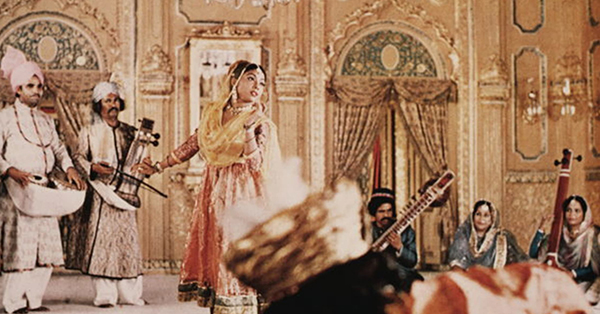

It was a turning point in my life and career in dance,” begins noted Kathak danseuse Saswati Sen, referring to her performance in Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khiladi. She appears in one scene only, set in the court of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, where the Nawab — played memorably by Amjad Khan — is enjoying a kathak performance by a young dancer (Sawati Sen). The scene, says Sen, was a masterpiece, giving audiences in India and abroad a glimpse of the rich Avadhi culture of the time – a culture that the history of the Lucknow gharana of kathak is inextricably tied to.

Saswati-di recalls Dada’s (Satyajit Ray’s) visits to the old Kathak Kendra in Delhi to consult regularly with Pandit Birju Maharaj, the doyen of the Lucknow gharana, whose grandfather and great-grandfather had actually been musicians and performers in the Nawab’s court. Both men would sit in the small room that was Maharaj-ji’s private space in the Kendra, with Ray pressing the dancer for details and anecdotes about Nawabi history handed down through his family. And, of course, he needed dancers who could re-create as authentically as possible the darbar kathak of Awadh. The filmmaker did not wish the choreographer to include anything ‘filmy’, and settled on a slow Bhairavi Thumri – Kanha Mei Tose Hari – for the solo, despite Maharaj-ji’s hesitation about the pace. He said – “Please don’t think that you have to do anything outside your gharana’s style. Please create only what you have heard used to happen at that time.” The result was a lilting piece of choreography and music that Saswati-di says helped convey the Nawab’s state of mind at a pivotal point in the film:

“He (Wajid Ali Shah) is tense, yet he wants some peace through music. So that was the perspective. Dada was not like – daal do, ek gaana daal do! [Just insert a song here]. Not like the films today, where there is no thought about where and why a song is inserted.”

What or who Satyajit Ray wanted, Satyajit Ray got. When trying to identify the right dancer for the solo with Maharaj-ji, Ray remained unsatisfied with the many dancers he saw. He recalled a young student of Maharaj-ji who had performed at a film festival event at Vigyan Bhavan some years before. That was Saswati Sen, who at that point had no thought of becoming a professional dancer. She was studying Anthropology in Delhi University, and was learning dance just for the knowledge of it – nothing further. Her family, too, saw dance as nothing more.

Saswati Sen recounts her first encounter with Satyajit Ray at Kathak Kendra with some hilarity:

“As soon as he saw me, he said – Ei! Tui neche chili na Vigyan Bhavan e? Tui amar cinemay nachbi. (Wasn’t it you who danced at Vigyan Bhavan? You will dance in my film).”

When she agitatedly turned him down saying she could not do it and her family would never agree, he drove home with her immediately:

“My mother opened the door, and almost fainted.

Are you mad? Dada – Satyajit Ray on my doorstep. Why didn’t you call me!

I said – Do you think he gave me any time to think or call!

That was what he was like. He just opened the door and walked in! He was very informal.”

When Saswati-di’s father refused, citing family concerns, Ray asked — “Amra ki baaje kaj kori, amra ki baaje lok? (Do we do anything objectionable, are we bad people?)” The extended family in Delhi and Calcutta ultimately agreed – and Saswati Sen’s life changed.

