Calico pahuch gaye, madam” says the cabbie and I alight, looking right and left for a sign of the fabled textile museum. All I can see are eight-feet-high walls that guard islands of affluence in this, the prosperous city of Ahmedabad.

I start walking along a blinding white wall that seems to enclose a luxuriant garden – swaying treetops peek from within, with an occasional riotous bougainvillea spilling over from inside. At once, the wall is broken by a huge wooden doorway in the Gujarati haveli style that looks — and is —about two centuries old. Set in the wall is a discreet brass plaque admitting that this, indeed, is the Calico Museum.

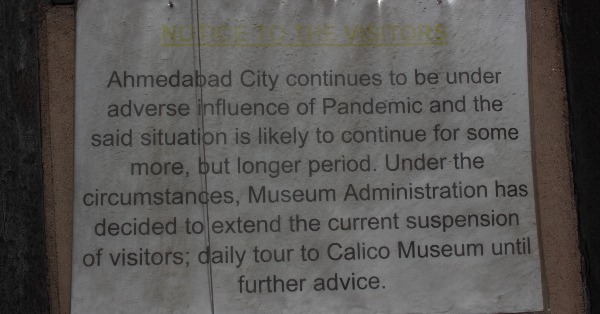

But admission of any other sort still seems hard to gain. There is no visible bell. Voices heard earlier in the week about the ‘deliberate inaccessibility’ of Calico echo in my mind. I rap on the heavy door, then thump on it, before sending up a hesitant “Bhaiyya, koi hain?”

The small eye-of-the-needle door swings inwards. A wizened face almost as old as the door asks me my business. The reactions of locals when they heard we wanted to do a story on Calico run through my mind as I wait for entry. These ranged from smirks, calls of ‘brave’ and most astonishingly, ‘good luck’ from an immediate member of the family that owned the museum! However, they had all ungrudgingly shifted their timings around to accommodate the granted-at-the-last-minute appointment. It was as if the Calico Museum was a cantankerous old dame, who, in spite of her crotchetiness, demanded respect and consideration.

The smaller door is unlatched again and as I step over the threshold, there is a sense of achievement. Undeniably, this feeling of ‘success’ at simply getting in is yet another proof of exclusion. Local cultural practitioners we had met over the previous few days, from owners in swanky galleries to artists in chawls, had passionately questioned the worth of institutions such as Calico. Visits to other spaces in that very city – spaces that cried out at, and sometimes decried, the islanded exclusiveness of the Calico – seemed to underline the view that the museum was a symbol of class privilege.

Yes, the museum had to be questioned. Not its unimpeachable work, but its ethos. Umpteen reviews online appreciating the guide’s erudition, but bemoaning her haste; complaints about inaccessibility from international textile experts travelling expressly for this purpose; the regulations on time spent in front of the exhibits, the prohibition on sketching — were all valid grounds to mount a subtle challenge.

On the other side of that door was a lush garden, rich with mature trees, and everywhere the fragrance of madhumalati. Candy-coloured butterflies flitted about and crayon-bright parakeets swooped from one branch to another, to a soundtrack of constant song. And at the end of a serpentine pathway was the gracious old building of the Haveli Museum – one part of the Calico Museum of Textiles.

On the other side of that door was a lush garden, rich with mature trees, and everywhere the fragrance of madhumalati. Candy-coloured butterflies flitted about and crayon-bright parakeets swooped from one branch to another, to a soundtrack of constant song. And at the end of a serpentine pathway was the gracious old building of the Haveli Museum — one part of the Calico Museum of Textiles.

Here, I was met by Ashok Mehta, director of the Calico Museum, and Dilip Sheth, manager. The two gentlemen, while unquestionably hospitable, seemed rather puzzled by the insistence on doing a story. However, as professionals, they were fully prepared for the ‘interview’ — three catalogues and some publications were at the ready to cut short any demands for information already in the public domain. “This will give you all you need,” said Mehta, while Sheth explained how to requisition any photos we might need. This done, they offered me tea and then sat with politely questioning looks on their faces. Was there anything else that they could help with?

