Navratri Highway Stars

On the first day of Navratri this year, I travelled a little over three hundred kilometres by road from New Delhi to Uttarakhand. All along the way, I saw idols of the great Goddess Durga being transported to the various locations where She would be installed for Navratri prayers and celebrations. Those with resources that did not allow for pomp and splendour carried the idols of the Goddess on little carts or rehdis used by small vendors in all parts of India, cheerfully walking alongside in small clusters. Others transported the idols on open body trucks with larger crowds of devotees, usually male, perched wherever they could on the truck.

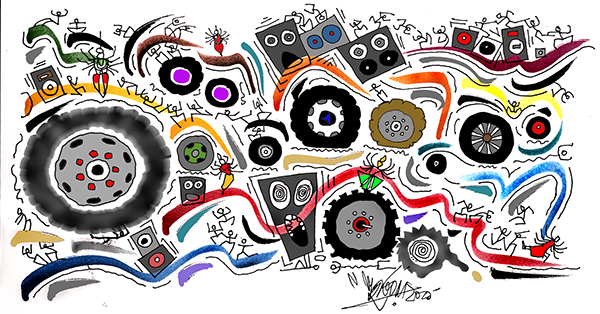

This is probably a familiar sight for anyone who has lived in India, but I write about it only because of the aural experience that accompanied the familiar sight of these processions, big or small. Almost each of the processions had music systems and speakers piled high on their carriers, blaring music at dangerously high decibel levels. Even before the processions were visible on the highway, they were audible. And what one heard invariably was the vehicle shaking, body racking thump of electronic drums and rhythm machines with some singing and music that was not always clearly audible. Even the more humble processions on carts had their music systems in place; albeit smaller ones. But the trucks had stacks upon stacks of speakers piled sky-high, tied together by nylon ropes to prevent them from dropping off, and many had male devotees in high spirits with red chunnis tied around their foreheads perched fearlessly atop the highest speaker.

Union Minister for Transport, Nitin Gadkari was recently reported as having announced that he would soon bring a law that permitted only pleasant sounding Indian instruments such as “Flute, tabla, violin, mouth organ, harmonium,” to be used as horns for vehicles. It would appear that the Minister has his work cut out with this project if the sounds of the Navratri processions are anything to go by. While he wishes to replace the usual sounds of vehicle horns with Indian instruments, our devotees on the highway seem hell bent on discarding traditional instruments like dhak, dhol etcetera in favour of non-Indian drums and electronic instruments amplified at ear-splitting levels. Will the Minister also decree that celebratory processions will not be permitted to play music at such high decibels? The processions of course, were moving through the highway and roads manned by both police and traffic police, but if attempts were made by either of them to ensure the safety of the public at large, I was not able to witness them as I drove past the din. However, what seemed apparent was that no one seemed perturbed about the possibility of the serious injuries that precariously perched devotees could cause to themselves if they dropped off, or the huge pileups that could be caused on the highway by a similar accident. Everyone rode by in merry disregard of the dangers that were evident. Sadly, this is the case with processions at other festivals too, across religions and communities.

It would appear that the Minister has his work cut out with this project if the sounds of the Navratri processions are anything to go by. While he wishes to replace the usual sounds of vehicle horns with Indian instruments, our devotees on the highway seem hell bent on discarding traditional instruments like dhak, dhol etcetera in favour of non-Indian drums and electronic instruments amplified at ear-splitting levels. Will the Minister also decree that celebratory processions will not be permitted to play music at such high decibels?

Navratri is typically an occasion when a lot of music was recorded and launched with much fanfare in India. Ranging from the very popular Pujo releases in Bengal, to Dandiya and Garba launches in Gujarat, Navratri was also a time for prestigious classical music festivals to be held in different parts of the country. In the past, one heard many an anecdote about the Durga Puja classical music festivals held in Patna and other cities in Bihar. This association of the festival and season with music has not yet become extinct, but like so much else, the nature of the music made and launched for Navratri has also changed rapidly. Traditional repertoire is fast being nudged out or neglected, while the big thump and grind routines are trending, and being promoted on social media platforms to achieve viral victory. The token appearance of dhakis, and dancers draped in laal paar sarees with dhunuchis does not usually succeed in conveying the magnificence and strength of the Divine Feminine force being worshipped.

This is by no means a lament against change, but a mere statement of fact not only in the context of music, but also in the context of the general slogans that are currently in vogue. Whatever happened to the Make in India slogan in the context of music? Some could argue that the music of the Pujo launches is being made in India, and indeed, these are Indian artistes who have a huge international appeal which perhaps traditional exponents do not enjoy. Conceding to that would not be a problem, but then why harp on the be Indian, make Indian anthems in all other spheres? If Yoga and Ayush can get new ministries, why not traditional arts? Where has all that pride in the ancient past gone in the context of music?

Traditional repertoire is fast being nudged out or neglected, while the big thump and grind routines are trending, and being promoted on social media platforms to achieve viral victory. The token appearance of dhakis, and dancers draped in laal paar sarees with dhunuchis does not usually succeed in conveying the magnificence and strength of the Divine Feminine force being worshipped.

Even as we welcome change and new music, we do need to think of our heritage of songs, ritual chants, music, drumming traditions and much more that we are fast losing as repertoires shrink, season and festival specific music fades into oblivion, and we come closer to turning into a mono music culture of demonic decibels. More importantly, it is not a hyper-nationalistic fervour that should drive or motivate us, but an understanding of the importance of bridging with respect the past, present and future.

Illustration by Suvamoy Mitra