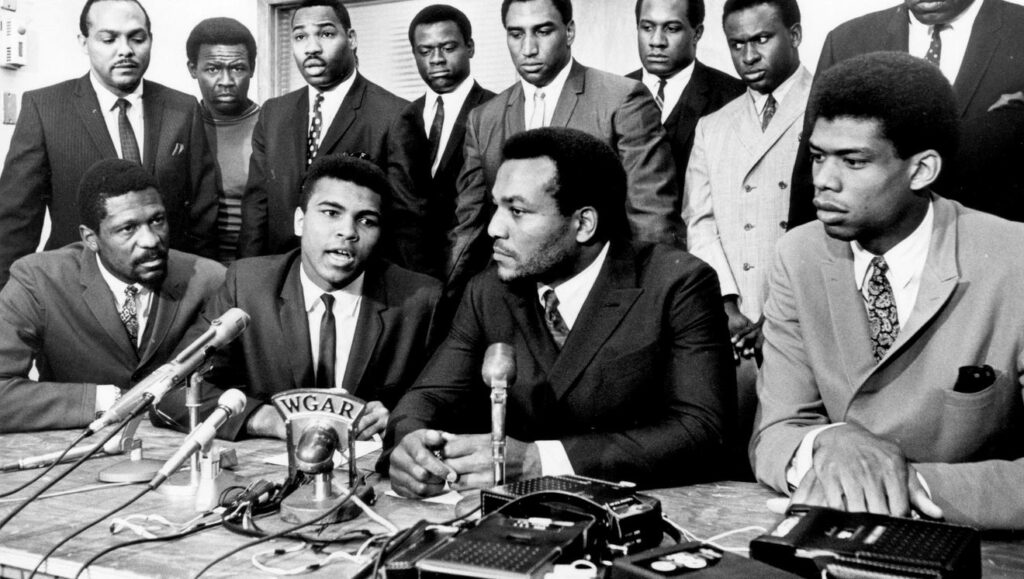

They said, ‘We don’t serve niggers here,’ I said, ‘That’s okay, I don’t eat ‘em.’ But they put me out in the street. So, I went down to the river, the Ohio River, and threw my gold medal in it.”

— from Muhammed Ali’s autobiography, The Greatest

A piece of gold sinking to the river bed, a raised fist, a bowed head, a woman simply running alongside men, and most recently, taking a knee – the sports arena has on several occasions, made protest assume a seismic resonance across communities, countries and time.

What makes some athletes take that step? Are their actions spontaneous or are they clearly thought-out symbols of resistance? Why have other forms of injustice not been protested as much as racism has been, on the field of sport? And crucially, what were the consequences for those who walked down this path? Protest recently made its way back into the sports arena in the wake of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement with sportspersons taking a knee as a mark of solidarity for all those who have faced and suffered racism. Has ‘taking the knee’ brought back the realisation among sportspersons that they can be agents of change? Perhaps answers will be clearer in a post-pandemic world.

Former West Indian fast bowler Michael Holding famously broke down on camera while talking about racism and discrimination even within coloured communities. It was a moment that sharply brought into focus the reason sporting greats feel compelled to speak out. It was a mirror to the fact that several all-time greats had to fight adversity and injustice to achieve success. Discrimination is the child of these circumstances and when a sportsperson emerges from this morass, he or she is carrying a scar, an open wound that smarts, hurts and often festers even when success comes calling.

Sometimes the politics of the time compels a sportsperson to take a stand that she knows will ruin forever her career and life. An example that has often been forgotten is Vera Caslavska, the gymnast from the erstwhile Czechoslovakia. The Czech was already a superstar when she arrived in Mexico City for the 1968 Olympics, with more gold medals than any other athlete in the history of the sport at the time. But there was a story that was hidden behind her famed beauty and grace. Czechoslovakia had been invaded by Soviet troops barely two months before the 1968 Olympics, and Caslavska herself had been involved in underground resistance and actually surfaced just before the Games. At her events, controversial rulings denied her one gold and compelled her to share the other one with her Soviet opponent. On the podium, as the Soviet anthem played, all Caslavska did was to turn her petite frame away from her flag and bow her head. The great Czech champion had choreographed a protest that was graceful yet got her message across the world. A price had to be paid: Caslavska’s career ended that moment — she was not allowed to coach for the next two decades and had to work as a cleaner to make ends meet. Tellingly, I cannot remember the name of the Soviet co-gold medallist, and Googling seems superfluous.

