Five hundred years ago, when the Mughals ruled north India, there was an explosion of Bhakti poetry across India. From north to south, people expressed their devotion to different forms of god using emotionally charged language. One of these forms of God was that of Krishna.

The songs dedicated to Krishna are composed in local languages. They are connected to particular temples where Krishna is known by different names. This makes the songs unique. So, although we speak of Krishna Bhakti as a pan Indian phenomena, the reality is he has many local manifestations. People from one part of India may not recognise Krishna from other parts of India until they observe certain details.

For example, in Rajasthan, Krishna is called ‘Shrinathji’. He is visualised as holding the Govardhan Mountain on his finger, his eyes are boat shaped. But in Odisha, Krishna is called Jagannatha. The image of Krishna is an incomplete wooden statue, which is replaced every 12 years or so. It has characteristic round eyes. Shrinathji is worshipped alone. Jagannath is worshipped with his brother, Balarama, and his sister, Subhadra. People from Rajasthan visiting Jagannatha Puri may be familiar with Krishna. But they may find the images and the name of Jagannath very different from the image at the worship of Shrinathji at Nathdwara.

In Gujarat, Krishna is known as Dwarkadheesh, or the Lord of Dwaraka. But the image here shows him with four arms or Chaturbhuj, more like Vishnu, and less like Krishna. The images of Dwarkadheesh are found in Dwarka, as well as Dakor. In Bengal, Krishna is called Keshto in the Baul traditions.

‘…Although we speak of Krishna Bhakti as a pan Indian phenomena, the reality is he has many local manifestations. People from one part of India may not recognise Krishna from other parts of India until they observe certain details.

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu made his image as Murlidhar or the flute-holding Krishna standing entwined with Radha. This image is found in the Gaudiya Vaishnava Parampara. In the Shankardev traditions of Assam, in the satras of Assam, Krishna is popularly known as Madhava, linking him with madhu or honey. However, in Namghar, where his name is chanted and stories narrated, there is no statue of Krishna.

If you read old Tamil literature, we come across a cowherd god called Mayon. Mayon is surrounded by milkmaids and has a beloved name called Nappinnai. We wonder who he is. A closer examination reveals he is Kanha of Hindi literature, and Nappinnai is Radha. This is the same god, referred to very differently in the northern belt and in the southern regions.

In Karnataka, Krishna is worshipped as Chennakeshava or the little Krishna. His image shows him holding a churning rod in one hand. In Kerala, he is visualised as Guruvayur. Guruvayur means the deity who was worshipped by Brihaspati and Vayu, the planet Jupiter and the wind-god. It is said that this image was worshipped once by Devaki and was passed on to the kings of Kerala, a long time ago.

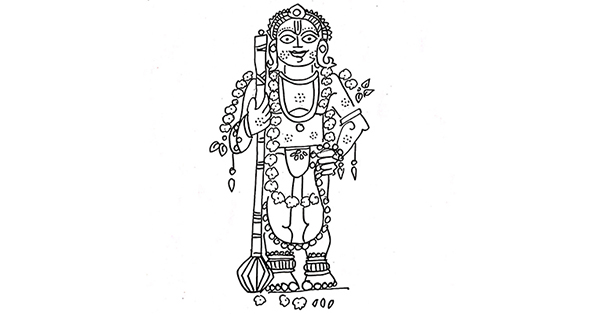

In Maharashtra, Krishna is worshipped as Vithala, in Pandharpur with Rakhumani or Rukhmani. Krishna here stands on a brick with arms akimbo. The word Vithoba is connected to Vishnu, or Vithu, in the old form of Marathi.

In Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, the deity looks like the four armed Vishnu but is addressed as Govinda, or Gopala, the cowherd. In Chennai, there is a rare temple where he is called Parthasarathy or the charioteer of Arjuna. This statue is gigantic and has a moustache, a very unique feature not found in other parts of India. In his hand, he holds not a flute but a conch-shell. In the Guru Granth Sahib of the Sikhs, there is repeated reference to Hari and Madhusudan, names of Krishna.

Thus, we find Krishna visualised differently in different parts of India. Thus the concept of unity and diversity finds a mythological expression. Diverse regional forms of Krishna are united by the Puranic idea of Krishna, the eighth avatar of Vishnu.