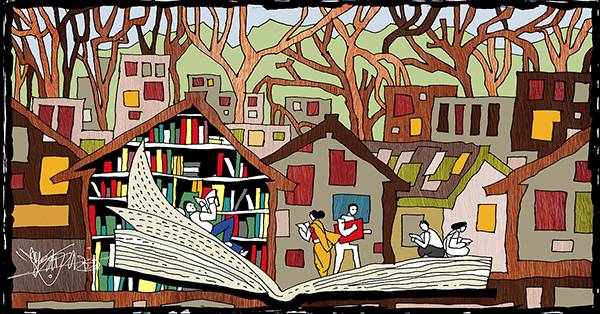

The Magic of Small-Town Bookstores

That bookstores were integral to the ‘civilised’ life would perhaps have never occurred to me, or emphasised in the manner it has been, had it not been for the celebration of the bookstore on social media. Celebration soon led to its fetishisation, as is the norm on social media, so much so that access to a bookstore began to be equated with education. The names would circulate: Shakespeare & Company, the Strand, Bahrisons, The Bookshop at Jor Bagh, Kitabkhana, and so on. A glamour attached to their names, to these habitats, and it was this that was emphasised repeatedly – it was linked to a superior reading experience, and, consequently, to a more cultured life. It annoyed me sometimes. There were no such bookstores in Northern Bengal as I imagine there aren’t in many other parts of India. Did it imply a lack in the life of its residents?

In the 1980s and 90s, the only ‘bookstore’ in Siliguri from where we could buy English language books – novels and poetry collections – was a place called ‘Modern Agencies’. It sold refrigerators and other electrical devices, even typewriters, and a host of things that took over the shop but whose identities are now a blur in my memory. The few shelves that stood at the corner of the shop are not. For it was there that I encountered the writers who were not on my school or college syllabus – these neat editions stood there for years, perhaps even decades, for I never met anyone who bought them. I remember reading Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate standing between these bookshelves, hoping not to be scolded or caught for reading for free. Book-selling, like book-buying, was clearly not on anyone’s mind in this shop. It was a giveaway sign about the culture of reading in the town.

In the 1980s and 90s, the only ‘bookstore’ in Siliguri from where we could buy English language books – novels and poetry collections – was a place called ‘Modern Agencies’. It sold refrigerators and other electrical devices, even typewriters, and a host of things that took over the shop but whose identities are now a blur in my memory. The few shelves that stood at the corner of the shop are not….I remember reading Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate standing between these bookshelves, hoping not to be scolded or caught for reading for free.

Bangla books were available in Collegepara. Though they stood together as a cluster of shops, the residents of the town referred to them as ‘Bani Library’, the name of one of the bookshops. I cannot exactly say whether this was because it might have been the eldest among them. They sold textbooks on the school and college syllabus, but, once in a while – and it was more common in the last century – one could meet Baudelaire in Buddhadeva Bose’s translation or a history of the tea gardens in north Bengal or even the latest issue of a locally published Bangla little magazine. The shops looked no different from pharmacies – books were kept out of the reach of customers, but it wasn’t that alone. The men – and yes, there were no women selling books in these shops – behaved like pharmacists selling OTC drugs. Like one could simply say ‘Headache’ and a strip of Saridon would emerge as cure, one could go to Bani Library and say ‘English Honours Paper I’ – a Long or Compton-Rickett or David Daiches would be supplied as diagnosis and medicine.

The idea of sitting in a bookstore, reading, drinking coffee, writing, all of this was unavailable to our small-town imagination. Neither Modern Agencies nor Bani Library had any seating space.

The first time I felt that a bookshop could be a space for adda was when I went to a place called ‘Books’ in Siliguri’s Vivekananda Mini-market. Hidden – and I mean that it was hidden – behind shops selling clothes, food, medicines, toys, and photocopiers, this shop was owned by Tapan Majumdar. Someone at the shop – a student of Bangla literature – told me that he was the Bengali writer Samaresh Majumdar’s brother. Tapan-da is an extraordinary person – gentle and welcoming, he encouraged his customers to speak to each other, to discover books in these conversations. And he always managed to get us the books we needed – from Calcutta. When I think of the teachers I’ve had in my life, I think of the invisible ones – Tapan-da was one of them.

Arnab – whose contact details are saved on my phone as ‘Arnab Books’ – stretched that idea to give to this town what it had never really had: a library. He called it a bookshop, and that was what it was, but as students came out of Gate No. 3 of the North Bengal University campus, they entered Ane Books, where Arnab often gave them a bottle of water. Students rarely have the money to buy all the books they want or need. And so, Arnab stayed away as they browsed through books and chatted. He sometimes let them photocopy portions they needed to pass examinations; he let them borrow books for a few days; he let students return to the book with friends for company, eavesdropping on their discussions. In his shop were books that were mostly out of syllabus – he would push a new book into their hand and say, ‘Eta dekho’, take a look. He introduced students to more writers than the syllabus and its teachers did.

Arnab – I do not mention his surname because most of us who were fond of him did not know it – is now gone. The death of people often causes their close ones a feeling of homelessness. Arnab’s going away, loved as he was, has left this town and its suburbs feeling bookless.

Illustration by Suvamoy Mitra