Chilla: Part 2

Nirmala was a fair, pretty woman with a lovely, smiling charm about her. Married, like so many other Indian women, when she was only sixteen, she had delivered her first child, a son, within a year of her being wedded to Nand Kishor Malviya from a prominent family in Varanasi. The couple had their second child, another son, a few years later, and were thus, parents of grown-up young men. N.K. Malviya, who started his career as an officer in the revenue services, now held a position of great seniority in the Ministry of Finance. At the time of their betrothal, Nirmala and N.K were complete strangers to each other, but over the years they were able to forge a relationship that was the cause of great envy for many. Nirmala was devoted to N.K and had dedicated herself unsparingly to looking after her home and family. In return, N.K. adored her and saw to it that all her wishes were fulfilled. As their sons grew up and his own professional life increasingly took up more of his time, N.K. encouraged Nirmala to find a hobby that would keep her occupied gainfully. Ever dutiful and obedient, Nirmala surprised N.K by asking if she could resume Kathak lessons, which she had willingly abandoned when she got married. Dance? At this age, when you are the mother of two boys? He had asked with a slight frown which she noticed immediately. Not if you don’t approve, she had said hastily but with a tinge of disappointment in her voice. No no, go ahead, he relented, probably because he was so certain that she would soon lose interest or abandon the exercise because of her many housewifely duties. He couldn’t have been more inaccurate.

He soon found himself accompanying Nirmala on a Saturday evening to meet Revati Guha, formerly a prominent Kathak dancer who now devoted most of her time to teaching a host of loving disciples. The purpose of the visit was to formally request guru Revati to accept Nirmala as her disciple. N.K was already waiting in the car when he saw Nirmala emerge from the sarkari bungalow allotted to them at Kaka Nagar, cheeks flushed with excitement, eyes aglow, followed by two of the kitchen staff, one carrying two big boxes of home made sweets, and the other a basket full of assorted fruits. A bouquet of gigantic pink and white lilies was balanced on top of the fruit basket. His eyes softened with affection for her as she settled herself into the car, shooting a volley of last-minute instructions at the kitchen staff. The driver had, in the meantime, arranged the sweets, fruits and flowers in the boot carefully, and soon, they were on their way to Revati’s apartment in the Asian Games Village where many artistes had been provided temporary accommodation once the Games were over in 1982. At their destination, they were welcomed and ushered in by two of Revati’s disciples. One announced that she would call “Didi” in a minute, and the other courteously asked what they would like to have – chai (tea)? thanda (cold drink)?

Before they could respond, Revati walked into the room, hands folded in greeting. With a gasp of excitement, Nirmala rushed towards her and touched her feet while N.K waited for his turn. Urging Nirmala to straighten up with a soft “Aray bas, bas” Revati turned to greet N.K. who also bent waist forward to greet her but was stopped mid-bend when Revati protested saying “Aray bhaisahab, what are you doing? Please take a seat. Nirmala now reached for the sweets, fruits and flowers, handing them over one by one to Revati who passed them on to her waiting disciples who in turn, carried them into the house. Nirmala sat back again and looked adoringly at Revati as she announced breathlessly that she couldn’t find words to describe the joy she felt at being in her presence. Finally she blurted out that it was her life’s ambition to resume Kathak lessons and become Revati’s disciple if only she would accept her. N. K. seconded Nirmala’s plea, urging Didi to accept Nirmala as her disciple. Poor Didi had no option but to concede in the face of such enthusiasm. Her newly accepted disciple now put forth the delicate question of dakshina or tuition fee, but Didi brushed aside the question saying instead that Nirmala should first start learning and this matter could be discussed at a later date. Despite repeated entreaties, Didi would have it no other way. Moved to tears and euphoric, Nirmala thanked her guru, and returned home dreaming of a new phase of her life, one where she would be in the service of Kathak.

