Aranyer Din Ratri released in 1969. At that time I was extremely busy working in Hindi films. One day during the lunch break, an assistant came running to me and said, “Satyajit Ray wants to speak to you.” This was at Filmistan studio and I had to walk quite a distance to the office where the phone was. This was decades before cell phones made an appearance. Manik Da was waiting patiently at the other end of the phone. What he said made my heart sing with joy. He had a part for me in his new film. Would I be interested? Only thing was the dates were predetermined as it was an ensemble cast. Also we had a month’s shooting to complete before the rains arrived. The entire film was going to be shot on location in a forest in Chhipadohar, miles away from Ranchi.

When my heart had calmed down a bit it suddenly came to me that I had committed the exact same dates to Shakti Samantha for a song sequence for Aradhna in Darjeeling. He had Rajesh Khanna’s dates and changing that would be a nightmare. And even he had to finish the shoot before the rains. I realised I had a problem but I was also determined to solve it.

I don’t remember the sequence of events but it was definitely a testimony of my diplomacy and charm that I managed to get my way. Shaktiji agreed to do my close-ups later in the studio and allowed me to go for my outdoor shooting for Aranyer Din Ratri. I think it was very generous of him. He realised that how much working with Ray meant to me and he sportingly granted my request. As it happened Aradhna broke all records at the box-office, so even if Shaktiji was a little peeved at that time, all was forgotten.

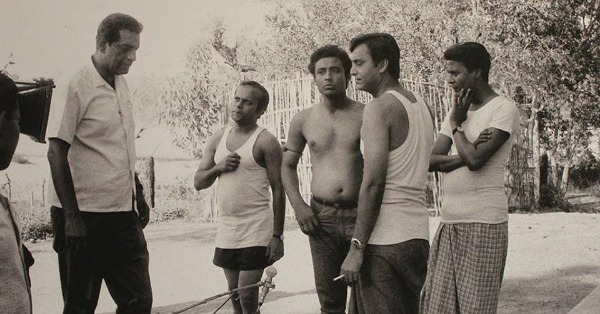

I had never enjoyed a film shoot as much as those days and nights in the forest. The location was absolutely stunning. The forest of Palamau, in the simmering heat of April, with its skeletal trees, scorched leaves piling up under a limpid sky, was simply magical. My co-stars Soumitra and Robi Da — my dearest friends — Subhendu, Samit, both wonderful actors and I stayed together in a make-shift accommodation. Kaberi Di and Simi stayed further away in a dak bungalow. Kaberi Di was working in a film after a long gap.

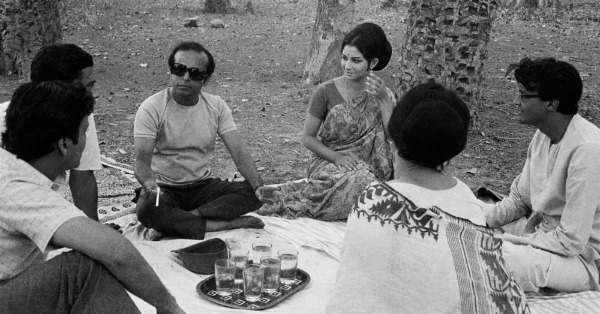

The outdoor shooting of Days and Nights in the Forest remains so vivid in my memory. We spent a month in middle of a forest. The month was April, the temperature spiked to almost 48 degrees Celsius during the day. We worked for about three hours early in the morning and then three again in the early evening. The rest of the time it was just “adda”. Sometimes Manik Da would drop in to join us, until he realised that everyone was hiding their cigarettes and becoming overly respectful. Robi Da had added an epithet to everyone’s name. Robi Pora (burnt), Samit Bhapa (steamed), Subhendu Bhaja (fried) etc. I was the only one who had a room with a cooler — the prerogative of being a woman — and I never heard the end of it.

Nearer the full moon nights, the forest became magical. We could hear the trumpeting of the faraway elephants and the intoxicating rhythms of the Santhal drums. I remember once, all of us, on a whim, went to meet the Santhals and danced with them till late into the night. Manik Da never got to know. One evening, some rough characters came to where I was staying and created quite a nuisance. We were far away from the police posts and in those days, no one had bodyguards. But Soumitra and the other boys managed to chase them away — by no means an ordinary feat. I knew then that I was amongst people who cared for me deeply.

Aranyer Din Ratri, based on a novel by the acclaimed author and poet Sunil Ganguly, was the beginning of Ray’s effort to understand the youth of the time. Ray’s script made a few departures from the novel, which met with disapproval from the author. For instance, he changed the class character of the protagonists. The unemployed youth who travelled ticketless in trains in Ganguly’s novel were, in the film, changed into four well-heeled middle-class men, three of whom held jobs, while one even had a car. Perhaps it was the educated middle-class (to which he belonged and understood well) that Ray held guilty of becoming ‘nowhere people’; of being divorced from their environment and of being oblivious to the impact of their actions on those who they considered their intellectual and cultural inferior — in this case, the tribals of the region and the chowkidar and his family.

In this film, Ray attempts to understand the new generation who seem to live in a vacuum, who can waste endless film time asking whether to shave or not. They keep striving but the goal remains tantalizingly on the horizon, leaving them frustrated. They have no idea what they’re looking for, leave alone how to get it.

At one level, the film could be seen as a romantic comedy about four educated young men escaping into a forest resort for a reprieve from the cacophony of the city life. How their ‘days and nights’ in the forest transform the young men is the central theme of the film.

