Telebhaja

What is telebhaja? Tricky one, that. Could any battered, breaded and deep-fried fritter be classified specifically as telebhaja? No, the true-blue Bangali will protest. There are many deep-fried fritter variants in ‘Bengali’ cuisine that do not classify as telebhaja, sold on the streetside, a quick-fix snack (Kumroful-er bora; batter-fried pumpkin flowers, for example). On the other hand, most telebhaja cannot be a part of a proper square meal, especially lunch or dinner (Alur chop or phuluri for dinner? Ghastly thought!). Then again, this can vary from region to region in the Great Indian East, and it certainly is a fine line that must be treaded cautiously.

I love telebhaja. There was a time when my evening snack would invariably consist of telebhaja or jhalmuri; often both, sometimes together, with a handful of green chillies. To get back to my roots, per se, I put in a few kilometers, on foot and otherwise, through the city and beyond, and went through an absolutely unsupervised, unprescribed (or was it unhinged?) binge of telebhaja for a couple of weeks. I came to two solid conclusions. One, telebhaja must be battered with besan. Two, telebhaja must be fried in what seems to be a semblance of mustard oil, sorsher tel. The current avatars are all mass fried in an oil that gives off the aroma of the mustard variant for the first couple of minutes and then morphs into some piping hot liquid without any traceable family history. So be it, but definitely, definitely, no other kind of cooking medium.

Back to the big question, then. All chop is telebhaja in the technical sense of being a deep-fried dish; but telebhaja isn’t synonymous with, and sometimes may not include, what we understand as the Bangali ‘chop’. If it’s a bora, yes; not if it is a chop – even though the latter deep-fried. And battered, please – breaded, it becomes chop, though alur chop is batter-fried and is thus technically a misnomer.

Broadly speaking, what we understand as telebhaja includes the Big Four: alur chop, beguni, pneyaaji and phuluri. Any telebhaja stall worth its salt has to serve these four items, and may include many other varieties, just because they can. Thus, dhonepataa’r bora, capsicum chop, longka’r bora, tomato’r chop, and the rare but exquisite if made right polta’r bora are all part of the Bangali fritter multiverse. Laxminarayan Shaw’s iconic store near Scottish Church School on Bidhan Sarani is as well-known for its chops as its dhoka barfi; this stuff is brought both to be eaten on the spot and taken back home for a dalna the next day. Despite being called chop or bora, telebhaja should not include fish or meat ingredient-filled fritters, and will strictly be battered, not breaded, as pointed out. And even if these are battered and deep-fried, the vada in vada pav or the alu vada in any Udipi outlet isn’t telebhaja. It is strictly a question of taste.

Telebhaja is all hand-made; the entire process is touch-based, from prepping the batter to letting the flattened circles or mounds slide into piping hot oil. Logically, any Brahmin sensitive to the rules of untouchability would have hardly risked a ganga snaan following a tasty evening snack from a chnaral’s telebhaja spread. Thus, the popularity of telebhaja, as widespread as it is today, could have only coincided with a time when people stopped bothering about the chhyut-acchhyut barriers any more.

Move away from Kolkata, and telebhaja changes taste, shape and recipe. In Mecheda in Midnapore, the alur chop comes with a healthy mix of cubed coconut, and is sold as narkel-alur chop. On Hill Cart Road in Siliguri and the cart-drawn mini-store on University Road near Vishwa Bharati, Santiniketan, right outside the post-office, telebhaja is often sold with kasundi; because the shops also offer dim-er devil and varied meat, fish vegetable chops in the breaded avatar (Kalika on Surya Sen Street offers the kasundi as well). In Malda town, the kasundi turns to aam kasundi, come summer, coupled with flavourful, hot pneyaaji the size of one’s palm.

Speaking of history, what is the origin of telebhaja? There is none; it has never been documented, never been researched to be documented, never finds more than a passing mention in literature to be taken up as a subject of research, even. But food, we know, is intrinsically linked to both the socio-cultural history and the economic antiquity of a city and its people; more so, peoples’ food, streetside, cheap food. In other words, vendor snacks like telebhaja.

History does mention historic figures like Swami Vivekananda and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and their fondness for telebhaja. Laxminarayan Shaw’s store, established in 1918, touts Bose’s preference for its telebhaja as almost the sole selling point. Vivekananda, a self-proclaimed foodie, had a weak point for nicotine, tea, ice-cream – and beguni.