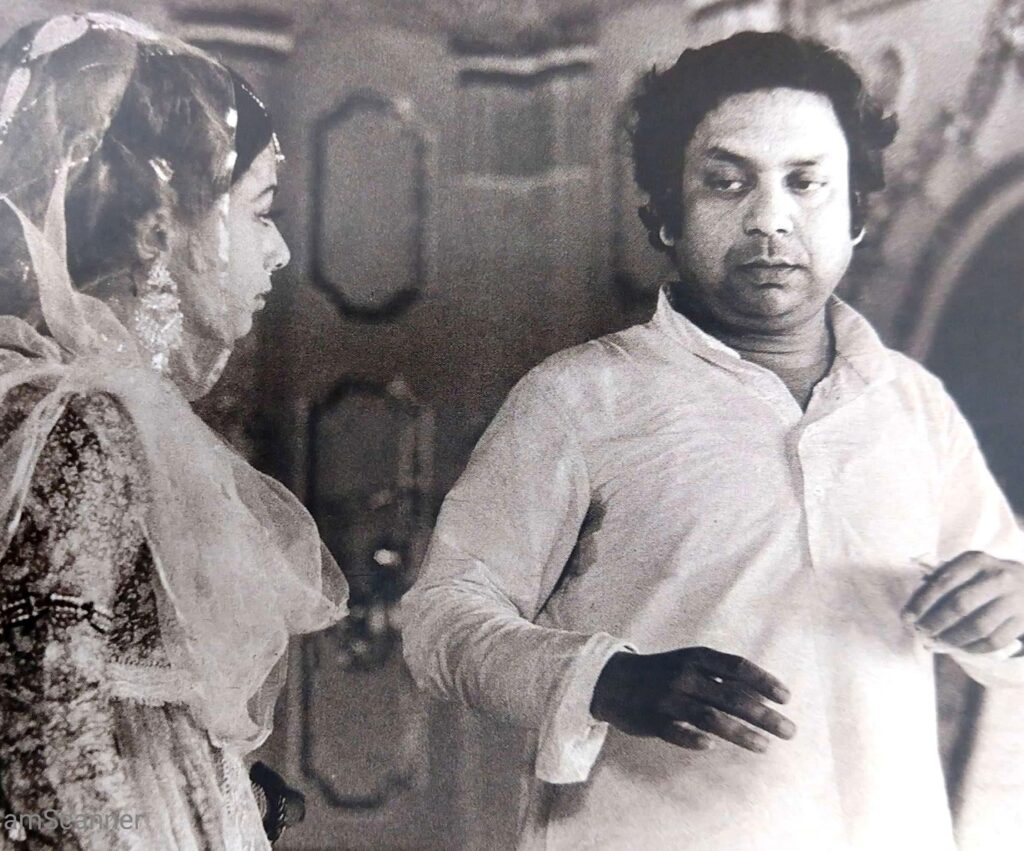

Photograph courtesy: Saswati Sen

She had the unique opportunity to work with two geniuses who were both meticulous perfectionists: Satyajit Ray and Birju Maharaj. And Ray was fully aware of this. During the recording of the thumri at the HMV Studios in Calcutta, Maharaj-ji was singing take after take, always finding some little fault or the other. Ray called Saswati Sen to him, and said:

“Listen, I know how I am. Your guru is the same way. Perfectionist – we are never satisfied with our own work. Toh amar film toh toiri hobe na, jodi tor guru’s shonge kaj korte hoy [So my film will never get made if I’m to work with your guru]. He will never stop. I know, since I am the same. So now when we have a best take, I will give you a signal, and everyone will have to very excitedly say – oh, this was the best! Nothing better can happen.”

And that is how the recording was ultimately finalised!

The kind of training she received from Maharaj-ji to perform this one scene was the training of her lifetime, says Saswati-di. She had already been learning for about 15 years, but those few months gave her a deep sense of the nuanced subtlety of the kathak form that appears so lyrically in the choreography.

“Each angle, each expression, how do I raise the head, set the glance, avert the eyes in shyness, that too in the Muslim darbari style – how subtle should the smile be, how to gently smile and then let it dissolve – all these things I learnt from Maharaj-ji during those 2-3 months.”

Shooting the scene was no less of an experience. She was outfitted in a lavish costume of very fine material designed by Shyama Zaidi, and decked with diamonds, rubies, emeralds and pearls – all from the original Nawabi collection in Metiabruz. Such was the value of the jewellery, that she was accompanied everywhere by two armed guards while on set and in costume. Amjad Khan’s costumes were also sourced from the Nawab’s personal affects, as was the chandelier in the court scenes.

For the dance scene, Ray urged her to think only of performing in a darbar for an audience and not to feel at all nervous because it was a shoot. And every day there was an audience coming to watch the filmmaker create his first Hindi film in colour – Aparna Sen, Soumitra Chatterjee, Utpal Dutt … they were all there.

“Every minute I have learned from these two masters – everything – so sincere, so committed, so passionate about their work. Every little bit in life I have learned from them.”

And then there was the matter of the disappearing cat!

“There was this Siamese cat in Amjad-ji’s lap in my scene – he was caressing it. After two days of shooting, the poor thing must have got very scared. It ran away at night and hid somewhere in the set. And it refused to come out. Anyone who tried, it would slap them or scratch them. So what could we do for the next day – the continuity would be ruined, there were still some shots left, and the cat was supposed to be there. So another cat was brought in, but this was a tomcat – the pair of the other. But as soon as it arrived on set, it started meowing aggressively with all its hackles up. So Amjad-bhai said – Dada, kya laaye hai. Woh ek billa, mein ek billa. Kaise hum dono ka dosti hoga! Who toh billi thi. Phir bhi mere god mein aa gayi. Yeh billa nahi aayega mere paas bilkul. (Dada, what have you brought in? That’s a tomcat, I’m a tomcat – how will there ever be friendship between us! That was a female cat, so she still agreed to come and sit in my lap. This one will never come to me). So how did Dada manipulate it? There were a few long shots left. He got someone to get a bit of furry makhmal material – same colour, same texture as the cat. He made a bundle out of it, and in the long shots that is what Amjad-bhai is caressing with his fingers!”

