Sab Lal Ho Jayega’: Maharaja Ranjit Singh, predicting that India’s map will turn red, as the British take over India.

‘My little black prince.’ Dalip Singh, the last king of the Punjab, as described endearingly by Queen Victoria.

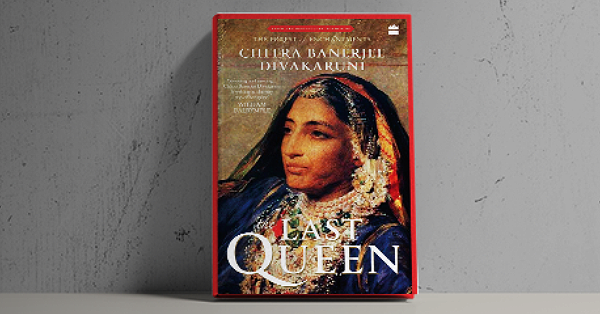

Between these two milestones in the history of the Punjab, Rani Jindan is often reduced to a coloured pebble along the way – interesting, pretty but not critical to the journey. Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni attempts to bridge this gap with her historical novel The Last Queen which speaks through the voice of Rani Jindan and gives us an imagined yet fact-based view of the queen as she travels from idyllic anonymity to zenana intrigue to durbar conspiracies.

Banerjee Divakaruni has always relished the challenge of getting into the hearts and minds of famed female protagonists. Whether it is the dilemmas of Draupadi or the anguish of Sita, the author has always brought life into her protagonist, making them speak a language that resonates with readers of our times. With Rani Jindan, the same skill holds her in good stead for the better part of the novel.

If anything, Rani Jindan comes into her own as she moves from ‘girl’ to ‘bride’ and then beyond to ‘queen’ and ‘rebel.’ These are the four sections of the book, which really hits its straps from late in the second section.

‘The first half of the story was difficult to research because there are very few sources of information,’ says Chitra about her research for the novel. What is known is that she was the kennel keeper’s daughter, that she was very close to her brother Jawahar (a relationship that causes her to make some fatal errors of judgement later) and that she was beautiful enough to make royal heads turn.

Banerjee Divakaruni manages the love story between Maharaja Ranjit Singh and young Jindan with the ease of someone who is on familiar territory. It’s however the chess-like encounters with the Maharaja’s other queens that make excellent reading. The hierarchy of queens, the plots and plans of the seniormost Mai Nakkain, and Jindan’s friendship with Rani Guddan, make it clear that Jindan is her own woman, not just a consort to her king.

The triumph of the author is that she has not shown Rani Jindan in pure white. She is always a woman with forbidden appetites and overweening ambition. Even at the depths of anguish, when the Maharaja dies, Banerjee Divakaruni gives voice to Jindan’s lust for life as a woman and not as a dutiful, widowed mother: ‘For my own sake, too, I want to live. I’ve barely touched the world. There’s so much out there to see and feel and taste. I’m greedy for it. I’ll take the bitter with the sweet. I’ll endure the pain.’

The triumph of the author is that she has not shown Rani Jindan in pure white. She is always a woman with forbidden appetites and overweening ambition.

Jindan proceeds to see an opportunity for her son and she grabs it, she feels and embraces the need for male companionship and she greedily tastes the elixir of power as she manipulates the court and, in time, the all-powerful Khalsa army. Punjab history remembers Jindan as Mother of the Khalsa – Mai Jindan, because of her short time as regent to a very young King Dalip.

The other area where the author scores is in showing how Rani Jindan cannily subverts the tools of patriarchy to win over the durbar. She unveils herself dramatically before the Khalsa army to show that she considers them her family. She also uses her husband’s name to gee up the army and her own image as a widowed helpless mother to a toddler king to keep her durbar under control. Each time she sees an opportunity to out-manouevre her opponents, she uses her beauty, her vulnerable status and indeed her unveiling to win support.

The final movement of the novel is ‘Rebel’ which deals with one of the saddest chapters of colonial history. A 10-year-old Dalip Singh is parted from his mother and systematically indoctrinated to look down on all things Indian. Worse, he is converted to Christianity and made to live off Queen Victoria’s court. By now, Banerjee Divakaruni has enough source material for the narrative to be more historically accurate. Rani Jindan, now partially blind, and far frailer and aged than her forty-odd years, meets her son and travels back to England. The mother in her trumps the patriot but more importantly, she wants to reclaim her son from the clutches of the imperial court and the other queen, Victoria. Even if it means she has to die away from her beloved Hindustan and indeed, Lahore.

As the novel closes, one misses an epilogue that could have chronicled Rani Jindan’s ‘Final Journey’ to Lahore. However, Banerjee Divakaruni does what every good historical novel should: she makes us want to know more about the protagonist, her times and the historical details and context of the setting.

Kolkata features at critical points in the novel, as the place where Rani Jindan meets her now grown-up son at the Spence’s Hotel (the hotel was located in Government Place East but does not exist anymore). And when Rani Jindan gazes at her beloved Hindustan, it’s the Kolkata riverfront she sees.

The detail of settings and the way Banerjee Divakaruni sets up her novel has always been visual and entirely cinema-worthy. Reports confirm that The Last Queen will move from page to screen shortly, with Endemol Shine having optioned the novel. One can hear Kangana Ranaut licking her lips on the sidelines. The accomplished actress would certainly relish the chance of playing this passionate, multi-faceted, beautiful queen. And we would hope it would keep her away from her Twitter handle, at least for a short while.