I do not have a favourite among Satyajit Ray’s films but Nayak (‘The Hero’, 1966) is one that I have seen several times. Although it is among the few films for which Ray wrote an original script, Uttam Kumar’s stardom is in competition with Ray’s authorship — in keeping with the focus of the film as an examination of cinema itself.

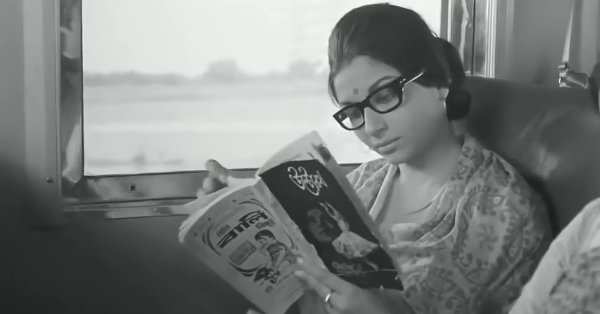

Arindam Mukherjee (Uttam Kumar) is taking the train to Delhi to receive an award, having failed to get a ticket on a flight and seeking to avoid the press after a fight in a nightclub the night before. Journalist Aditi Sengupta (Sharmila Tagore), though she dislikes Bengali cinema, seeks an interview with Arindam for the magazine she edits: Adhunika (‘The modern woman’). They strike a deep connection as they talk and the journalist realises that being a star is not what it seems. As they near Delhi, she tears up her notes as she feels that printing reality will damage his stardom. He asks if she will write from memory and she answers ‘Mone rekhe debo/I will keep it in my mind’, as she walks away while he is surrounded by his fans.

The film is deeply enjoyable aesthetically for many reasons — the sheer beauty of Uttam Kumar and Sharmila Tagore, their styling; the sensitive and convincing acting; the structure of the film; the striking images; and the fabulously recreated train itself.

The film has an old theme — life as a journey, finding the world on a train. Yet Ray’s attention to all the characters on the train is deeply engaging. All of them have some connection to the main story, but each is a character study in him or herself. Also, several have a view on cinema.

The sheer ghastliness of Haren Bose, with whom our hero shares his compartment, for one, is brought out beautifully. First, his wife and child seem too young for a man of his age and status, then we realise he is expecting favours from Molly, the wife of Prithish Sarkar, in return for helping the latter with his work. Sarkar, in turn, is willing to encourage his wife to flirt with Bose but won’t let her pursue her dream of being in films. Bose thinks films are just another reflection of India’s backwardness, while Aghore Chatterjee is an old man who thinks everyone lacks moral fibre.

Apart from Aditi, all the women on the train are film enthusiasts, adore the star who shares their journey and adopt a devotional attitude towards him – regarding him as godlike, even likening him to Krishna with his gopis.

The theme of ‘mone rekhe debo’ is also carried through the fact that we, the audience, are given access to some aspects of Arindam’s interior world, which even Aditi cannot reach. His dreams and flashbacks, only some of which he reveals to her, are framed by the journey made in the film.

For instance, Arindam’s nightmare which begins with him running around happily in piles of money before they turn into quicksand. In the nightmare, his mentor, Shankar, is in a position to save him but lets him go under. Later, Shankar reappears in another flashback as a man of the theatre who stages plays for Durga Puja and says that film actors are just puppets in the hands of others, rather than artistes in their own right.

Arindam’s flashbacks also include a conversation with Mukund Lahiri, an actor who survived the transition to sound in cinema but not to realism. He raises one of Arindam’s greatest fears, that of failure and the crash that will inevitably follow reaching such heights.

Arindam is also aware that stardom means losing friends. Biresh, his friend, wants to mobilise Arindam’s stardom to rally striking workers, but Arindam knows that this will damage his image and flees the scene. He knows also that women will be willing to engage with him physically, for gain or otherwise. It is also made clear that the brawl mentioned at the beginning of the film was a fight he had with his heroine’s husband. This is recalled in another nightmare where the guests at a party are all wearing dark glasses just as he had been when he brushed her off on a phone call earlier in the film.

Aditi’s acumen as a journalist is validated as she penetrates the façade of his stardom but she puts decency before her work as she is also able to see beyond Arindam’s star image to the real man, lonely, vulnerable as well as a kindly individual. When she understands that that she is seeing him at a near-suicidal moment after he has been drinking and taking sleeping pills, she quietly ensures he goes back to his compartment before she leaves for her own.

Ray’s careful crafting and direction allow him to explore the concepts of charisma, celebrity and stardom at length. He was aided in this by having two great leads, Uttam Kumar the Mahanayak (‘Great hero’) playing the eponymous Nayak (‘Hero’) and Sharmila Tagore, his heroine, who was at that point in time a star in Hindi cinema, playing the journalist. Each aspect of their characters in the film is carefully mounted, from her dark-rimmed spectacles to his two-tone shoes.

Ray shows how we conflate the character with the star, confusing Arindam Mukherjee with Uttam Kumar, a person distinct from Arun Kumar Chatterjee (Uttam Kumar’s real name). Uttam Kumar was taking a risk playing the star, showing the ‘man behind the curtain’. Was it Ray’s own ‘stardom’ as a director that convinced him? No one else could have played this particular role as Ray’s other great hero, the late Soumitra Chatterjee, though a great actor whose roles in cinema have made him a legend, is not star enough.

The question is why Uttam Kumar was such a big star in Bengali cinema, as well as a major cultural figure, yet is not as well-known beyond this world. Clearly such a beautiful, charismatic man, with the innocence of a child in his soft eyes and unruly hair, and a smile that could make the toughest academic melt, could have worked — and attained success — anywhere, say Hindi films.

Ray did work with stars but only as actors. Therefore, the Uttam Kumar of Chiriyakhana (1967) was the hero but not presented as a star unless we take his character, detective Byomkesh Bakshi himself to be a star. Ray always presented Sharmila as an actress rather than a star. Perhaps this was easier because her star status was with respect to the Bombay (Mumbai) film industry. It is possible that Ray could not work with Uttam Kumar beyond these two films as his stardom in Bengali cinema was simply too overwhelming.

Ray’s look at a ‘star’ in Nayak is far more nuanced and layered — as a celebrity, a person who is admired and adored but mistaken for the characters he has played and whom the audience wrongly feel they know in real life. Arindam Chatterjee is not just a talented, handsome and successful man who is not happy but a complicated figure of a Bengali man who is seeking his place in the world.

The question is why Uttam Kumar was such a big star in Bengali cinema, as well as a major cultural figure, yet is not as well-known beyond this world. Clearly such a beautiful, charismatic man, with the innocence of a child in his soft eyes and unruly hair, and a smile that could make the toughest academic melt, could have worked — and attained success — anywhere, say Hindi films.

What made Uttam Kumar such a huge star in Bengal beyond his looks and his talent? What did the figure of Uttam Kumar as a gentleman, a ‘bhadralok’, mean to his audiences during those turbulent years of Bengal’s history?

The recent elections show the complex relationship between West Bengal and the rest of India, an equation often smoothed over in the ‘all Indian’ nature of the Hindi film. Nayak shows the journey from Calcutta/Kolkata to Delhi, from the former capital to the present seat of power. The star isn’t interested in the award but wants to get away from the press, only to find a journalist who understands him. Note that these awards were not held in Bombay (Mumbai), the centre of the film industry. Nayak is about a more complex journey than that of an award-winning star.