Ray was insistent that Amjad Khan play the role of Wajid Ali Shah, so much so that he stalled the film completely for a year when the actor met with a near-fatal accident. The role was a far cry from Khan’s reputation for villainous characters in Hindi films. While shooting the short group dance sequence that appears early in the film and features Amjad Khan, the actor said to Maharaj-ji:

“Maharaj! Kaha phansa diya! Bandook-vandook hath mein dete, toh mein karta. Yeh bansuri hath mein, kaise karunga mein! Oh my God! Mujhe toh bara dar lagrahahe. (Maharaj! Where kind of situation have you put me in! If you gave me a gun, that would be better. Instead I have a flute in my hands, how am I going to do anything! Oh my God, I’m really feeling anxious!)”

But Saswati-di recalls him being a gentle, very musical person who would regale them with songs and listen in turn to songs from Maharaj-ji during their breaks on set.

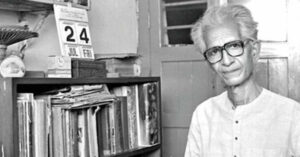

The choice of Amjad Khan for Wajid Ali Shah is emblematic of Ray’s keen eye for actors and characterisation, observes Saswati-di. All the other cast members in the film – Sanjeev Kumar, Saeed Jaffrey, Shabana Azmi, Leela Mishra – were selected with the same meticulous and uncompromising care. And this detailed methodology was to be found in every aspect of his work. Saswati Sen used to often visit Ray’s Bishop Lefroy Road home during the film and later on her visits to Calcutta. She recalls the thick albums of sketches that the director had created for every single film, each shot already visualised and sketched out before the film was made. This scrupulous methodology and attention to detail defined his work, and is something that everyone who worked with him noted and learnt from. The whole world loved him; and yet he remained simple and unaffected by his own international fame and influence.

The choice of Amjad Khan for Wajid Ali Shah is emblematic of Ray’s keen eye for actors and characterisation, observes Saswati-di. All the other cast members in the film – Sanjeev Kumar, Saeed Jaffrey, Shabana Azmi, Leela Mishra – were selected with the same meticulous and uncompromising care. And this detailed methodology was to be found in every aspect of his work.

Saswati Sen sums it up thus:

“A gem of a person! You don’t see people like this. We work in film, we still do. But there are very few people as great as Dada and yet so simple, so unassuming.”

She recalls an incident on set that exemplifies this. A curtain needed to be put up in the set on a high doorway – it was a darbar set, after all. A rather short workman was standing on a mora and trying valiantly to reach the required height. Ray noticed this, went up to him and said:

“Ei Chotu! Hat ja. Yeh mera kaam hai, tera kaam thori hai! Bhagwan mujhe itna lamba banaya hai isi kaam ko karne ke liye. Tu kyu karega? Yeh mera kaam hai. [Hey shorty! Move over. This is my job, not yours! God has made me so tall to do jobs like this. Why should you do it? This is my job).”

And he took the hammer and nail, and hammered the curtain into place.

Visibly emotional, Saswati-di remembers the last time she met him as he lay ill in the ICU at Belle View:

“I think it was immediately after the Oscar Award that he was given, and the Bharat Ratna was also given to him when he was totally indisposed in the hospital. So I went to the ICU, and there was a small hole in the tinted glass of the door. I peeped through, and his face was turned towards the door – every patient actually always looks towards the door to see family and friends coming. So I quickly retreated. He called his nurse and said – Bahar jo aayi hai unko andar laiye (Please bring in the person who is outside). And then the nurse came and told me, he is calling you. I said, no, no I don’t want to disturb him. I just came to see him because I felt like coming for two minutes. But she said, he has called. So I then cleaned my hands, took off my shoes and went in. He held my hand and said – Ki holo? Ashchili na? (What happened? Why weren’t you coming in?) I said – Na Dada, ami apnake disturb korte chai na, apnar kkhoti korte chai na. (No Dada, I don’t want to disturb you, I don’t want to harm you in any way). He said – Na! Tui ashle amar bhalo laage. Tui toh amar meyer moto. Tui ele kokhono ami disturb hobo na. (Not at all. I feel good when you come to see me. You are like my daughter. I will never feel disturbed by you). I feel happy seeing you.”

More than four decades later, Saswati Sen is still enjoying laurels from the film that changed her life, often introduced to those outside the classical music and dance world as ‘the dancer from Shatranj’.

“He had told my parents – we won’t ask your daughter to do anything compromising. She will be dancing exactly as her guru has taught her. And he had guaranteed, the day the film is released your daughter will be a household name in Bengal at least, and further all over the world.

And it was so!”