Nayak – The Hero was released in 1966. It was India’s official entry at the Berlin Film Festival. Manik Da had wanted me to go but I couldn’t since I was shooting for An Evening in Paris at that time. Two more dissimilar themes you cannot imagine. It would have been such a privilege and a great memory to have attended a film festival with Manik Da, but it was not to be.

Nayak was Manik Da’s second original script, the first was Kanchenjungha. When he offered me a part in Kanchenjungha, I had my senior Cambridge exams and had to decline. Naturally, I was pretty miserable about that. So I was really excited when Manik Da asked me to play the role of a journalist, Aditi, in Nayak. This time also, like Kanchenjungha, he had written the screenplay himself.

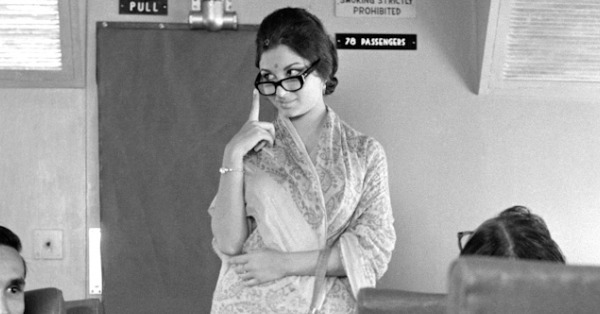

When we met, Manik Da said, “Rinku, you will have to wear glasses otherwise you will look too young opposite Uttam Kumar.” A veteran of two Ray classics already at that time, and with my baptism in Hindi cinema, I fancied myself a little more film-literate. So I asked him “Am I short-sighted or long-sighted?” He hadn’t thought of that and I could see he was quite taken aback before saying, “Well you can decide that”. Till that point, I had done whatever he had told me to without suggesting anything myself. He was quite amused and pleased that I was becoming more grown-up and professional in my interactions with him.

In all his films till that point, Manik Da had largely cast non-professionals. But, in Nayak he cast the matinee idol of Bengali cinema, Uttam Kumar, in the lead. A decision for which he got a lot of flak from critics including Mrinal Sen, another famous film director and his contemporary. They believed that he had sold out to commercial considerations. At that time, the common belief was that parallel cinema and mainstream popular cinema didn’t mix and shouldn’t mix. In a way, Ray broke that norm. This he did because he felt a star would be the most ideal choice to play such a character since the audience would identify with him instantly. Also, he believed in Uttam’s ability to deliver as an actor. Uttam, as I have said, was already a great success but after this film if I may say so, he became a much better actor. There is a scene in the movie towards the end where the hero is inebriated and he tells Aditi the reason his last film didn’t do well at the box office. He confesses that he had an affair with a married woman and therefore was distracted from his work. Uttam was splendid in that scene – I was merely a silent spectator.

Nayak is a collaborative product of three gigantic artists. Manik Da of course, Banshi Chandra Gupta (the art director) and Subrata Mitra (the Director of Photography). The interior of the star’s home with Philip’s electric shaver, British Airways toiletry bag, badminton racquets tell us that Arindam is well travelled and enjoys sports. His house with oversized framed images of himself proclaims his love of self. His shoes and fancy socks tell us that he’s a cut above the rest. Banshi Da’s eye for detail enhances Arindam’s stardom. Despite the budgetary constraints, Banshi Da replicated the interiors of the Rajdhani Express flawlessly.

In all his films till that point, Manik Da had largely cast non-professionals. But, in Nayak he cast the matinee idol of Bengali cinema, Uttam Kumar, in the lead. A decision for which he got a lot of flak from critics including Mrinal Sen, another famous film director and his contemporary. They believed that he had sold out to commercial considerations. At that time, the common belief was that parallel cinema and mainstream popular cinema didn’t mix and shouldn’t mix. In a way, Ray broke that norm.

The entire simulation of being in a moving train and stopping at stations, the perfection in lighting according to the time of the day was due entirely to the design and effort of Subrata Mitra. The trio’s contribution to cinema has been immense.

Filmmaking in Calcutta has always been a sort of technical battle, mainly as I said due to lack of funds. I am sure this added to the overall stress of filmmaking and I wouldn’t be surprised if this was the cause of Ray’s poor heart condition. I remember him sitting next to the camera during our lunch break, chewing on his handkerchief. He ruined one hankie daily much to Monku Di, his wife’s chagrin.

The story of Nayak is a study of the psyche of a ‘star’, his admirers, as well as his detractors. The hero decides to travel by train to Delhi ostensibly to collect an award but really to get away from it all. From a scandal involving a married woman and the disaster of his latest film at the box office. He feels defeated and needs to give himself time to clear his mind.

A young journalist who edits a women’s magazine, the character I play, is also travelling in the same train. She is egged on by her travelling companions to ask him for an exclusive interview. After the initial hiccups, the ‘star’ realises he doesn’t have to play a ‘star’ with her, which is hugely liberating for him. Aditi’s initial contempt turns into empathy when she realises he is human after all. She ends up becoming his conscience keeper. At one point she asks him, “Don’t you feel despite having everything there is a lack somewhere?” And at another point when he says “conscience is a terrible nuisance, I wish I could erase it completely”, she gently points out “but isn’t that what makes us human? Without a conscience what would become of us?”

David McCutchion says, “The delight of the film is its structure – the way the themes are patterned and the pleasure of recognizing the familiar, pin-pointed by art.” It dramatises the ordinary lives of a few people brought together in a carefully crafted manner. Manik Da sets up a perfect situation for romance and then stalls it. All the other passengers in the train are star-struck, unable to be normal in the presence of the star. All except a little non-Bengali girl and of course, Aditi.

The film has strong moral depth. It inspects the central moral issue from different angles – professional etiquette, friendship, compromise with one’s ideals for the sake of money, extra-marital relationships etc. The emotional tone of the film is extremely restrained.

In the confined and controlled space of the train, the hero tries to confront his inner demons. Some hero-worship him and some who have read the gossip columns despise him. He alternates between being a matinee idol and his real self. He knows as a star what is expected of him and he doesn’t disappoint. Almost everyone in the train is playing at something and is more than ready to pretend to be something they are not. In that sense, they are all acting.

Ray challenges our preconceived notions of a ‘star’. In Nayak, he poses many questions and offers no answers. He takes us out of our comforting assumptions and unsettles us.

“Is being successful in one’s craft, is failing at a deeper level?

Is art house cinema more ready to risk failure than the commercial blockbuster?

Are we constantly wondering how much to call on our own tradition and how much to be part of the global order?

Should we distract our audiences away from their travails and entertain our viewers rather than exploring their predicament?

Does anyone care about quality work?”

The film ends on an ambiguous note. The ‘star’ on arrival at the Delhi station is hemmed in by his admirers and Aditi walks away with the family member who has come to collect her without a backward glance.

Maybe this was the time for Ray to introspect. His dedication to his work was without parallel. There is a timeless quality about his films. There hasn’t been another Ray in Bengali cinema and we miss him enormously.