Yes, there was. What was their perspective on how the Calico Museum saw itself with respect to the world outside its ‘Secret Garden’ like walls? How did they see their relationship with the general public? What did they think about outward communication? What it means to be a museum is being questioned and challenged all over the world today, modern thought and modern technology is transforming museums from spaces of looking and learning to spaces of interaction, participation and engagement — had the Calico Museum entertained questions about its own continuing significance? There were questions as well on private collections, on family Trusts.

But, their straightforward sense of purpose disarmed me immediately. “Conservation, conservation and conservation — this is our only commitment,” declared Mehta.

He continued, “We do not want to exclude, but our primary task is to conserve all the precious artefacts in our care. The Calico Museum is a place of interest for many. We have been conducting visitors’ tours for over five decades. And we always have to restrict bookings, deny admissions, suggest alternate dates. This applies equally to textile experts, cultural historians, ministers, diplomats and members of the public.”

Okay, so the Calico Museum is notoriously difficult to access for all. But, what is the point of a museum if not to educate as many as possible? And, why is limiting numbers important?

The response is crisp. “Two very strong reasons. One; human pressure beyond a certain number compromises the artefacts. Limiting exposure to untrained human agency is a must for conservation — especially in Gujarat’s climate. We have to maintain the atmosphere at conditions optimum to preservation. Remember, exposure to even one camera flash can undo years of care. So fragile are the objects that we need to engage foreign experts who have the knowhow to light an exhibit without causing any damage. But, even with the best efforts, the collection will suffer damage. So, if we have to limit the number of visitors, we will. People do have access. Just that this access is regulated, not limited.”

“Two; education and awareness. Each visitor must get their effort’s worth and the benefit of the guide’s time and her expertise. Lesser the number of people per tour, easier it is to attend to queries. Our visitors are mostly experts and serious enthusiasts, so each question merits that time and attention. The only casualties are people who want to tick this off their to-see list. But, those who genuinely want to come, will manage. Just as you have,” Mehta smiled.

The Calico Museum is completely privately funded and managed by the Sarabhai Foundation, which neither solicits nor encourages government funding. The Museum is also consciously kept free for visitors. Said Mehta, “With funding, with fees, come demands. While such demands are legitimate from paying stakeholders, they are usually not sensitive to the need and purpose of the Museum. So, we consciously work to avoid an environment that can create such demands.”

Successive governments — both Central and State — have indicated they would like “a hand in the pie”. But the Museum has held firm. As a result, the government now maintains a hands-off policy. “They know we are conserving national treasures at our own expense and with our own expertise — and that is enough,” Mehta said.

The expenses are considerable, especially on upkeep. “The building itself is a heritage structure housing even older antiquities. This means regular upkeep – repairs are always ongoing. Our gallery is designed for an affective experience, making climate control challenging and expensive. Services of conservation experts such as Nobuko Gazhitani, a consultant from Japan who specialises in preserving artefacts in tropical climates, have to be factored in,” said Sheth.

No wonder that on the Museum’s balance sheet, upkeep costs are higher than the outgo on salary. Considering that the Trust employs 125 people to take care of the 23-acre property, one can estimate this cost. Sheth informed us that there is another aspect of the Museum. “The Retreat is also a designated botanical garden — a much-needed resource for students of Botany from Ahmedabad University to access rare varieties of plant life, which in turn attract butterflies, birds and smaller animals as well. Maintaining this is also a big commitment,” he said. This also explains the unusually large number and variety of butterflies and birds I had noticed on my way in.

It is clear that the staff believe they are serving the nation in their own way by preserving this collection with passion and purpose. “I had only one brief — do not give in to any sort of pressure. Conserve, conserve, conserve. And so we have,” said the director. He added that the Sarabhai family has enabled the team to act with single-minded purpose by providing them confidence and security. “The family believes in joint responsibility. We know we will never face blame if we refuse out-of-turn requests, whosoever it might be.”

It is clear that the staff believe they are serving the nation in their own way by preserving this collection with passion and purpose. “I had only one brief — do not give in to any sort of pressure. Conserve, conserve, conserve. And so we have,” said the director.

