Darjeeling Through ‘Ritu Vichar’

Given the nature of our curriculum, where we know more about the history of Europe than we do about the places we live in, I shouldn’t have been surprised that I knew nothing about Lekhnath Paudyal. A year or two into my life as a teacher in Darjeeling, one of my students mentioned Ritu Vichar. Soon after, I was with him in Chowkbazar, trying to get myself a copy from one of the few tiny bookstores in the town. The unremarkable bluish cover made me sad – it was a manifestation of the history of neglect of which people like me and the culture I was coming from were complicit.

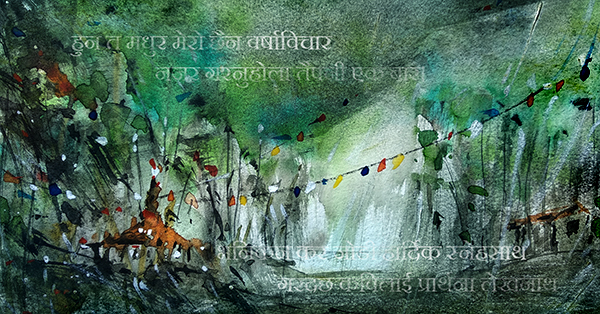

A collection of poems about the seasons, I began reading them during the rainy season. The rains seem to be the longest season in the Darjeeling hills, and often in North Bengal. Umbrellas and tin roofs and the sound of feet and shoes on rain-oozing streets and squishy mud – that is the background to conversations for half of the year. The human voice must compete with the sound of rain all the time – one becomes a singer without knowing it, for the rains are an accompanist. It was against the background of such a sound, then, that I began reading Ritu Vichar.

The rains seem to be the longest season in the Darjeeling hills, and often in North Bengal. Umbrellas and tin roofs and the sound of feet and shoes on rain-oozing streets and squishy mud – that is the background to conversations for half of the year. The human voice must compete with the sound of rain all the time – one becomes a singer without knowing it, for the rains are an accompanist. It was against the background of such a sound, then, that I began reading Ritu Vichar.

I read aloud, though for no particular reason. My sole listener was Arati Singh. She cooked for us and scolded us, doing both with great affection and attachment. Suddenly she screamed: ‘Ritu Vichar!’ I am ashamed to say that her recognition of the poem surprised me, so conditioned was I to ascribing illiteracy to house help and other workers from the unorganised sector. Arati knew some of the lines by heart from school, and I heard the sound of the Nepali words come together with the rain as I sat on the tiny balcony of my rented flat overlooking Happy Valley.

Lekhnath Paudyal, considered to be the architect of modern Nepali literature, is often spoken of in shorthand as ‘kabi shiromani’. His name, of course, means the god (‘nath’) of writing (‘lekh’). A classicist whose poems owe to his understanding of Sanskrit poetics, Paudyal’s influence on the next generation of poets has been minimal. I never heard him being mentioned by the few Nepali poets I knew from university or in Darjeeling. And hence the greater surprise of his place in Arati’s memory. Paudyal’s first major composition was ‘Varsha Vichara’ (A Reflection on the Rains) in 1909.

हुन त मधुर मेरो छैन वर्षाविचार

नजर गरनुहोला तैपनी एक बार।

भनिकन कर जोडी हार्दिक स्नेहसाथ

गरदछ कविलाई प्रार्थना लेखनाथ

A little less than two hundred years before Paudyal, the Scottish poet James Thomson wrote a similar series called The Seasons. Thomson’s work had an impact on many of his contemporaries and those who came immediately after, including Joshua Reynolds and J M W Turner. He brought blank verse to his experience of the seasons, borrowing and then extending the Miltonian blank verse. Critics have not always been kind to him, as they have not been to Paudyal. Both have been faulted for their devotion to a version of classicism that has brought a kind of stiffness to their writing of the seasons.

I told Arati about Thomson and The Seasons. He, too, like Paudyal was writing poems about the seasons from the mountains. The critic Raymond Dexter Havens’s criticism against Thomson would hold for Paudyal too – that he avoided ‘calling things by their right names and speaking simply, directly, and naturally’. Why did they do that, I wondered aloud. Arati, a woman of extraordinary wit who had not let her lack of formal education get in the way of her experience of life and art, was quick to respond – ‘Some things cannot be said directly, such is the nature of life: we find it hard to even say that we are going to shit, we say “toilet”.’

The critic Raymond Dexter Havens’s criticism against Thomson would hold for Paudyal too – that he avoided ‘calling things by their right names and speaking simply, directly, and naturally’. Why did they do that, I wondered aloud.

I read Ritu Vichar from time to time, and occasionally found myself thinking of Kalidasa, or the poems about the seasons attributed to him. For most of the teaching year – March to mid-December – it was the rains that drove our life. The chronic problem of water shortage before the rains made us wait for a time when the tanks and reservoirs would fill up naturally; when the rains came, we wanted it to leave. Even when there was no rain, I heard it, like Kalidasa had: ‘The rain advances like a king/ In awful majesty’.

One day, Arati asked me about the seasons in the poems, both Paudyal’s and Thomson’s. I took the opportunity to tell her about the six-season cantos common to such poems. Arati shook her head in disapproval – why hadn’t Paudyal written about the most important season in Darjeeling?

I looked at her, slightly confused. Had I missed any of the seasons from Ritu Vichar?

‘Tourist Season,’ she said, laughing, ‘The most important season in Darjeeling!’