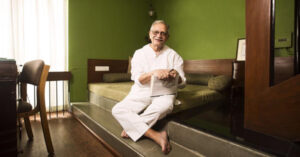

But how did the deep-fried battered fritter family take hold, spread and flourish as a public choice in early 20th century Kolkata, still grappling with caste and untouchability, vegetarian diets and the baggage of sin and virtue? Amitabha Malakar, artist, foodie, writer, racounteur, theorises that the rise of telebhaja must have taken shape “while the iron rules of the caste system were gradually but surely being slackened”. Telebhaja is all hand-made; the entire process is touch-based, from prepping the batter to letting the flattened circles or mounds slide into piping hot oil. Logically, any Brahmin sensitive to the rules of untouchability would have hardly risked a ganga snaan following a tasty evening snack from a chnaral’s telebhaja spread. Thus, the popularity of telebhaja, as widespread as it is today, could have only coincided with a time when people stopped bothering about the chhyut-acchhyut barriers any more.

The tenets of caste tie in with food habits, and this, too, is where interesting changes could have taken place. Not streetside, footpath vendors perhaps, but a number of shops in town still offer ‘only vegetarian’ telebhaja i.e. sans any onion and garlic, pneyaj-rasun (Rokkhakali Niramish Telebhaja, bang opposite the Laxmi Narayan Shaw store, is a prime example). The inclusion of the pneyaaji in telebhaja fare is a testament to how changing habits in cuisine reflected on a popular snack.

Malakar points out another intriguing fact via the location of century-old telebhaja shops – again, establishments, not temporary vendors – close to either a brothel or liquor bars (Laxmi en route Sonagachi, Kalika en route Harkata Goli, anonymous little Rashbehari Avenue stores en route the brothels that line the banks of the Buri Ganga in Kalighat). “The introduction of peyaanj-rasun in telebhaja may well have been a well-thought of move for the bhadralok on his way home to the wife after a drink and a romp, suppressing unholy fragrances of all kind,” he says.

Gender has had an interesting role to play in the telebhaja tale of the city. Most of the telebhaja shops in the northern end of town, pedigreed stores, so to speak; are run by migrants from Odisha who settled in the city over a hundred years back. In these establishments, men prepare, fry, serve telebhaja, and manage accounts. No ladies are involved in the entire machinery – an exclusion possibly originating in the draconian system of keeping women and the natural process of their menstruation at bay.

On the southern fringes, on the sidewalks of Gariahat, Rashbehari, Behala, Jadavpur, Kasba, Garia, Sonarpur, and the more recent mini-town of Bidhannagar, solo women rule the telebhaja vendor market. Even in the case of telebhaja-seller couples, it is women who put in the muscle, while men are relegated to handing out the goods and accounting. Some vouch that Mashi’r heath-er beguni or phuluri just tastes superior, and there is definitely a ring to the phrase. Along the sidewalks to hallowed country liquor bars like Barduari and Khalasitola in central Kolkata, the seedy Buri Ganga khaal paar in Tollygunge and Kalighat, in Garcha and in Bondel Road, telebhaja finds pride of place in the snack spread to go with a bottle, deep-fried and sold off in a jiffy by one mashi or another. And then of course, there is sandhyabajarer telebhaja – telebhaja bought and sold in the temporary markets that sprout every evening along one station or another, in Ballygunge, Jadavpur, Bagha Jatin, Dum Dum. The telebhaja at this bajaar – the budget version of the morning fare – is similarly to be made with the chnaat sabji, the remnants of the day. Connoisseurs, including Malakar, vouch for the “different” taste of the telebhaja thus made.

In the telebhaja universe, what intrigues me is the total anonymity that has come to be the hallmark of the maker. You tend to know your favourite phuchkawallah by name. Not your telebhaja vendor; despite the pandemic, hundreds of telebhaja sellers still sit by Kolkata footpaths every evening, even now. We know of one Kalika, a Mouchak, one Laxmi Shaw. The rest of the 997 remain nameless; ‘Dada’, ‘Kaka’ or ‘Mashi’, at best. There is a possible explanation for this — unless you are over-fastidious, you don’t eat telebhaja from one, specific, single vendor. People that tend to regularly consume telebhaja tend to walk about the city, usually a lot – and get their telebhaja fill from different places; if not many, at least three or four. And that class of people can range from the rickshawallah to medical representatives, from dish-antennae repair workers to office executives, from thinkers and artists to fitness fanatics indulging in a cheat day.

Of course, most streetside snack is sold by such anonymous vendors, but it is curious to romanticise this anonymity in the context of telebhaja. In my mind, it serves as a metaphor of the anonymity of existence in a metropolis, any metropolis. Sometimes, when the threats of familiarity, social norms, structure and this city life, get almost too oppressive to bear, it is beautiful to munch on an anonymous pneyaaji, sold by an anonymous maker and served in yesterday’s newspaper and stand and stare at the Maidan. The roles crumble away, like the fried batter, beautifully.

Photographs by the author