For the next two years, Nirmala went to Didi’s home thrice a week for lessons. Not one to be daunted by slow learners, Revati did her best to teach her new student with her characteristic dedication, but with each passing lesson it became amply clear that Nirmala was one of those rare beings who could throw any teacher anywhere in the word a Teach-me-if-you-can challenge. All she managed to teach her was the correct method of tying ghungroos. Soon anyone watching Nirmala hitch one end of the stringed ghungroos round her big toe as she wound the rest of the string round her ankles skillfully would have imagined that she would be an experienced and skilled dancer. But the moment Nirmala started dancing, it was non-stop rib-tickling, sidesplitting comedy all the way. There was something manic and wild about the way she stamped her feet madly, huffed, puffed and panted crazily from the exertion, and of course, her chakkars (pirouettes) were something else. Lurching drunkenly in untidy circles, eyes and mouth wide open as if in shock and horror as she spun around, poor Nirmala pirouetted like an unstoppable lunatic. Anyone who watched could well have collapsed from too much laughter, but Nirmala had no idea of the effect she could have. She believed she was a seriously good dancer, a diva in the making. Revati tried hard to make her study each stance, each pose, each movement in the full length mirrors in her dance studio, which enabled students to actually see where they needed correction. It helped but only marginally, because the instant Nirmala started moving, the madness took over once again. Finally, two years after she first started learning, Revati announced to Nirmala that she could do no more for her. A kind-hearted woman, she could not bring herself to tell her Nirmala bluntly that she could not be taught, or that she was incapable of dancing. So she softened the blow by saying instead that that there was nothing more she could offer to her. Nirmala promptly decided that she had acquired from her guru a certificate of accomplishment. Expressing her gratitude, she assured Revati that she would continue to practice and would approach her for advice from time to time.

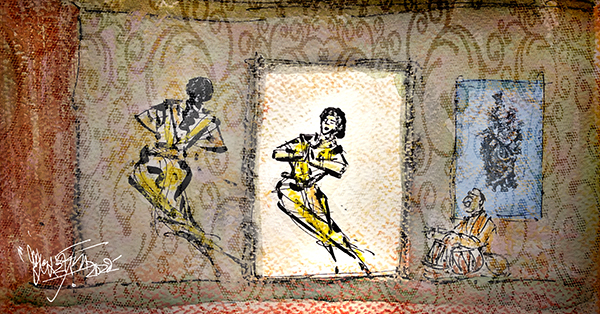

Nirmala believed she was now ready to share her art with the world. She first converted the courtyard at the back of the house into a dance studio, replete with full-length mirrors positioned on one side. Since she could not imagine doing anything without consulting N.K., the studio too had been sanctioned and approved of by the master of the house. The entrance had a small painting of Krishna as Natwar, the divine dancer, framed on it, and the words “gurave namah”or Salutations to the Guru hand painted underneath. Every morning Nirmala settled household chores and then religiously closeted herself in her studio. No phones, no disturbance, only riyaaz, which for Nirmala, meant two hours of stamping, heaving, stretching, pouting, trying absurd poses and movements in some sort of crazy self-regulated ritual. Sometimes she would also engage accompanying musicians for her riyaaz. It was in the studio that she imagined herself turning into a danseuse par excellence, an acclaimed artiste who had managed to serve her art even as she remained faithful to home, hearth and spouse. And it was in the studio that she came up with the idea of an annual performance, organised on a grand scale.

With her usual grit and determination, Nirmala set about the planning and execution of her grand performances and before long they became a laughing point for many, if not a talking point. Everyone laughed at her dancing, made fun of her unreal ambitions, and yet did not fail to show up at her annual events. Some came to please N.K. hoping to curry favour with him. Others came just for a laugh and to bitch about everyone including themselves. But a few women came because they saw in Nirmala a role model, someone who had escaped the humdrum existence of family life to pursue her interests without causing an upheaval. Still others came out of sheer affection for the Malviyas. But between the two of them, the Malviyas managed to collect people annually for a good laugh and some nasty gossiping and backbiting courtesy Nirmala’s dance. The only people who did not find her work laughable were the Malviya couple themselves – Nirmala, because she believed deep in her heart that she was a fabulous dancer, and N.K. who could not get himself to see anything funny about his beloved wife. Deeply embarrassed by their mother’s mad capers, the Malviya boys avoided being on attendance at their Amma’s performances by informing their shocked parents that they did not understand Kathak and traditional arts, and found the whole event funny. Funny? Questioned a bristling N.K. You find your Amma’s hard work funny? Suniye, let them be. Theek hai, beta. Its ok, you don’t have to come if you find it funny. Hurt but not beaten, she directed her attention to other pressing matters at hand.