Mehta then gently directs me to the Encyclopedia Britannica entry for ‘museum’. It says, “Museums have been founded for a variety of purposes: to serve as recreational facilities, scholarly venues, or educational resources; to contribute to the quality of life of the areas where they are situated; to attract tourism to a region; to promote civic pride or nationalistic endeavour; or even to transmit overtly ideological concepts. Given such a variety of purposes, museums reveal remarkable diversity in form, content, and even function. Yet, despite such diversity, they are bound by a common goal: the preservation and interpretation of some material aspect of society’s cultural consciousness.”

“Those of us in the business of conservation cannot be participatory beyond a point. Calico’s role is not to redefine itself. It is to live that definition of a museum where artefacts are conserved, and where interested people can come to learn,” Mehta said.

He continued with a wry smile, “It is a tough task to even try to balance the needs of conservation of the old with the habits and appetites of the present. So, we don’t try. We are not participating in a popularity contest. If we did, we know we would lose.”

I have to agree. There’s no denying that expecting a ‘participatory experience’ from all museums is as much an “appetite of the present” as taking photographs in museums in order to post on social media.

As the interaction draws to a close, it is clear that entities such as the Calico Museum face a strange conundrum. With artefacts of a different time in their guardianship, fighting a daily battle against the forces of time, they stand accused of being removed from the realities of the present.

Perhaps, it is not for them to change. Perhaps, it is for us to understand that however much living museums gather momentum, however many participatory museums work towards catalysing individual and social change, museums of the old school that invest all their resources into conserving will always remain vitally important.

At the same time, such museums must remain open to challenges, must ask and answer questions, so that they do not stay embedded in antiquated thought processes while taking care of antiquities. Because, not only do such museums keep our history alive, they have a significant role to play for both our present and our future possibilities. Without exaggeration, such museums remain imperative for our future.

As for what the Calico Museum exhibits, as the director rightly said, there is more than enough online about them. We will say just one thing. If you ever do visit Ahmedabad, book your slot at the Calico Museum well in advance. The treasures are theirs but you will be the one richer for the visit.

Knowing Calico: The Calico Museum of Textiles (managed by the Sarabhai Foundation since 1982), and the galleries of the Sarabhai Foundation are both located in The Retreat in Shahibag at Ahmedabad. The Museum is both a testament to and a raconteur of Indian textile traditions through the ages. From textiles of everyday use such as tents and awnings used for functions and ‘palampores’ or bedspreads from the 18th century, to occasion wear such as dressy ‘patkas’ (a stole-like garment worn by noblemen in Rajasthan, Gujarat and in the Mughal court) from medieval times and sarees embellished with the most exquisite sozni or phulkari embroidery, the Calico Museum is a magnificent repository of the fabrics of our nation. The galleries are home to a wondrous collection of south Indian bronzes, Vaishnava picchavais, Jain art as well as miniature paintings.

Anamika Debnath, Professor, National Institute of Technology, Kolkata, under the Ministry of Textiles

‘Calico Museum is a wonderful repository of samples and know-how about some of the greatest textiles of the country. It is a priceless resource. I have visited thrice and to use student-speak, I was blown away. The best part is that only really interested people make the effort to go.’

‘They are brilliant at conservation. I know that timing and access is strictly regulated to help them maintain the fragile pieces. They are not publicly funded, and their stated responsibility is conservation – why should anyone have any issues with this? If regulated accessibility is how they want to preserve their artefacts, then that’s that. Governments do it regularly when it comes to conservation of fragile heritage sites. Everything does not need to be accessible to everyone. Especially when the priority is conservation.’

‘I am not in favour of the notion that governments should be the custodians of every precious thing. In reality, governments do not have the resources, the expertise or the manpower to conserve resources such as this. Also, the changing policy of successive governments can create and has created irreparable damage in the past. If the collection remains as beautifully conserved as in the case of Calico Museum, I am all for it.’

‘They are wonderful to experience. But I also understand that not all artefacts can be touched. Of course there are ways of making museums more relevant to people. But not every collection/museum needs to serve the same purpose.’