against his mental ethos and made him very unhappy.

Although we are still in the midst of the pandemic my colleagues at Kala Bhavana are planning a few small events including an exhibition and other events to mark the occasion. I also understand that a major book on him is under preparation edited by the sculptor K. S. Radhakrishnan and funded by the Takshila Foundation. A book on him documenting his very rich and diverse career was long due, but it did not happened partly due to his own reticence. It is good that it is happening though the centenary year is a little late in the day for an artist of his standing. And I am sure there will many more events, exhibitions and publications to mark the occasion.