My love for India dates back to when I was a young boy. I met many players from India in the juniors tournament and remember playing Surya Shekhar Ganguly in the under-10 tournament way back in 1992. We later became friends. But the fact is back then, India seemed so far and exotic, even though there are many commonalities, like the root language of Sanskrit and Armenian being the same. India seemed like an unusual, mesmerizing place. In my late teens, I was more ready to delve deeper into this culture. That is how I discovered the magic of Satyajit Ray.

I was nineteen when I came for a tournament to India. I was in Goa and I could tell this was a strange place – an amalgamation of the Western on one hand, and authentic, deeply Indian traditions on the other. I started getting drawn in firstly with music – Pandit Ravi Shankar was the first person I heard, then I got to know Nikhil Banerjee. Soon after, I discovered all the greats. I discovered the philosophy behind the music, which was deeply spiritual. As a young boy in the former Soviet Union, I had read Rabindranath Tagore’s works, as he was immensely popular there as well.

In the West, people do not know the depth of Indian cinema. They only identify it with the Bollywood fare of dancing and singing. However, if one delves deeper, there are gems to be found, none more brilliant than Satyajit Ray.

I am very interested in cinema, and follow Asian cinema, particularly Japanese cinema. I am a huge admirer of the works of Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu and many others of the period from the 1930s to 1950s. I like Akira Kurosawa as well, but one big difference is that in Ozu’s and Mizoguchi’s films, you see a lot of Japanese culture. I have seen all the films of these two directors, and their mastery over the medium is such that they suck you into their cinematic worlds. For me, the issue with Kurosawa’s films is that they feel Western. They are great, powerful, almost muscular films, but the authenticity I look for is more remarkable in the films of his great compatriots.

It is this authenticity that drew me to the films of Satyajit Ray. Because he, too, is telling the story of his people. He is not really trying to please the audience. He is not telling the story of Apu to make you happy, for example. When you see Pather Panchali you see the old aunt and you feel the mother (Sarbajaya) is treating her very unfairly. She seems to be pushing the old woman away and you feel the situation is completely inhumane. But gradually, you see the circumstances and you realise that poverty has made life a struggle for survival for the mother. If the director had wanted to make his audience happy, the mother would have a change of heart, but Ray is committed to honesty, even when the story and images are negative. You can see the context. The actors, too, add to the classic by not overplaying or over-dramatizing their emotions. In the same film, you feel that the father is useless, leaving his children to die. But we are immersed in the story now and are aware that he too is just trying to earn for his family. He is an educated Brahmin who wants to feed his family. He is in a poor place and his services have no value there, so he has to travel. Nobody is to blame for Durga’s death, but the death itself is unbearably tragic.

The director is not treating viewers as children, simply telling the story without melodrama. He lets the viewer into a real world, where he or she can understand the characters. This natural feel is a true skill that unites the great directors of Asia. The authentic emotions and settings are truly priceless.

In Aparajito and Apur Sansar, you see negative traits in Apu. The traumatic experiences from his childhood have affected him, he cannot connect to the family. In one film he does not want to spend time with his mother or in the village anymore, and in the other, he does not want to meet his son anymore.

The director is not treating viewers as children, simply telling the story without melodrama. He lets the viewer into a real world, where he or she can understand the characters. This natural feel is a true skill that unites the great directors of Asia. The authentic emotions and settings are truly priceless.

While I truly think that the (Apu) Trilogy is a classic, the movie most people rather predictably ask me about is The Chess Players (Shatranj Ke Khilari). To be honest, I have not seen the film, because when I saw the costumes and the settings, it simply made me feel distanced from it. I know it is Ray’s most lavishly mounted film, but it did not draw me in, even though I am a chess player!

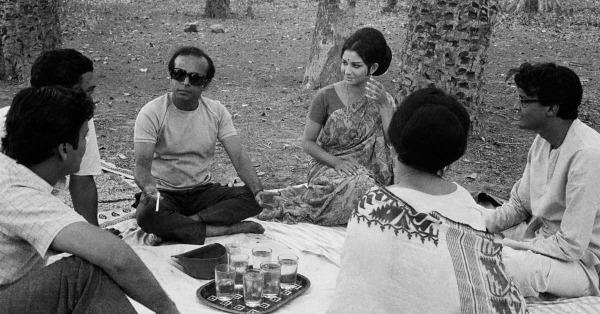

The other film I really enjoyed was Days and Nights in the Forest (Aranyer Din Ratri), because it is very authentic to the way young men and women behave. The submissiveness of the girl in the memory game, the yearning for love in the young widow, all of this shown so wonderfully. The desire the widow feels distances the man from her, even though he is deeply attracted to her. He has to reject her because he feels there is something ethically wrong in forging a relationship with a widow.

I also connect a lot as an Armenian. Like the young men in the film, they are cocky, ambitious and feel no qualms about using corruption and the system. They are nice guys but they are callous too, and I have seen such people back home as well. In the film, the guard’s wife is sick, but these youngsters do not care enough to do anything about it. They do not even care if he gets fired or not. It also shows tribal cultures in India, effectively using the literary/cinematic trope of the carnival to highlight the circumstances of the characters.

I have seen around a dozen of Ray’s films and look forward to discovering more films by him, like Charulata. The challenge until recently was obtaining good prints. Criterion has done some restoration, so that Ray’s remarkable filmography is accessible to admirers across the globe.

I do understand that Ray is a great director for Indians who love him, but they know the world he shows quite well. For foreigners, Ray’s films are fascinating in an entirely different, dare I say, more powerful way. For me, seeing today’s India with so many people and comparing it to Ray’s films and the lack of industry and urbanisation, you realise the changes in the intervening decades. Today’s India is perhaps more reason to watch Ray’s films, it shows you the country’s past and the journey India has taken. Like in classical music, Asia’s great filmmakers show the soul and spirit of their respective countries.