The Shadow on the Wall

রাস্কিন বন্ড (Ruskin Bond) (May 22, 2021)

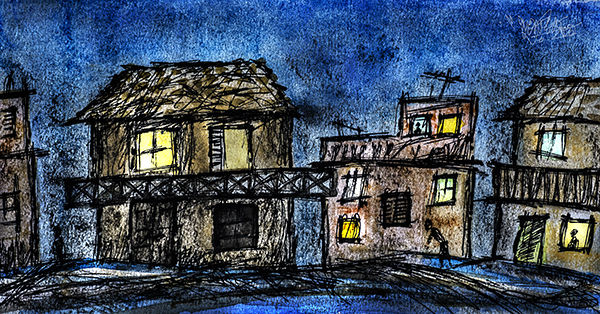

রাস্কিন বন্ড (Ruskin Bond) (May 22, 2021)When I was in my early twenties, a struggling freelance writer, I rented two small rooms above a shop in Dehradun, and settled down to make my fortune as an author. Or so I hoped.

The rooms were without electricity, the landlord (the shop-owner) having failed to pay the electricity bill for several years but this did not bother me. Dehra wasn’t too hot in those days, and I had no need of a ceiling fan. And I thought an oil-lamp would be sufficient and even quite romantic. Hadn’t the great authors of the past penned their masterpieces by the light of a solitary lamp? I could picture Goethe labouring over his Faust, Shakespeare over his Sonnets, Dostoyevsky over his Crime and Punishment (probably in a prison cell), and Emily Bronte composing Wuthering Heights by the light of a flickering lamp while a snowstorm raged across the moors that surrounded her father’s lovely parsonage.

So many geniuses would have written by lamplight – Prem Chand in his village, Keats in his attic, poor John Clare in a madhouse… Well I was no genius and I had no wish to enter a madhouse, but I liked the idea of writing by lamplight, so I invested in a lamp and a bottle of kerosene, set up the lamp on an old dingy table (I took my meals at a dhaba down the road), brought it to a fine glow, and wrote my first story under its benediction.

I don’t remember what the story was about, but it wasn’t a bad effort, and I sold it to a Sunday magazine.

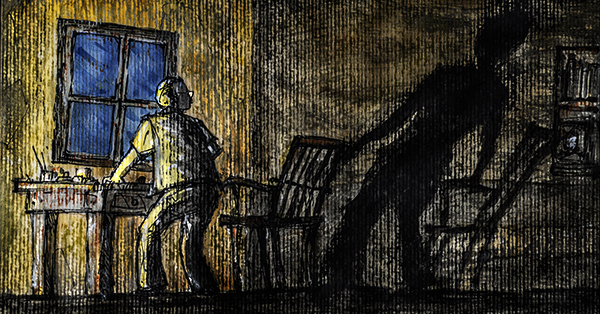

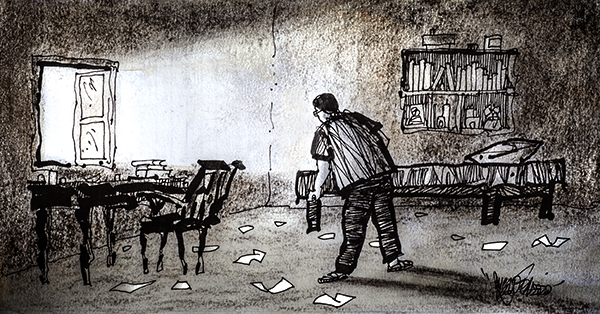

Every evening after taking my meal in the dhaba, I would light the lamp, settle down at the table and toss off a story or an article. I enjoyed the lamplight, even when I wasn’t writing. There was something soothing abut its soft glow. It threw my shadow on the wall on the other side of the desk; and whenever I got up and paced about the room (as I often do when writing) my shadow would follow, prowling about on the walls of the room, almost as though it were taking on a life of its own.

The two-roomed flat in Dehradun The shadow was always a little larger than life. The lamp seemed to magnify my image. Probably this had something to do with the glass or the position of the lamp.

And late one evening, while I was in the middle of a story, I chanced to look up – and there, beside my shadow on the wall, was another shadow.

It was the shadow of someone who was standing just behind me.

Someone was in the room, looking over my shoulder, reading what I was writing.

It is always irritating to have someone watching you while you work. Even in an exam hall, I could never proceed with my essay or answers if the supervisor was standing over me; I would wait for him to move on, so that I could concentrate properly.

So now, disturbed, I turned around to see who was looking over my shoulder.

There was no one behind me, no one in the room.

I can’t say I was frightened. But I felt extremely uneasy. Had I imagined the shadow on the wall – the shadow of the watcher? I looked again. It was no longer there.

I returned to my writing. But I was uneasy. I couldn’t help feeling that I was not alone, that someone was reading my manuscript as it was being written.

Well, doesn’t every writer cherish a reader? Why complain? If there can be ghost writers, there can be ghost readers.

And when I looked up again the shadow was there, standing beside my own seated shadow, very still, studying the page, my words, my stream of consciousness.

It was the shadow of a woman, of that I was certain. Her hair fell to her shoulders, the outline of her figure was feminine, and she was wearing a gown that trailed behind her. All this the shadow told me; but no more.

I put down my pen, covered my manuscript with a paperweight, put out the lamp, and went to bed. In the dark there are no shadows.

The dark has never really bothered me. With my poor sight I am just at my home in the dark as I am in a well-lit room. That’s why I like the lamplight. It is not too harsh, too intrusive; and beyond its circle of light, there is darkness, the friendly dark that is home to little bats, timid mice, and shy humans.

But lamps throw shadows.

