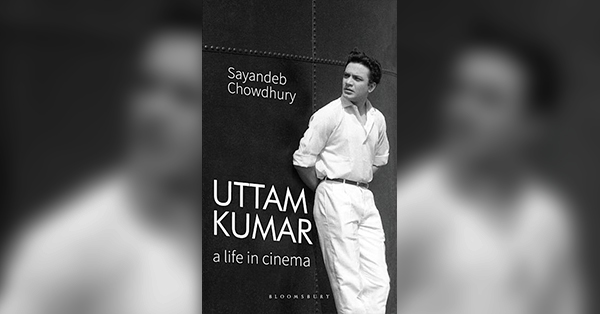

Uttam Kumar: A Life in Cinema is academician Sayandeb Chowdhury’s debut book; a work that he describes as an ‘informed piece of non-fiction’. In truth, the book offers more. As far from a biography of the man as can be, this is, in fact, a deeply-researched work on the mercurial superstar, a lone figure in the history of Bengali cinema, with brilliant insight into Uttam Kumar’s cinematic scope and language. It is also perhaps a singular piece of work that threads together the context of Bengal’s pre and post-Partition history and the rise of the Atlas-like figure of the Mahanayak, a myth that arose out of a certain necessity, at a certain point in time, in service of the Bengali film industry. Here’s Sayandeb, in conversation.

What was the primary impetus behind writing a book on Uttam Kumar, especially at this point in time and in context to Bengali cinema?

The primary impetus, of course, was the fact that there is no book on Uttam Kumar, which takes into account the whole of Uttam Kumar’s cinematic body of work, but also puts in context Uttam Kumar’s cinema within a broader social-cultural context of Bengal, both pre and post-Partition. The book goes back to the beginning of cinema in Bengal, then comes to Partition and after, and how some of the conditions came together to create a kind of a need for a specific stardom to come into play. I thought two things were missing: one, a generous and a general assessment of Uttam Kumar’s entire cinematic life and two, placing him within a context.

Why now? It has been about 40 years since Uttam’s death, and there is hardly any diminution in his aura and charm. Four decades is a long time to measure why and how Uttam Kumar mattered, in a certain way, both historically and in retrospect, to Bengali cinema.

This is your debut publication; how and why did you think of a comprehensive volume on Uttam Kumar, in English, as your first book?

I never really intended to be an author. It was just that a subject like Uttam Kumar has been with me for a long time. I, like many in my generation, grew up watching his movies on television, and was impressed and awed, in turn, by the things I saw on screen. Uttam’s cinema, the past of Bangla cinema that you saw on television, and the kind of things we saw in the Eighties, the distasteful stuff that you saw in cinema halls, the ‘Baba Keno Chakor’ days, presented so glaring a contrast that Uttam, first, was a kind of a surprise that became an intrigue, and over the years, had stayed with me. I realised that something was to be done about my sense of intrigue at Uttam’s persona. Slowly, but surely, the idea of the book emerged.

This is my first book, it is an ambitious subject. Given that Uttam Kumar is still an extremely popular public figure, I had to be very conscious about what I was doing. I couldn’t just write another book on Uttam Kumar; there are a dime a dozen ‘bad’ books on him in Bangla and a meagre amount in English. The book had to be something that would say something new, but at the same time, as a first-time author, I had to be extremely cautious about how I was saying that, the way I was planning the book. I was well aware that I could fail, but I had to try.

Uttam Kumar: A Life in Cinema is not a straightforward biography, neither does it engage in arid critical analysis of his work. How would you describe your book?

This had been one of my major concerns; when the book finally took off, all through 2018 and 2019, not a day went by when I did not think of what the temperament of the book will be. I never wanted to write an academic book. He’s a popular hero, a matinee idol; ‘Guru’, ‘Mahanayak’ and so on, and I never wanted to write an arid, critical analysis of his film language, replete with theory and all of that. At the same time, I am a willy-nilly academic, so I couldn’t just write a biography that was reader-friendly but with no substance, which most cinema writing in India unfortunately becomes.

I don’t know whether I have been successful in taking this middle path in the book. But I had to put in the research, to make it informed, with some kind of insight, so that even those who already have some kind of understanding about Uttam Kumar’s cinema still have something that hasn’t been said before, something to hold on to. The book, I believe, will also not alienate the general reader. I would describe it as informed, researched non-fiction, written for the intelligent reader. It is a book for the general reader as much as the cinephile and the academic.

