Satyajit Ray never became an ex-filmmaker. He remained immersed in his creative universe till the very end – even when his health was failing. What’s more, his films and his writings show a man who was a young soul – curious and completely engrossed by the places he visited and the experiences he gathered.

Being a filmmaker myself, I am overwhelmed by the rigour and commitment that Ray showed to his craft. I recently watched a BBC documentary which followed him as he prepped and later worked on the sets of a film. It was a rare, priceless insight into Ray’s process. With barely a decade’s experience, I can testify to the intense hard work and how it can be a soul-sucking process. One would also have to factor in how difficult it was for Ray to get resources for his films. For me, this rigour is as inspiring as the cinema that resulted from it.

I discovered Satyajit Ray rather late, and I discovered his writing before his films. Stories like Fritz were my first introduction to him and Fritz in particular really drew me in because it was such a wonderful piece of macabre. There are other stories, too, that make me wonder whether the man’s genius lay at least in equal measure in his writing as in his filmmaking.

As far as Ray’s films were concerned, finding good prints was a problem, as my student years coincided with the transition from DVDs to digitally restored prints. When I did get access to better prints, Ray has provided me with some amazing breakthrough moments over the years.

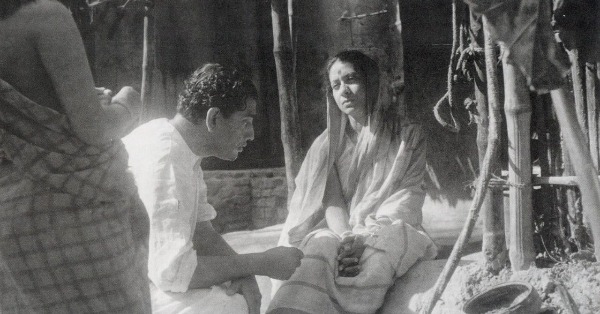

One such moment was when I saw Pather Panchali around five years ago at the MAMI Film Festival. It was a fantastic print from the Criterion collection, and that was a cinematic experience I was not prepared for. I would have to say that I do not think Ray has made a better film! The cinematic magic, the camerawork, the way the story washed over the viewer, makes me choose this film over the rest of the trilogy. Aparajito and Apur Sansar did have memorable moments and engaging performances, but Ray’s debut feature is the one whose impact I still find hard to articulate.

One such moment was when I saw Pather Panchali around five years ago at the MAMI Film Festival. It was a fantastic print from the Criterion collection, and that was a cinematic experience I was not prepared for. I would have to say that I do not think Ray has made a better film! The cinematic magic, the camerawork, the way the story washed over the viewer, makes me choose this film over the rest of the trilogy.

Nayak, Pratidwandi, Jalsaghar and Kapurush/Mahapurush are the other films from Ray’s collection that truly impressed me. I am not very adept at analysing what exactly make these films stand out in my eyes. I was drawn to the simplicity of the storytelling and in the case of Nayak, to the charming persona of Uttam Kumar. Pratidwandi is another gem, which is very underrated when compared to some of Ray’s more celebrated works. It has a certain rage that makes it unique among his films, and the themes it explores are relevant today, fifty years after it was made. The Ray film I am very curious about is Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, but I am waiting for a good print before I see it.

In Ray’s case, we have a body of work, and then we have adoring fandom and tomes of critical analysis. Being a filmmaker, I wonder about how he would react to both the unquestioning deification as well as the relentless scrutiny of the film school gang. My guess is that it he would be supremely unaffected by both. The realm of experience was what interested him, not the realm of opinions. The process of learning new things and the universe he occupied are what piqued his curiosity, not armchair activities like analysis and criticism.

I recently read a piece that claimed that my recent film, like Ray’s films, were made with the aim of attracting the West. I was at first flattered at being clubbed with the maestro and then, upon further thought, I wanted to respond by requesting the critic to say what he wanted to about me but to not sully Ray’s work with this silly allegation.

