Gujarat jachchi, undhiyu-i khabo. Biryani khunjbo naki? (In Gujarat, undhiyu is what we will have. Who looks for biryani there?”) said my colleague Vikram Iyengar, on our first day in Ahmedabad on work. Well, of course not. My last Ahmedabad trip had been rich in ghee-drenched rotlas, bhakris, undhiyu, sweet puran polis and snack-time bites of soft dhoklas, flavourful theplas and crisp fafdas. Armed with these memories, and some recommendations, we were ready for some Amdavadi food.

But our very first meal turned our expectations, rather our ingrained assumptions, upside down. A hot Ahmedabad afternoon, a missed lunch, a clarification to Kushal Batunge, the local photographer who was happily playing the role of our guide that we were non-vegetarian and we found ourselves bundled into an auto, heading towards a meal of non-veg samosas. Our destination was Famous Samosa – in the middle of the old city, right across from St. Xavier’s Collegiate School.

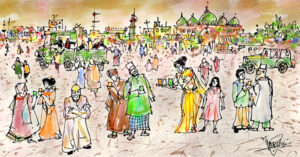

A long, narrow space with granite-topped tables and wooden benches, Famous Samosa was reminiscent of old Mughlai eateries such as Aliah in Kolkata. Every table was full. Customers ranged from lunch-break lawyers from the High Court next door to cabbies and the occasional tourist.

Famous Samosa serves only two items – beef pakora and beef samosa. Orders are by weight, and one can order a mix as well. Since we had missed lunch, Kushal asked for pavs. In minutes, we were served 500 grams of pakoras and samosas on a shiny steel plate. Another plate, this time with our pavs, was banged down and for quite some time after that, there was no conversation at our table.

The food deserved – and received – our complete attention. The samosas, with their delicate, phyllo-thin shells bursting with a coriander and chilli-spiced filling, were delicious. The pakoras were like meatballs, but with a slight crunch. The pavs were quite unlike the usual ones in shape, taste or texture. Round and pillowy, with the Gujarati penchant for sugar evident in the sweet aftertaste, they were an unusual but wonderful accompaniment to scoop up the pakoras. A wave of the hand and another full plate was ready, before we had finished our first. The soundtrack to our meal was continuous cries of “trann-sau” “paanch-sau” (300 grams, 500 grams) and the rapid-fire, staccato beat of plates being set down on tables.

Delicious as the food was, the speed at which it was being consumed was quite something to see. At a guesstimate, easily 8-10 kilos of meat-filled goodness were being consumed every 5-7 minutes. This was confirmed by Jabir Sheikh, the proprietor of the eatery, who said, “On an average day, we sell anywhere between 125-150 kilos –it is a tasty, inexpensive meal served hot and fast. These are working people and don’t have time to eat at great leisure.”

While my taste-buds were happy to contribute to the day’s 150 kilos, I couldn’t get rid of a nebulous anxiety. What if a mob came in, ready to lynch us beef-eaters? What if the police raided the place and arrested those found guilty of gorging on this holiest of holies? After all, Gujarat is ferociously shaakahari. Or so I thought. But, as further research revealed, the numbers tell quite a different story.

It seems that the shaakahari Gujarat that exists in our minds is just that – a story in our minds. And, of course, one of Chief Minister Vijay Rupani’s dearest wishes. But, to realise this dream, the Chief Minister will have to convert a substantial chunk of the state’s population to vegetarianism. How substantial? You might be as surprised as we were.

According to the Sample Registration System Baseline Survey 2014, carried out by the Census of India, almost 40 per cent of Gujarat’s population is non-vegetarian. This is significantly higher than Punjab (around 28 per cent) and Rajasthan (around 27). Despite these numbers, there is a distinct disgust directed at meat eaters in Gujarat’s culture. Along with an undeniable, uncomfortable division by religion, caste and creed.