I think there are many such films, especially from mid-1950s to mid-60s, where he lets his stardom be tested. But the one film where he really, really did this was Nayak. The idea of Nayak, of course, is that the better Uttam plays nayak, the character of Arindam Mukherjee, the more the very idea of Uttam Kumar is in danger, because there is absolutely no confusion that Arindam Mukherjee and Uttam Kumar are one and the same.

‘Mythical matinee idol’—perhaps the most apt epithet in reference to Uttam Kumar’s lasting legacy. Arguably, there are no matinee idols in Bengali cinema, any more. In that regard, what is Uttam Kumar’s relevance, in 2021?

If I want to be flippant, I would say Uttam Kumar is ever-relevant, in the sense that he embodies an entire generation’s aspirations, a cinematic domain. His relevance has never dipped, because in Uttam Kumar resides half the history of Bangla cinema, if the other half resides with Ray & Co..

But the fact that Uttam Kumar is still a matinee idol says two things — one, there was a certain kind of cultural make-up that made his stardom possible. Things came together, in a certain way, under certain conditions, in certain years, for an Uttam Kumar-like figure to evolve. That cannot be replicated, and is thus, impossible, before or after Uttam Kumar. Which is why he’s such a single most important figure, almost ‘mythical’ in that sense. A kind of mythos was necessary to sustain a figure like Uttam Kumar, it could only be embossed on a figure like Uttam Kumar. It is a cycle, so to speak; a certain kind of idolatry was built around the mythos, and the mythos was necessary to sustain that kind of idolatry.

But at the same time, we have not had a better actor, better performer, better star, indeed, a better ambassador of Bengali cinema, a Titanic figure at that. There will never be a condition, or a performer of that caliber, that will give rise to another figure like that. To bring these two genes together — that of a superlative, performative tradition and a superlative stardom —in one particular screen persona, will never happen.

What, in a nutshell, is your explanation of Uttam Kumar’s Atlas-like stardom?

There is a historical conditionality of Uttam’s coming together. There is also a great amount of responsibility that was placed on Uttam Kumar, to become this singular star to hold aloft an industry for three decades. It is quite remarkable that for two-and-a-half of those three decades, he performed that role quite well, whether he liked it or not. He definitely did not like the idea of him being a singular star, he had consistently said that he was ‘a player without an opponent’, and that’s not a good thing for a good actor.

While it was historical conditioning that made Uttam Kumar possible – the Bengali history of cinema, the Bengali history of consumption of cinema, what kind of cinematic protagonist the post-Partition Bengali cinema wanted to emerge – it was Uttam Kumar’s superlative performance, and the coming together of those two rare genes I spoke of, things that cannot be manufactured, that played a role in his stardom.

Unlike other such idols, you argue that Uttam’s ‘marquee stardom’ regularly subverted the typical and expanded cinema here through his very persona, perhaps as much off-screen as on-screen. Do explain…

This is very difficult to explain in a line or two; half of the book is about this (laughs)! Usually, once stardom falls into a pattern, it tends to stay in that pattern; very few people want to get out of their comfort zones, getting into territories where that stardom might be tested. I think Uttam Kumar did it extraordinarily well; probably the only other star to attempt and succeed at this is Kamal Haasan.

Uttam Kumar started this subversion from 1955 onwards, when he had already become a star. By 1956, he was really up there. Immediately, he started to break away from the romance melodramas, or films that would bolster his image, his stardom. It started with films like Morutirtha Hinglaj and Bicharak in 1958-59, and continued to constantly entreat him to roles where he would look less and less heroic, in films like Kaal Tumi Aleya, for example. In that film, for example, he’s a partly wicked, complicated negotiator, a character that does not flinch from getting what he wants, something that the bhadralok star would never really do. But he did it, and that, at the peak of his stardom. Similarly, Shesh Anko, where he plays a murderer.