What starts out as a spree ends up changing the lives of three out of four. The agents of this change are two women who also have come for a vacation in the forest. Of the four, Ashim is easily the worst. He is superior, disdainful to subordinates, most intelligent and very frustrated with his life. He feels he has somehow missed the bus. Sanjoy is timid, therefore prone to compromise. He is very shy with girls. Hari is a sportsman unlike the other two, he has no pretence to intellect. He has a boyish charm and he uses them on girls. He has an inferiority complex which he tries to shrug off. Shekar, on the other hand, is happy-go-lucky, a hopeless gambler, a Jack-of-all-trades, gives the impression of being with it but really is a prude. He is played superbly by my friend Robi Ghosh. His and Kaberi Di’s performances are probably the best in the film.

What attracts the young men to the forest is what they have read in a book about its untamed wildness. The idea of the male and female tribals drinking together, their scanty clothing, kind of excites them. Ray’s women in this film are creatures of superior moral sensibility and his men are all helpless children, as one critic bemoans. Again, as in Nayak, I play the conscience in this film. Ashim is confidently condescending to women, but Aparna, a city girl, and my character, is not impressed. Her non-judgmental attitude, common sense and her ability to appeal to his better self makes him feel somewhat foolish. Through her he rediscovers his humanity.

At another level, the film underlines the melancholy and corruption of the city’s class and creed, the cultural tragedy of imperialism that they all suffer from. It points out how urban living isolates us from a natural environment and blunts our moral values. There is a delightful irony — Ray seems to say in the film — that those who cannot appreciate a forest or a sunset without the crutch of western literary tropes should somehow consider themselves culturally superior! Alongside one sees the unaffected grace of the local tribesmen and one realizes how contrived the civilized city people really are. This alienation was understood better by the western audience than the audience at home. The film was very popular and ran to packed audiences in Paris and New York. They loved Robi Da. Every time he arrived on the scene the audience burst into a spontaneous applause.

The end is perfect, the four go back but now they are different, more human — all except Shekhar, who remains the same.

There is a subtle but ominous hint that even the forest may not remain the same much longer. Today a large tract of these tribal lands is a seething cauldron of unrest. The avarice of city people surely has had a role in it. After bribing the chowkidar, Ashim casually boasts, “Thank God for corruption”. Those words continue to haunt. Several years later, I’m afraid that is exactly what has happened. Our forests are no longer the safe haven of peace that they were then. Gautam Ghose’s sequel Abar Aranye, which has the same characters returning to the forest thirty-odd years on, explores how a whole way of life has vanished, with violence palpable under the façade.

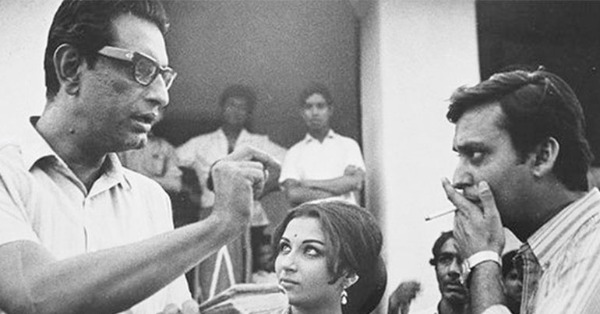

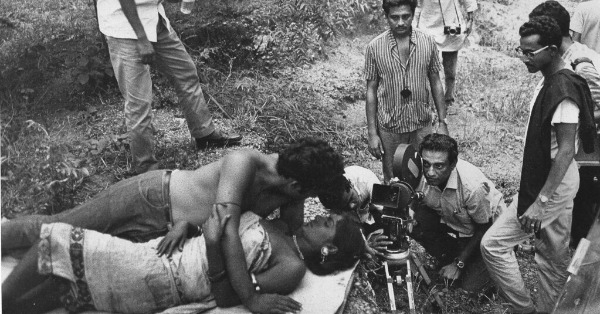

Here I just have to mention the scene of Jaya’s overtures towards Sanjay. Although there had been subtle hints of her loneliness, Jaya has been mostly relaxed, hospitable and cheerful. So her sudden burst of passion comes as somewhat of a surprise. It brings to the fore her longing and desperation. But Sanjay is too timid to offer her any comfort. The moment passes — a dejected Jaya withdraws in a flood of tears. It is the most poignant scene of the film and Kaberi Di is brilliant. The other highlight is Manik Da’s camera operation, which he did for the very first time in this film. Subrato Mitra was no longer part of the unit. The way Manik Da filmed the memory game is nothing short of genius. To pan from one face to another in a big close up and back, while the camera is moving forward on a trolley, is challenging, even for the most experienced. Particularly when the camera is an Arriflex — the viewfinder with its moving shutters obstructs rather than offer a clear vision and yet Manik Da’s hands remained steady — his timing perfect. There were no retakes. We had a couple of hours to shoot the scene before we lost the light, but Manik Da and us, the actors were prepared and we wrapped up on time. And what an iconic scene it is.

Sadly, so many of the cast and crew have passed on. Kaberi di, Robi Da, Subhendu, Samit, Bansi Da, Manik Da and now Soumitra. No one is left to recollect and share the joy and exhilaration of those days and nights we spent together in that age-old forest under the all-encompassing sky of Chhipadohar. I brought back a bottle of mahua as a keepsake but the odour was all too much for the other occupants of the house and ultimately I had to get rid of it.