Raw meat is available sparsely in so-called Hindu areas and is identified as “Muslim” food, even though meat eaters are found in each and every region of the state and mostly belong to the OBC, Dalit, Rajput and tribal communities. Non-vegetarian food is not readily available anywhere in ‘New’ Ahmedabad – the Ahmedabad of the affluent, of the vaunted riverfront, the one we see on our TV screens. Ahmedabad, in fact, has the dubious distinction of being home to the first vegetarian outlet of Pizza Hut in the world. In areas dominated by the Jain community, public eating places make pizzas and dal makhani without onion. In Muslim-dense pockets, some eateries do operate. But, during the holy Paryushan period of the Jains, slaughterhouses are shut down. This practice apparently originated in history. It is said that after receiving a delegation of Jain monks from Gujarat, Emperor Akbar banned animal slaughter on Mahavir Jayanti and during the holy months of Chaturmas. Historically true or not, the practice continues to this day, with slaughterhouses and eateries forced to down their shutters. This, even though the Jain community is a minority – less than one per cent of the population – in the state.

But, what about that 40 per cent for whom meat is a part of their regular diet? Not just fish, chicken or mutton, but beef as well. Given that beef is without doubt the cheapest, doesn’t this affect the nutritional intake of those who cannot afford costlier meats?

It seems that the shaakahari Gujarat that exists in our minds is just that – a story in our minds. And, of course, one of Chief Minister Vijay Rupani’s dearest wishes. But, to realise this dream, the Chief Minister will have to convert a substantial chunk of the state’s population to vegetarianism. How substantial? You might be as surprised as we were.

Chetna Rathor, like Kushal, belongs to the Chhara community (classified as OBC) says, “Our food habits, like other nomadic people, have developed by hunting and gathering. Whichever meat was available, was put in the pot with whatever vegetables and herbs could be procured, and cooked over a wood fire. With people settling down in urban areas, we have refrigerators, pressure cookers and gas stoves today but our food habits remain the same. But as a subaltern community, what we need or want is not only considered unimportant, these have been reasons to stigmatise or criminalise us even further.”

Talking of crimes, what exactly are the laws? Slaughter of cow, calf, bull and bullock; transport, sale of their meat is banned in Gujarat, with a punishment of Rs 50,000 as a fine. The punishment for slaughter of cows has been increased to life imprisonment. In a statement, the Director of Animal Husbandry A. J. Kachhi Patel had said, “We do not allow slaughter of cows at all. There is no export of beef. There is controlled buffalo slaughter, but only to cater to local consumption.”

So, there is an acceptance of the fact of local consumption, however grudging? Yes. But ‘local consumption’ patterns have had to adapt to the ideology of the party that has been in power for the last 23 years. Famous Samosa serves carabeef, not beef. Carabeef– or buffalo meat – is allowed, but very few slaughterhouses have licences.

But, does this in any way lessen meat-consumption? How can it, asks film director, theatre person and food lover Dakxin Bajrange while sharing with us his dabba of rotla, sabji and mutton kanji, a curried preparation specific to the Chharas. Says he, “Just as bootlegging increases with prohibition, fresh raw meat from unlicensed slaughterhouses finds its way easily to homes and dhabas across the state. Fry centres and tawas continue to sell chicken and mutton dana, biryani and mutton samosas. And continue to see brisk patronage by ALL communities, even if not openly.”

This is confirmed by Jabir Sheikh. “Eighty per cent of our local customers are non-Muslims. There is a large meat-eating, Gujarati-speaking population in the state. But, you will only find them and the eateries that cater to their food habits in the old city. Business visitors and tourists who come to Ahmedabad rarely come this side of the Sabarmati. In west Ahmedabad, apart from fancy hotels and a few restaurants, non-veg food is rare. And it is completely absent from the streets,” he says.

Chetna continues, “Why just our daily food habits – our festivals are incomplete without meat and alcohol. Not just the celebration but in the actual, ritual sense of completion. For instance, during Holi, the community gathers in the evening to cook whole goats over bonfires. That is a must for the year to go well. We call it vaari. So, slaughterhouses not being allowed to function makes it difficult for us.”

