By the time World War II had started, an Indian National Army had been formed by the revolutionary Subhas Chandra Bose. Now Britain was under pressure from two very different Indian leaders. Its economy shattered by the costs of the war, Britain agreed to an early transfer of power.

But there was a price to pay for freedom. Partition.

I was a schoolboy, twelve years old, when the Indian flag went up on the flagpole on the playing field of my boarding school in Shimla. Down came the old Union Jack, familiar to us over the years.

There was excitement in the air. A new nation had been born, and we were a part of that birth, some two hundred boys of different faiths and backgrounds. In the pouring rain, we marched up to the Mall to join the parade and listen to speeches by an array of notables. Shimla had been the country’s summer capital, and Mountbatten, the Viceroy, was still in residence.

No television in those days, no internet, but Mr Nehru, now Prime Minister, had spoken to the nation over the radio, his speech a reflection of his knowledge of world affairs and his familiarity with the English language.

How we depended on the radio in those far-off days for news, for messages from our leaders, for commentaries on cricket matches played at home and abroad.

Melville de Mellow, our most celebrated newsreader and commentator, had been a student of our school. His familiar, booming voice brought us descriptions of parades, celebrations and disasters.

India had been divided. In their haste to ring the bells of freedom, our leaders had agreed to the partition of Bengal and Punjab on the basis of religion.

A massive displacement of populations had to take place and did take place amidst riots, mass killings and human tragedies. West and East Pakistan were created. Millions of Hindus and Sikhs were forced to leave their homes and flee to India; millions of Muslims fleeing to Pakistan suffered in much the same way. Murders and reprisals continued for days, weeks, and months.

Britain had always described India as the Jewel in the Crown. Now the Jewel had been smashed to pieces. Mountbatten had been under pressure from the British government to hasten the process of Independence, and the result had been terrifying for a time at least…

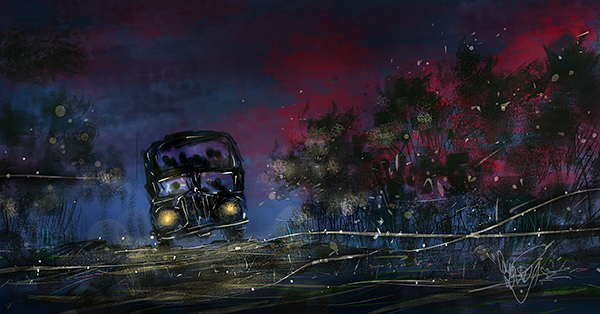

Our school was divided too, but not from communal strife. One-third of our boys came from homes in Lahore and other cities of what was now Pakistan. The school itself came under threat from violent groups in the bazaar. In the middle of the night, all our Muslim boys were bundled into Army trucks and driven to the borders of their new country. They arrived safely, but I was never to see them again.

Britain had always described India as the Jewel in the Crown. Now the Jewel had been smashed to pieces. Mountbatten had been under pressure from the British government to hasten the process of Independence, and the result had been terrifying for a time at least…

Our school was divided too, but not from communal strife. One-third of our boys came from homes in Lahore and other cities of what was now Pakistan. The school itself came under threat from violent groups in the bazaar. In the middle of the night, all our Muslim boys were bundled into Army trucks and driven to the borders of their new country. They arrived safely, but I was never to see them again.

When I came home to Dehradun that winter, the worst of the conflict was over. I was thirteen, born in India of British and Anglo-Indian parents. No one ever molested me, not in Delhi, not in Dehra. Now I strolled across our extensive maidaan, to one of our cinemas. The film was called Blossoms in the Dust.

Ten minutes into the showing of the film there was an interruption, the lights came on, and the manager made an announcement.

‘I’m sorry, but we must discontinue the show. We have just received news that Gandhiji has been shot.’

GANDHIJI was no more.

I walked home through a town that was strangely silent. No riots, no slogans on the streets. The country was in shock. The assassin was a man whose strong ideological differences with the views of the Mahatma had driven him to take the life of the man who, more than any other, had been on the forefront of the long march to freedom.

In time, the country recovered from this tragic setback.

India always recovers from foreign invasions, colonial exploitations, famines and floods, quakes and cyclones, and epidemics on a grand scale.

Sometimes it takes time, but India recovers.

The seasons pass, the crops come up, the mangoes ripen, the monsoon comes and goes, the snows melt, the Ganga flows…

Excerpt from ‘A Little Book of India: Celebrating 75 Years of Independence’

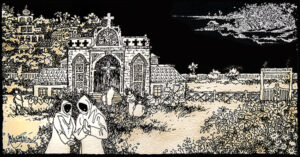

Illustration by Suvamoy Mitra