Helpless, hyper-masculine Hindu gods

দেবদত্ত পট্টনায়েক (Devdutt Pattanaik) (July 9, 2021)

দেবদত্ত পট্টনায়েক (Devdutt Pattanaik) (July 9, 2021)To anyone who appreciates art, it is clear that the image of ‘Rudra Hanuman’, now popular as car stickers in Bengaluru and other cities of India, was strongly influenced by the poster of the Hollywood film, Rise of the Planet of the Apes. Such reinterpretations have been rather common in the past few decades – Rama now needs to have a six pack, so does Shiva, even Durga, and brooding expressions, as they prepare to kill the bad guys, like a DC comic book hero such as Batman, or even the new Superman. Even Amar Chitra Katha’s new comics have abandoned the gentle sensuality of Raja Ravi Varma and embraced the hyper-masculine, angry, violent American superhero style to portray Hindu gods and goddesses.

This trend has been appropriated and legitimised by Right-wing politicians, those who follow a unique brand of Hinduism that they call Hindutva based on hating Muslims, and on venerating the cult of toxic masculinity. As a result, many intellectuals have got their knickers in a twist. How dare they? This is not our Hanuman, say writers who otherwise would insist they are not religious, but spiritual or agnostic, and who probably frown upon the irrational practice of visiting Hanuman temples on Tuesdays (in Delhi) and Saturday (in Mumbai) to pour oil on the deity so that he removes all malevolent astrological influences from their lives.

The image has captured the imagination of the public as indicated by its popularity. Is the art and its popularity an expression of widespread Hindu anger at being taken for granted and constantly in need of ‘reform’? Is the rise of the Right-wing government the cause or the consequence of this anger? Or is it just popular kitsch? Maybe it is political propaganda? Or is being made into a political tool by serial opportunists?

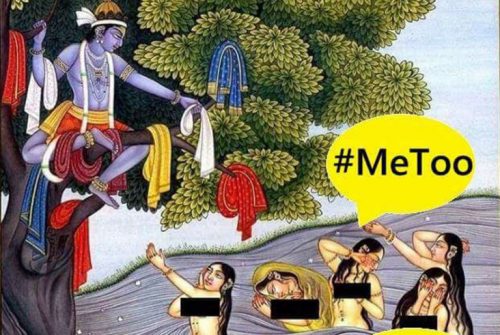

Hindu gods and goddesses have been used cynically by the Left and the Right, and artists to convey political messages. In WhatsApp forwards, one gets images that reframe Krishna stealing women’s clothes while they are bathing in the Yamuna as a case of cultural sanction of rape. This is not differentiated from Kauravas disrobing Draupadi. For the artist, and those who forward it, Krishna’s childhood prank is no different from the Kaurava malice. Is this a postmodernist distortion of a traditional Hindu tale or authentic understanding of Hindu lore? As in the case of Angry Hanuman, who decides what is the correct reading of Hanuman, or Krishna, or Rama, or Shiva, or Durga, or Kali? How must they be reframed in the 21st century?

In WhatsApp forwards, one gets images that reframe Krishna stealing women’s clothes while they are bathing in the Yamuna as a case of cultural sanction of rape Under British colonial influence, Raja Ravi Verma ensured all Hindu gods and goddesses looked like fair-complexioned Brahmin men and women. Dark gods became blue gods. The Indian goose (hamsa) found in traditional Indian art, was replaced by the long-necked and supposedly more elegant European swan (raj-hamsa). Many artists used European Renaissance paintings as their template which is why many a time Krishna and Radha look more European than Indian.

Now, in the era of American DC and Marvel comics, Hindu gods are becoming superheroes, angry with the mess that the world is in, determined to solve the problem and fix things, like a biblical prophet or an archangel.

Determined to see Indian gods in European and American terms, in form and content, we are losing sight of Hindu ideas and Hindu art. Unlike Greek and Roman gods who sport musculature and tend to be portrayed realistically and ideally, Hindu gods on Hindu temple walls are softer and rounder, and portrayed stylistically with a dancer’s grace, almost always stuck in a well-calculated geometric frame. This style was formalised and became popular from the 5th to 15th century.

Determined to see Indian gods in European and American terms, in form and content, we are losing sight of Hindu ideas and Hindu art. Unlike Greek and Roman gods who sport musculature and tend to be portrayed realistically and ideally, Hindu gods on Hindu temple walls are softer and rounder, and portrayed stylistically with a dancer’s grace, almost always stuck in a well-calculated geometric frame. This style was formalised and became popular from the 5th to 15th century.

Even angry forms of Shiva and Shakti were shown so gracefully that one overlooks its grotesque nature, the decapitated heads, the pile of corpses, and the cups full of blood. This is not expressionist or impressionist or idealistic art; this is representational art, designed to do the same thing that a Vedic yagna or a Puranic tale is designed to do – communicate ideas to the common man. Some needed ritual, some needed narratives, and some needed art, to appreciate the wisdom.

Anger is an indicator of helplessness. Hindu gods are never helpless as they possess infinite wisdom. That is why they don’t look distraught or angry in battlefields, or in exile. They look calm and composed because they know the full picture, the past and the present, the here and the beyond. Like a parent helping a child to learn how to walk, they are engaging with humans at a human level. While superheroes are ordinary beings who become extraordinary, Hindu gods in all their manifestations are infinite beings who choose to become limited, as kings and monkeys, to help humans discover their divine potential, to think beyond themselves and embrace the other.

While American superheroes are busy saving the planet from super villains who seek world domination, Hindu gods – including Hanuman– are teachers, who uplift (uddhar) us not from problems but from our limited understanding that makes everything around us a problem. In wisdom, we see how the world functions, and we realise what is a problem for some is a solution for others. Rama fights Ravana not because Ravana is evil (a Judeo-Christian word), but because Ravana has been enchanted by his own power and knowledge and is unable to rise up to his human potential. Ravana clings to power like a dog clings to his bone, and so is unable to break free and fly like Hanuman.

In Indian wisdom, Hanuman is not a problem-solver, though he is called sankat-mochan in the Hindi belt. For when gods solve our problems, they do not contribute to our intellectual and emotional growth. And if we do not grow intellectually and emotionally, we waste our lives as human beings, and remain self-indulgent pleasure-seeking animals. Of all the monkeys who encounter Rama in the forest, only Hanuman transforms from Rama-das (servant of Rama) to Mahabali (the multi-faced multi-armed deity who stands autonomously). This transformation from animal to divine happens as he moves from being dependent like Brahma to independent like Shiva to dependable like Vishnu.

পূর্ববর্তী লেখা পরবর্তী লেখা

Rate us on Google Rate us on FaceBook