Of course, this duplication can be very productive. The catalogue of Homer-like or Sophocles-like García Márquez will continue to be sold and bet for and against in the global markets of the literary industry. And the blinding shine of his simulated deified figure will continue to legitimise so-called ‘modern literary fiction’ written in the Spanish language as a simulated whole for all the time that can be calculated by the managers and accountants of editorial houses worldwide.

The same goes for the parasitic (humourless, deadly serious) nation-state/market sucking out the life of its humble producers, which it otherwise kills, abandons to death and plague, or sends into forced exile after accusing them of terrorism, of guerrilla sympathies, as it did with the actual García Márquez. In other words, the apotheosis of García Márquez is but the other side, the masking and simulation, of the cleavages and self-contradictions within this all too human, humble and secular basis.

That is the ‘civil’ war and conflict that his work endeavoured to make sense of and illuminate. Ironically and humorously. To help our own memory-work in the present and for the future. So that we too could mock and laugh at the faux visage of our incompetent bureaucratic managers, our humourless clownish rulers, premiers, newspaper-and-reality TV celebrities-turned ‘organic intellectuals’, presidents and CEOs pretending to be heroes, cultural geniuses or tyrants, and, in any case, narcissists appearing to themselves and to the mass audiences of our everyday tragedies-turned-farce as if they were ‘masters of the universe.’

That laughter is the universal mode of dissent, and a much better orientation for action than the pessimism of the ‘paradigm of disillusion’. The former is like air and lighthouses. Illuminating. Invigorating. It gives us air, and in this day and age of pandemics we know how important it is to breathe or not to breathe. So is the hard work of García Márquez, humble producer. The latter, the paradigm of disillusion, is instead like the lanterns of wreckers in the North Sea trying to lure ships aground so as to loot them. It is destructive. It produces the void. Which is another way of saying that it produces nothing, even if it can be very productive.

VII

This is how we can best read the Colombian writer today. As a producer entering into an alliance with his strange and stranger readers, not familiar kin but other kin, so as to stay with the problem and produce a different future. His work illuminates the present like lighthouses. Helping us see and laugh.

This is how to best comprehend his ironic remark that the only mythical/tragic creature invented in the Americas is the tyrant. But let us add that the tyrant nowadays is less like Oedipus Tyrannus and more like its farcical simulation. A simulation of itself and thus just another commodity to be disposed of and consumed as convenient.

The more relevant myth here is that of Narcissus. But only if his look and reflected image is taken up as the voyeuristic gaze of our iPhones and the garbage images that populate the technosphere and (mis)inform the algorithms of our systems of auto-pilot governance.

Of course, the tyrant also learns. They have now let go of their military uniforms, the pomp and circumstance of martial parades, their dark shades and macho moustaches. They wear grey suits and business-like attire and use business-like language. They speak in acronyms and parade before the cameras all manner of expert surveyors and metrics. They have become masters, if not of the universe, at least of the farcical performance before the camera and of making fools of themselves. But they cannot make us laugh. They make us die.

VIII

Understand this. Productive literature under the paradigm of disillusion is part and parcel of a more general attempt to erase or cancel the mass utopias of the East and the West that were central to the history of the last century. We should count García Márquez’s hard work as an aspect of such utopian vision and drive. Therefore, as inimical to the seemingly ongoing slow cancellation of the future.

But if so, the matter in question, and of the question concerning how to read García Márquez today, is memory. And at least in this respect, García Márquez’s work may be more relevant now than it was back then, during the glory days of the so-called Latin American ‘boom’ and ‘magical realism’ (that misnomer, the result of an ad campaign or a navigating error).

More relevant, that is, than the normalising paradigm of current literature in the Spanish language. As such, it must be salvaged from its ‘tragic’ destiny amidst the ruins of modern literary fiction. To clarify and be precise, if the matter in question is memory, not only as more efficient or productive but in terms of the hard work of memory producing a different future (that is, in terms of the social and political institutions that bridge our lived experience of reality with our imagination of it), then it turns out that García Márquez treatment of the plague in his work, and in particular the plague of oblivion that features so prominently in One Hundred Years of Solitude is crucial for us today.

IX

Let’s explain further. Beverley unpacks the idea of the ‘paradigm of disillusion’, which so-called ‘vargasllosism’ would be an example of, by way of Bill Clinton’s famous remark that how one views the Sixties and the Seventies remains the basic fault line in American culture, providing the best measure of whether one votes Republican or Democrat. This in order to suggest that there’s a relation between how one thinks about armed struggle or revolution in the Americas and how one thinks about ‘the possibilities of the new [and now not-so-new] governments of the [so-called] marea rosada’, or the Pink Tide of progressive activist governments that swept through the Americas during the first decade of this century, which I wrote about in What If Latin America Ruled the World? But also, to add to Beverely’s schema, to make sense out of the rise of reactionary post-Fascisms in more recent years.

What would be the point of suggesting this kind of relation vis-a-vis the theme of historical memory as either merely productive, or else, as producing of the future? Simple. If you see armed struggle in particular and socialist revolution (including its other, reformist, strategy) as equally guilty, as mistaken and as corrupt as its fascist opposite number during the last century, then chances are you would be not just extremely sceptical about the Pink Tide of reformist governments of the left in the Americas or the BRICS alliance that also included India this century, in particular. And call yourself a temperate or moderate ‘centrist’. But also, in general, deeply sceptical of any kind of forward-oriented possibility for life after Capitalism now or in the future.