I think there are many such films, especially from mid-1950s to mid-60s, where he lets his stardom be tested. But the one film where he really, really did this was Nayak. The idea of Nayak, of course, is that the better Uttam plays nayak, the character of Arindam Mukherjee, the more the very idea of Uttam Kumar is in danger, because there is absolutely no confusion that Arindam Mukherjee and Uttam Kumar are one and the same. While Satyajit Ray is deliberately placing this challenge in front of Uttam Kumar, to see how well he rises to it, Uttam does that with absolute brilliance. There is a sort of self-surgery; the better he plays Arindam, chances are, the more Uttam Kumar’s aura will diminish. But that does not happen, Arindam settles into an Uttam-like stardom at the end of the film, and Uttam’s myth is absolutely undaunted, unblemished, by Nayak.

Do you imagine Uttam in any other Ray film, under the ‘scientific and methodical’ director, and if yes, in what role?

Difficult to say. I write in my book on how there was a plan to make Ghare-Baire with Uttam as Sandip, Soumitra as Nikhilesh and Suchitra as Bimala, and that would have been a fantastic film. This was in the mid-1950s that Ray had thought of this cast (for the classic Tagore story), just after Apur Sansar, when he wrote the script as he nurtured a broken bone in his leg post the Aparajito shoot in Benares. The film never materialsed; Uttam, primarily, was foolish in refusing to essay Sandip – early career, dark character being the usual reasons. But that would have been a fantastic film, I am sure; much better than the Ghare-Baire we have!

Other films? I don’t know. Uttam could have found a place in some of his later films, like Pratidwandi, or Jana-Aranya. He could have been given a character like Shailen Mukherjee’s in Charulata. But I also think Ray would have never done it, because Uttam would have stolen the show over Soumitra as Amal, and that wasn’t permissible!

Among other sections, I found ‘A Gallery of Portraits’, where you outline genre definitions and place a clutch of Uttam Kumar films in each, a real joy to read. Such systematic analysis of his oeuvre has never really been attempted. Tell us about the process of your research.

Thank you! I had two things on my mind from the very beginning — one, I wasn’t going to write a conventional biography, and two, I wasn’t going to write a book based on interviews. What I was looking for, the new answers I was looking for – the modernity of his cinema, breakaway films, the difficulty placed on him as a star, the Atlas-like figure which is inevitably not good for a film culture – were really there in his films, not in any interview. I immersed myself in his cinema for the first two decades. Unfortunately, there are many that are lost; great films like Kar Paapey, pre-Uttam, or Daktarbabu, Necklace, Chirokumar Sabha, or Shankarnarayan Bank. These are films from only the 1950s! Only in this country is there orgasmic joy about a superstar like Uttam, yet no efforts are made to restore some of his lost films.

I went back to each of these films, and their reviews, their booklets, what people had to say about them, and made sure I was not missing out on his entire oeuvre, not just the tired and tested Saptapadi and Harano Sur and Deowa-Neowa, the seven or eight films in circulation on television.

So, there were these three aspects. One, I went back to the cinema, and did as much research as possible on the cinema. Two, I was also only on Uttam Kumar the actor-performer-star persona, and not Uttam Kumar the person, what he wore or ate. I am not really keen on understanding him as a man, he was an ordinary man, sometimes, less than ordinary. It is his stardom that interests me. In fact, that fascinating dichotomy, this ordinary man who became an extraordinary star, interests me, not how he liked his prawns. Three, I virtually read up everything that is available on Uttam Kumar.

What are your thoughts on an Uttam Kumar biopic? Who do you think should play him?

Nobody, nobody should play him. Because some things should be left to imagination. If still done, he will be played by the likes of actors who only reveal themselves going from bad to worse. It will be a disaster. It is impossible to portray a star like Uttam Kumar.

2021 happens to be Uttam Kumar’s 95th birth anniversary year. Do you plan another volume on the man and his work on his centenary?

No, it’s too early. There are two things on my mind; one, there have been many suggestions about a Bangla version of this book. I am not sure, but I wouldn’t mind a Bangla translation of this book. I even have a Bangla title for that.

The other idea is to do a sort of an illustrated book on his life, through the lovely posters and photographs that are still available, a life in pictures, like there are volumes on Chaplin and Carrey Grant. Of course, Kaji Anirban and Parimal Roy already have books on similar lines, but those are primarily based on posters. I am not talking about posters, but more, and entire range of visuality that can be brought in to create his life in images. It is a possibility; it has to be done.

Uttam Kumar: A Life in Cinema, Sayandeb Chowdhury

Bloomsbury, Rs 1,299/-