The more famous protest at the 1968 Olympics was the salute at the podium ceremony of the 200m race when USA’s Tommie Smith (Gold) and John Carlos (Bronze) showed the raised fist as a Black Power salute. The salute was reflective to a decade that was marked with flashpoints of racial protests. The protest caused ripples across the sporting universe, particularly in the USA. A price had to be paid: the duo was tossed out of the Olympics village, their families received threats and the ‘Time’ magazine to their eternal shame branded the protest as ‘Angrier, Nastier, Uglier.’ Such were the times that the Australian silver medallist Peter Norman, who supported the protest, was never allowed to compete for his country again. Interestingly, even 32 years later, he was not part of the torch ceremony or celebrations for the 2000 Sydney Olympics. A few years later, however, Smith and Carlos were pallbearers at Norman’s funeral in 2006.

Katherine Switzer had a happier closure to her act, that was protest through performance and presence. The long-distance runner decided to compete in the men’s only Boston Marathon. She was running alongside her coach, with her boyfriend, a rather well-built hammer-thrower at hand. Race official Jock Semple tried to rip her race number off her vest, and at some point, Switzer was running two races, one away from Semple and the other, the marathon itself. Fortunately, the sport realised that course correction was required, and Switzer legitimately won the New York Marathon a few years later.

No article on crusading sportsmen can be complete without the mention of Ali. He protested racial injustice right from the start of his career, refused the Vietnam war draft and never missed a chance to expose the inherent prejudice in American society and Christian iconography. Ali wanted change and yes, a price had to be paid: He was never allowed to take part in the US boxing championships and not granted a boxing licence in any state between 1968 and 1970 when he was at the prime of his career. But Ali being Ali just carried on and became the world’s first truly universal sporting icon, conjuring up sporting magic from Atlanta to Manila and New York to Kinshasa. Ali returned to the Olympics in 1996, in Atlanta, where he lit the flame in one of the most moving moments in the event’s history.

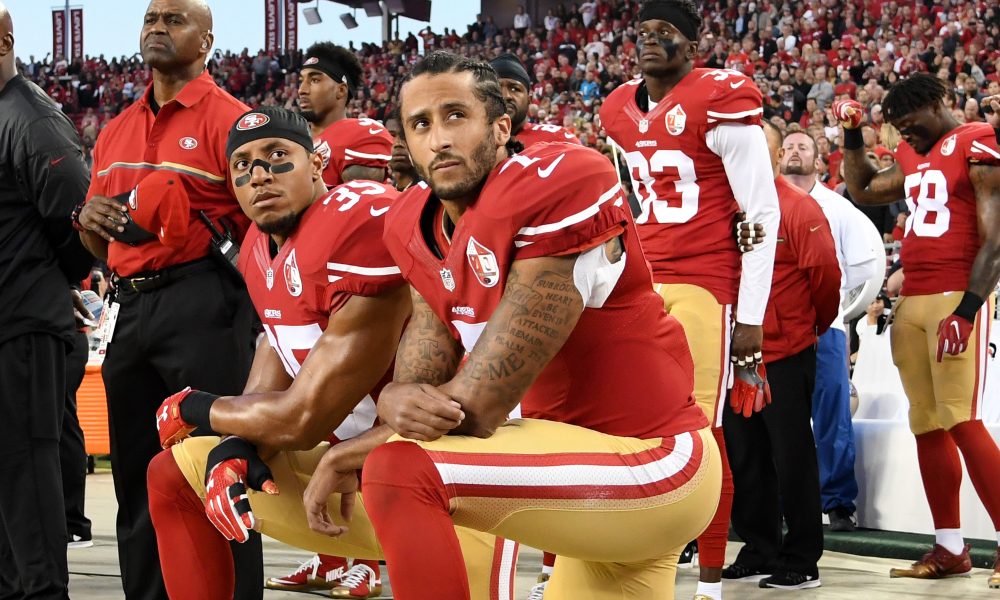

Today, protest is voiced on Twitter and both support and backlash are instantly registered. The difference is, however, between comment and action, and between using the sports arena as the centre of change rather than a social media platform. Which is why Colin Kaepernick, a quarterback in the National Football League, is an important figure. His protest of kneeling during the US National Anthem in 2016 to protest racism became a symbol of protest grew with time and through tragic circumstances. By 2020, the killing of George Floyd made ‘Black Lives Matter’ a global cry embraced by sportsmen across the world. Every Premier League match today starts with the teams taking a knee as a global audience of millions tune in. Does it have an impact? It is hard to tell, but the gesture tells aspiring sportspersons that they must try to be the change.

Which brings us to India, the birthplace of ahimsa and peaceful protest. Where movements as divergent as the Chipko Movement and street theatre flourish, our stadia and sports spaces are inexplicably arenas of conformity, abiding by rules and not challenging status quo. According to our ancient texts, a mentor once asked a disenfranchised child who was secretly learning from him to pay for his knowledge with his thumb. The mentor’s name now adorns the nation’s highest coaching prize, the Dronacharya Award. Social justice and sporting returns perhaps have never marched hand in hand in our country.