And when I sat down at my desk the following evening, I was expecting the shadow of my solitary reader.

I had written a page or two before I became aware of her presence. I know she was there without looking up to see if her shadow was on the wall. The room had become suffused with an unmistakeable fragrance – attar of roses! She was speaking to me through the perfume of her favourite flower.

But I was not to be seduced. I carried on with my story – Time Stops at Shamli – completed a few pages, covered them up, put out the lamp, and went to bed.

My visitor must have been annoyed, because the scent of roses vanished, to be replaced by the strong odour of crushed marigolds. I covered my head with a blanket and shut out all scents and shadows.

Next morning, I found the pages of my manuscript scattered about the floor of my room. Perhaps the dawn wind had disturbed them. The window was half-open. Could my visitor have disturbed them? She was doing her best to make herself felt.

‘The pages of my manuscript lay scattered about the floor of my room…’ I started working in the morning instead of at night. The lamp would be given a rest except when really needed. Let the shadows rest. Let the phantom lady rest….

She did not like being ignored.

Late one night – it must have been about two in the morning, the witches’ hour – I was awakened by the most terrible shrieks. The room vibrated with the sounds of a shrieking woman.

I leapt out of bed, scared out of my wits, and lit the lamp, which now stood on the dressing table. The shrieking stopped. And shadows scurried about on the walls.

This happened night after night, for almost a week. Shrieks would wake me in the middle of the night, and would stop only when the lamp was lit. No longer did fragrance fill the air; just the smell of oil and something burning.

I confided in Melaram, the owner of the dhaba where I took my meals. He twirled his luxurious moustache, nodded sagely, and said: “It seems your landlord kept something from you – the tragedy of the woman who perished in your flat some five or six years ago. They were a childless couple, she and her doctor husband. They quarrelled a lot. One day when she was in the kitchen preparing their dinner, the Petromax stove burst, burning oil fell on her clothes and soon she was covered in flames. She ran on to the balcony, screaming for help, but by the time we could get to her she was in a terrible state.”

“And where was her husband?”

“Out, visiting a patient. He followed us to the hospital, but by then she had gone. In fact, there wasn’t much left of her.”

“So it was an accident?”

“The police called it an accident. But there were rumours – there are always rumours in such cases, and when the doctor left town and set up his practice in Delhi, there were more rumours. And then of course he married again….”

“All speculation,” I said. “But I’ve had enough of the lady’s presence. Her shadow seems real enough – and now those shrieks! I’m moving into the station hotel, and then perhaps you can help me find another flat. “

But I could not move immediately. Two suitcases held all my clothes and personal effects, but I had accumulated a cupboard full of books, and these, along with my notebooks and manuscripts, had to be carefully packed. It meant another night in my haunted rooms.

I went to bed as late as possible. I went to bed in the dark. Well, it wasn’t too dark, because a full moon threw its beams across the balcony. But I did not light the lamp; I’d had enough of shadows.

I was slipping into a dream when I felt that soft hand on my shoulder. Then the other hand touched me. I shivered with fright and apprehension. The hands moved across my chest and arms, there was nothing disembodied about them. I lay perfectly still.

I had asked Melaram’s young assistant to bring me a glass of hot tea at daybreak. I slept soundly. There was no shrieking that night. But I was awakened by a push on my left shoulder. And I started up and called out “What’s up? Why so early?” thinking it was the boy with my tea. The moonlight had gone and it was dark everywhere.

I got no answer. Instead I received another push.

This annoyed me, and I said, “Why don’t you speak, boy? Is something wrong?”

Still no answer, and as I began to sit up I felt a human hand, warm, plump and soft, slip into mine.

Still thinking it was the boy, I caught him by the hand, and with my free hand I encountered a wrist and arm, a long sleeveless arm. I felt along the arm, but when I reached the elbow all trace of the arm ceased. I was left holding a disembodied arm!

You can imagine my fright. I dropped the arm, tumbled out of bed, and rushed to the balcony calling for help. Melaram was up by then, and he and his boy came rushing to my aid with torches and an old firearm. But there was no one in the room, no remnant of a burnt or dismembered body. And soon it was daylight.

***

After a few nights in the station hotel, I found a bright cheerful flat just behind the Odeon cinema. It had electricity too. Although we were subject to long power cuts (which continue till this day), I was no longer dependent on the oil lamp, which I still possessed – just in case I couldn’t pay the light bills!

But somehow I missed the gentle glow of my oil lamp. I had a feeling I wrote better by lamplight than by daylight or the harsh light of electricity. The lamp provided the right kind of atmosphere for my writing; it created the mood I wanted, a touch of magic, a touch of melancholy, of motion undefined….

And so one evening I lit the lamp, and sat back in an evening chair, and watched the shadows on the wall.

But there were no shadows apart from mine, no one looking over my shoulder. In the words of the old song, it was just “my echo, my shadow and me…” And we weren’t really company.

The lamp stood on the dressing-table. I had come home late, after visiting a friend at the other end of town. I was too tired to do any work, so I left the lamp burning and went to bed. Outside, on the street, a clock struck twelve.

I was slipping into a dream when I felt that soft hand on my shoulder. Then the other hand touched me. I shivered with fright and apprehension. The hands moved across my chest and arms, there was nothing disembodied about them. I lay perfectly still.

That soft, warm, plump hand brushed against my cheek. I put out my own hand to touch her face. But there was nothing to touch. She was headless!

As I tried to get up, her free arm stretched out, stretched right across the room, and switched off the lamp.

Illustration by Suvamoy Mitra

পূর্ববর্তী লেখা পরবর্তী লেখা

Rate us on Google Rate us on FaceBook