Well, this kind of widespread hopelessness, which erases the utopias of the past and threatens to cancel the future is the best climate in which the poisonous, plague-like derivative fascisms of our time can grow and thrive. If so, what is at stake here, in our comparison between two ways of bridging the gap between reality and the imagination via memory and production, or creative work, is something a lot more important. It is not whether you ascribe to this or that ideology, or none (which, by the way, is also an ideological identification). Instead, what is at stake here is a material question. The matter of time and history. Whether we see the hard work of memory and its humble producers as itself producing the future. Or else, if we see such work as merely productive, tool-like and disposable. If the former, then what is at stake in the intersection between artistic practices and ethical-institutional discourses is history itself. Not the past but the possibility of history to come. If the latter, the future is cancelled or foreclosed.

Small wonder then, the latter choice can be identified as melancholic or to be more precise as an eternal look and pessimism. That’s precisely what Beverley means when he refers to the literary critic Beatriz Salo’s comments in the context of the Kirchner government in Argentina, and, by extension, to someone like Mario Vargas Llosa plays when he performs and pretends in the role of political thinker or political theorist. Or rather, as opinion-settler. They all settle and establish as (authorised) opinion the eternal look at pessimism. And, conversely, disavow all other perspectives. They read history in the sense that Thomas Carlyle called ‘visuality’, from above, as if from a Mountain of Vision. This is history of and for heroes. For the victors in battle, or the (restorative) Greek model of memory as aletheia.

This is history as a whole told in the register of tragedy. As inevitable fatality or Fortuna. A mistake from which there is no real escape. Perhaps only the kind of ‘second birth’ that supposedly comes from history repeating, learning from it and from the confession of our mistakes that, they say, would purge such mistakes.

Or, to use the language of the poetics and the philosophy of tragedy, from anagnorisis and catharsis, or retribution and cleansing.

X

Notice, however, that here we’re not talking just about sentiments or experience here, but also, or rather, about institutional attitudes.

I believe this is what is at stake in how we remember García Márquez. How we read him today and how we understand his relation to tragedy and hours.

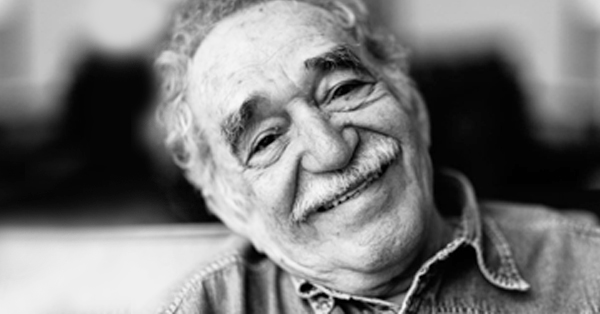

Of course, I am forcing a contrast between García Márquez and ‘vargasllosism’ in the shape of a provocation. As if they had ever engaged in a punching match. Unlike García Márquez, pro-Cuban and leftist, Vargas Llosa appeals to settled opinion as the more politically correct of the two, also a Nobel prize winner, and more in tune with the times: ultraliberal or libertarian, an exemplary instance of the paradigm of disillusion, an enemy of the ‘enemies of open society,’ or the ‘organic intellectual’ of El País de España and Hola magazines. Besides, the latter is alive. Gerald Martin would have said everything that can be said of Gabriel García Márquez in his excellent biography. We’re still waiting for his biography of Vargas Llosa.

So, what else can we say about García Márquez? Nothing. Something. A little thing. A humble thing. For instance, that he was a humble producer and can be best read today as such. For instance, we may ask if the ongoing plague allows us to read García Márquez, the producer, differently. There are those who have read in one of his phrases in La Hojarasca (‘I seem to have breathed in the first breath of the air that boils upon the dead, all that matter of doom that has destroyed Macondo’) the trace of the poetics and the philosophy of tragedy. So be it. From The Leaf Storm (La Hojarasca) to Oedipus Mayor (Edipo Alcalde), his 1950s fragment on anthropophagy and predation to his magnum opus One Hundred Years of Solitude, from Faulkner to Sophocles, García Márquez would have read Colombia’s permanent war in terms of the Greek tragedy.

In that reading, the problems of which we have already discussed, the plague would manifest the tragic fate of the hero turned tyrant. That mythological animal invented in the Americas. But then, our lived experience of the plague has manifested not so much the variegated cast of heroes or tyrants of the old problem of evil turned into the new problem of evil. Rather, something much humbler: that we are in the hands of incompetent bureaucrats and reality TV celebrities with nothing to say. Without ideas, elevated to the status of the thing by likes, tweets and duck-face images repeated over and over again on screens.

Neither they nor we learn from repeated history or catastrophe. We know so, but we refuse this knowledge and would prefer not to see, not to understand and run from the light as if to return to the comfort of the digital shadows performing on our digital retina-screen devices in the false security of our caves. No anagnorisis and no catharsis here. No redemptive revelation, no purge of negative emotions in the scene or confession. If so, the register of tragedy is no longer sufficient.

So, for the last time, how to read García Márquez today? To begin with, history does not repeat itself, and we do not necessarily learn from it. Neither the confession of the tyrant, nor his absence would suffice. And our situation is neither doom nor apocalypse. After all, the problem with apocalypse is that it is never apocalyptic enough. Something much more modest and material has destroyed Macondo. And it’s up to us to change it. We can’t wait for heroes or gods.