Kushal chips in with a mischievous “Oh we manage, not to worry. But, more ‘obedient’ citizens have a problem!” clearly laughing up his sleeve at society’s ‘classification’ of their community as‘habitual offenders’. But, as Dakxin points out, slaughterhouses shutting down when a minority community has its festival, despite the fact that this impacts a significantly larger section of the state’s population, is telling. Would this practice ever be labelled ‘minority appeasement’? Everyone knows the answer is no, but not just because the Jain community is moneyed and influential.

Take away a people’s food – not just their daily meals but the ways, means and meats to fulfil their food habits – and you slowly but inexorably chip away at their very identity. This ‘chipping away’ ties in with not just the CM’s green dreams, but the ruling dispensation’s not-at-all hidden agenda.

Dishes such as tetar ni kadhi (partridge curry), boklo no kalejo (liver of he-goat) and mutton nu shaak were as much a part of Gujarati cuisine as undhiyu and shrikhand. These have disappeared from the public palate. The ban on hunting, the unavailability of people who can cook these are all reasons. But the most overriding reason is the miasma of disapproval of non-vegetarian food habits that permeates the air in Gujarat. And always, always there is the other pervasive narrative that peddles the idea of a vegetarian Gujarat.

While the beef samosas on the first day made us acknowledge our assumptions, and the mutton kanji meal on the last reinforced what we had learnt about the unacknowledged food of Gujarat’s subaltern communities, the days in between threw up revelations and lessons of their own. On our second day, when we asked Pinakin, a member of Darpana Academy of Performing Arts, for food recommendations, his response left us stumped. “Had Mughlai food yet? No? You cannot come to Ahmedabad and not have our Mughlai food.” Our reaction was one of cognitive dissonance. We were in Ahmedabad, weren’t we? Not in Lucknow or Delhi!

But that emphatic statement brought to mind long-forgotten history lessons – evidence of a mosque on India’s western sea coast had been found as far back as 8 CE; the Gujarat Sultanate had reigned here for over 200 years before becoming part of the Mughal Empire under Akbar. Gujarat’s Islamic connection, thus, ran deep and strong and so, Mughlai food was a must.

Unknowingly, our non-veg food journey in Ahmedabad had started with a place with direct links to the olden days. Jabir Sheikh belongs to a ‘shahi parivar’, one of the khandani khansama families whose roots go back to the Mughal Sultanate. He says, “What we serve at the eateries is very simple, fast food of sorts. Come and eat with us at home – we will feed you dum biryani, kofte, seekh kabab, mutton korma, dana chicken like you have never had before.” Promising to hold him to his invitation in safer times, we set off into the old city with his recommendations. A plate of dana at one cart, seekh kababs at another, and dinner of delicious sheermals and a murg mussalam good enough to rival Kareem’s was our dinner on our last night in Ahmedabad.

Despite the night curfew that started at 9pm and the Section 144 that is always in effect in Gujarat, we had managed a Gujarati thali, basic and fancy khichdis as well as rushed meals of khaman dhokla and fafda. Every bite of those well-known Gujarati staples had been delicious.

But, it was in the chaotic streets of old Ahmedabad, redolent with the aroma of chicken dana being fried, kababs being grilled and handis of biryani on dum, that we found more than just delicious food. Food as oppression, food as survival and, most important, food as identity were the stories that emanated from the kitchens and eateries of less privileged Ahmedabad.

It is clear that Ahmedabad and indeed Gujarat’s non-vegetarian cuisine is alive and thriving, despite the shakahaari agenda. Yes, the availability of meat – raw or cooked – has been constrained and constricted within certain geographical coordinates. But, with constriction also comes focus. And Old Ahmedabad is a focussed centre of all things distinct, distinctive and unapologetic. Not just in terms of its huge range of food but in terms of a myriad distinct identities.

And as happens with centres, its influence seems to be spreading in ripples, with younger Gujaratis becoming quite game for a meal of game. Maybe, some day in the not-so-distant future, what one Gujarati eats will not be seen to offend the God another Gujarati prays to. Maybe, some day it will be food that will smudge, if not outright obliterate, these divides. Both, of the past and the present.