Years after she started organising her annual performance Nirmala noticed that fewer people were attending her concerts in the last couple of years. Maybe she could try something different this year to grab everyone’s attention. A theme, perhaps? No? Maybe integrate a group of Langa Manganiyar musicians along with her ensemble ? Not a bad idea but it could run the danger of her being branded a folk dancer, and that she could not tolerate, no way. It was sometime during the churning of all these ideas that she hit upon the chilla brainwave. Initially the accompanying musicians thought of ignoring her suggestion, believing the idea would be nipped in the bud promptly if it received no attention from them. But when they realised that there was no getting away from it, the first one to try and dissuade Nirmala was Ganga bhaiyya. He declared- A chilla is to be observed in isolation, not in the presence of hundreds of people, samjheen aap Mydum? Underish-stood?

Understood, Ganga Bhaiyya – retorted Nirmala. But we need to share these traditions with people, and create awareness about them; otherwise there will come a time when people will need a dictionary to understand the term chilla. In my own family my sons have informed us that they do not understand Kathak and find traditional performing arts “funny”. So if we don’t start creating awareness, the day is not far when people will think a chilla is about chilling. Underish-stood, Bhaiyya ji?

Sensing imminent defeat in this direction, Ganga Prasad tried another tactic and cautiously asked Nirmala if she thought she would be able to dance for 24 hours non-stop. What do you think Bhaiyya, you have been a part of my team for so long? What does your gut instinct tell you? The counter questions were posed in a controlled but challenging tone, accompanied by an icy stare. A trifle subdued, Ganga bhaiyya answered thoughtfully – maybe you can do it, but at my age, errr, ummm, I’m not so sure how long I can play non-stop. Pat came the reply- Okay, in that case, we can have more than one accompanist. In fact, I will ask Bina to draw up a list and call to see who will be available. Twelve tabla players should be enough, shouldn’t they? Or is it too much to expect each one to play even for two hours each?

Inextricably linked with the chilla was Nirmala’s wish to set a Guinness world record for dancing. And so, preparations began on two battle fronts – the chilla front and the Guinness front. As soon as she got a moment with N.K., Nirmala asked if he could instruct someone to find out about the process for submitting an application for a Guinness World Record. Baffled by the request, he asked her for details and realised that it was his wife who wanted to check if she could establish a world record for the longest dance marathon. Perturbed by her new-found ambition, he worried for her health and well being, but played along for the moment for fear of disappointing her. Fortunately, a preliminary inquiry revealed that the world record currently had been established by an Indian Mohiniattam dancer who clocked a performance of approximately 123 hours. N.K. hoped that faced with the rather intimidating fact that she would have to dance non-stop for over five days to break the current record and establish a new one, she would change her mind. Not to be daunted, Nirmala paused for a few moments to digest the information before asking if she could apply for a world record specifically in Kathak dance. It was now N.K.’s turn to be irritated and he retorted with exasperation – I will have that checked but from the little I have understood of these records, you can’t be too region- or style-specific. It must have some universal acceptance. That settled it for Nirmala. If this was something that displeased N.K. she wasn’t going to have any of it.

She retracted in an instant saying – No, forget it. It isn’t worth it. There is no need to assess a dancer’s ability based on the number of days he or she can dance non-stop. Dance for an hour, but dance well. That’s my motto. I’m not interested in establishing any world record. N.K, felt an immeasurable sense of relief and quickly exclaimed- Yes Nimmo, (using her diminutive nickname affectionately) you don’t need any of these world records. Just enjoy yourself and let world records be. It was decided then that the world records would be ignored but the Malviyas would proceed with the chilla in public gaze for a non-stop 24 hours.