Part of this allegation comes from the persona of Ray. His clipped accent and style of speaking are seen as proof of his affluent upbringing. What they do not acknowledge is the amount of work he did, from composing music, to writing, to filmmaking. He made his films when India was a young democracy with limited resources, and his films still show us that world in a way that gives us perspective to those times. While pointing to his affluence and the exposure that came with it, nobody acknowledges what he created with that privilege.

Ray… made his films when India was a young democracy with limited resources, and his films still show us that world in a way that gives us perspective to those times. While pointing to his affluence and the exposure that came with it, nobody acknowledges what he created with that privilege.

Ray was excited by what he saw, be it the Imambara in Lucknow or the sleight-of-hand of a magician. He was driven by a thirst to know more about new places, different people and that is what influenced his stories and his cinema.

If his films were indeed not Indian enough and were made for the West, how did it get the warm and admiring acknowledgement of Akira Kurosawa? How are we still speaking about him and his cinema? It is telling that his films have been restored abroad and thanks to that, a new generation can enjoy his work. If these critics and commentators did indeed get to know Ray only after he was admired in the West, it speaks more about them than about Ray.

Such is Ray’s relevance that we still have new books published on him, and every young director (yours truly included!) is feted as the ‘next Satyajit Ray.’ When a man becomes an institution, his shadow is all-pervading and all who come in his wake are compared to him. Ray casts such a shadow on Indian cinema. We still debate the merit of other filmmakers by comparing them to him – Ray versus Ghatak, for example – and we still are looking for a new avatar among each generation of filmmakers.

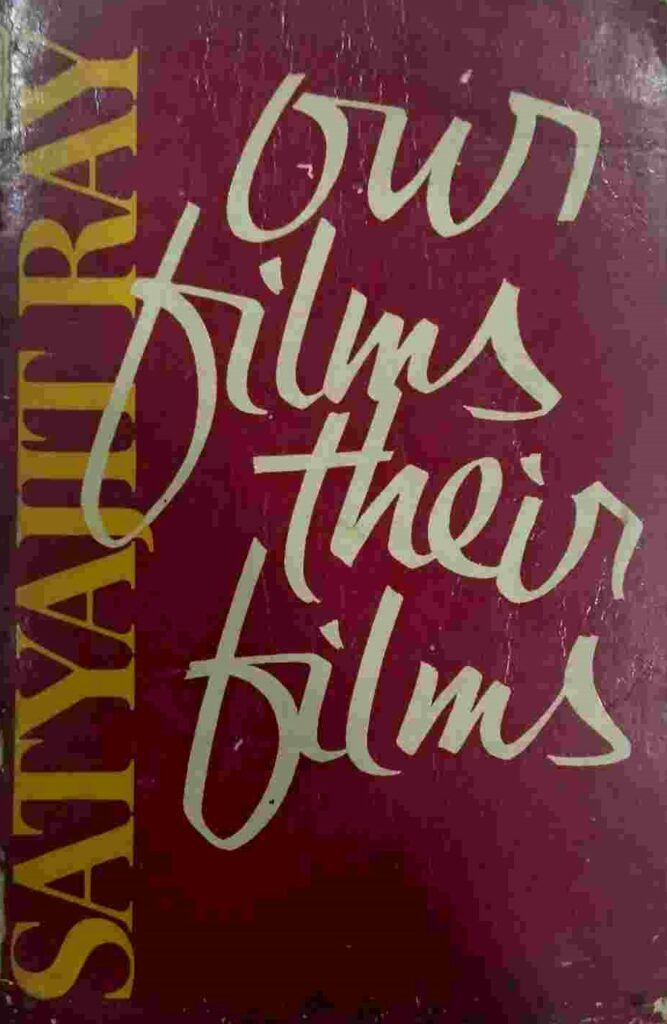

I started by mentioning Ray’s books and would like to conclude with another breakthrough moment that he is responsible for. I read his book Our Films, Their Films and was staggered by the insight and wisdom in the book. All the marginal wisdom I have gleaned after eight-nine years of filmmaking would have been mine, if I had read it earlier. Along with Speaking Films, they show the world of films with an unerring accuracy that would benefit any aspiring filmmaker.