The Performance of Practice

Among the many and varied ongoing changes in the sphere of Hindustani classical music, one that perhaps requires discussion concerns the rapidly changing interiority of the process of riyaaz. Riyaaz or sadhana, for those who prefer the latter, conventionally involved a solitary immersion in a systematic, disciplined practice that aimed at overcoming weaknesses and limitations, and nourishing one’s strengths as a musician. Sometimes these sessions would also be conducted under the supervision of a guru or mentor. A tabla accompanist could also be present in some sessions, but once again, the participation of the accompanying musician was permitted for the purpose of practice alone and not performance.

For all practical purposes therefore, riyaaz remained a private space that was intentionally kept away from the public gaze. This was a space where, without experiencing any embarrassment, you could stumble as you negotiated a paltaa (vocal exercise) and repeat the exercise diligently till you got it right, even if that meant weeks, months or more of tireless riyaaz. The reward, if any, came when you used your riyaaz in time and to your advantage in executing a breathtaking taan that was perhaps rewarded by thunderous applause during a performance. But the inherent difference between riyaaz and performance lay in the former being a personal, private, closed space where outsiders and onlookers were denied access intentionally, and the latter being an open, public platform where access was provided to all, either free of charge or through membership or ticketing.

In the past one often heard anecdotes of musicians taking great pains and even resorting to stealth and planning in order to be able to listen in to the riyaaz sessions of great artistes. There was absolutely no question of being provided open access to a riyaaz session. Today, it is not uncommon to see a Facebook post or an Instagram video with a caption saying — ‘just a little riyaaz in X,Y,Z raag on popular demand’.

This basic difference between the two spaces seems now to be gradually blurring, especially on social media platforms that are becoming increasingly popular with musicians. In the past one often heard anecdotes of musicians taking great pains and even resorting to stealth and planning in order to be able to listen in to the riyaaz sessions of great artistes. There was absolutely no question of being provided open access to a riyaaz session. Today, it is not uncommon to see a Facebook post or an Instagram video with a caption saying- ‘just a little riyaaz in X, Y, Z raag on popular demand’. Indeed, the decision to grant or withhold access to a riyaaz session must always remain with the artiste. But the presence of an onlooker, however silent and unobtrusive, turns the riyaaz session into a performance, albeit one that is conducted in the artiste’s home and without the formality associated with the concert proscenium.

Taaleem or training sessions too are conventionally closed spaces where onlookers are not permitted. It is during these sessions that the guru or ustad hones and moulds a student, working on the student’s weaknesses with brutal candour and strengthening the disciple’s talent. A spade is called a spade during these sessions, often with no concessions and niceties. The moment an audience is given access to these sessions, two performances could begin to play out simultaneously. The guru begins to perform the part of a guru, often choosing to appear more magnanimous and compassionate than in the closed door sessions. No guru will want to be seen dressing down a disciple mercilessly to the point of reducing him or her to tears. And when on camera, the shishya too performs the part of an ideal shishya, subtly altering the dynamics of the relationship in almost imperceptible ways. Exaggerated subservience, humility, appreciation could become part of the role play.

The logic behind maintaining riyaaz and taaleem spaces as no-audience zones is simple. These are in a sense, preparatory study spaces that require an artiste to look inwards and surrender. The process is an endless involvement with grit, grime, sweat, endless hours of hard work, and demands detachment from any possible distractions, and unwavering concentration that really cannot be put on display. The moment they are on display, they invariably become staged performances of riyaaz and taaleem. The visual demands of social media platforms also play a part in the staging and the addition of elements that might never have been a part of the original riyaaz space. Propped up in front of a bunch of cushions in a pretty corner of the house, sometimes with string lights strewn in the background, a few houseplants arranged strategically to add colour to the visuals, a mini-performance of a riyaaz is staged and shared. The artiste may perform a few dazzling exercises to drive home the riyaaz angle, but these are the exercises that they have already mastered, not the ones that they still stumble or waver through.

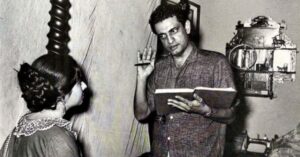

In rare instances, artistes have generously shared their taaleem sessions with the public, providing music students and music lovers an opportunity to witness the wisdom and mastery of their gurus. A wonderful example is available in the form of audio recordings of taaleem sessions where the eminent vocalist Ulhas Kashalkar is being trained by his guru Gajananbuwa Joshi. It is important to remember that the taaleem sessions themselves were conducted without an audience, or perhaps in the presence of a few senior disciples or accompanist, and it the recording of those invaluable sessions that is now being shared for educational purposes.

In today’s world we are living online lives where privacy of all kinds is often breached. It is not surprising therefore, to find that the closed doors behind which riyaaz and taaleem were conducted, are being thrown open. Whether access to these spaces should be provided, and whether or not it is at all possible to calibrate the access that is provided in order to retain their basic integrity, are personal decisions that each artiste will need to make.