Jungle Nama is an adaptation in English of a famous story from the Sundarban, the legend of Bon Bibi. In the villages of the Sundarban the legend exists in many forms: there are at least two printed panchalis, both of which are entitled Bon Bibi Johuranama. One was composed by Munshi Mohammad Khatir, and the other by Abdur Rahim Sahib; both are thought to have been written in the late 19th century.

Both of the Johuranamas, as is usual with panchalis, make extensive use of the poyar meter (chhanda). Keeping to the spirit of panchalis I have retold the legend in verse, using a variation of the Bangla poyar meter. In my English adaptation of the meter, each line has, on average, twelve syllables, so each couplet has twenty-four syllables. Every line also has a natural break or caesura. However, Jungle Nama is not a translation: it is a free adaptation which does not adhere closely to printed versions of the legend. Jungle Nama is not intended to be a definitive or accurate version of the narrative; it is rather, yet another interpretation of a story that already exists in many forms.

In the Sundarban the legend of Bon Bibi is also performed by traveling jatra companies, usually around the time of Makar Sankranti, in January. These tellings of the legend differ from the panchalis in many respects, and each staging tends to highlight different episodes of the legend. The jatra performances tend to be centered on the most dramatic episode in the legend, the story of Dhona, Dukhey and Dokkhin Rai. I too have chosen to focus on this episode, which forms the imaginative and dramatic core of the legend.

The vocabulary of the Bon Bibi Johuranamas is extraordinarily hybrid, being heavily influenced by Persian and Quranic Arabic. The texts include many words that would not be familiar to speakers of standard Bengali. The story is remarkable also for the fluency with which it blends elements of Hinduism and Islam. Bon Bibi is seen by many as a goddess-like figure; but in printed versions of the legend she is actually presented as a female pir, the daughter of a Muslim fakir. Whether the story belongs to one faith tradition or the other is impossible to decide, and nor is it important. All across the Sundarban, no matter whether in West Bengal or Bangladesh, no matter whether Hindu, Muslim or Christian, the great majority of forest dwellers are devotees of Bon Bibi. In that sense the legend is a good example of the syncretism of Bengali folk culture.

The basic message of the Bon Bibi legend is that it is essential to place limits on human greed in order to preserve a balance between the needs of humans and those of other beings. This message does not belong to any one religion: it recurs frequently in the stories of Adivasis and forest peoples around the world. The same idea lies at the heart of another legend that is indigenous to eastern India – the story of Chand Saudagar and Manasa Debi. These are essential values for this era of planetary crisis, and it is on them that my adaptation rests.

For the people of the Sundarban, the legend of Bon Bibi is much more than a story: it defines a way of life. In the Sundarban life is extremely difficult in many ways, yet the people who live there have an amazing stoicism and good humor. Just as the boundaries between land and water are very fluid in the Sundarban, so too are the lines between different groups of people. No matter what their caste or religion the people of the Sundarban all respect the legend of Bon Bibi. The story provides a kind of ethical charter – almost a law – for how people should relate to the forest, and it has an enormous influence on the lives of the inhabitants.

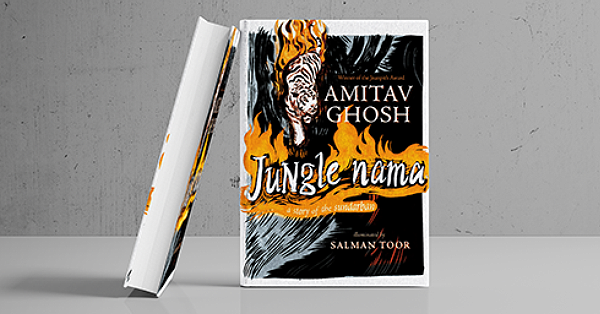

In my 2016 book, The Great Derangement, I wrote that in order to respond to the challenges posed by our various planetary crises, writers will need to experiment with new and different forms: the old forms (like the conventional novel etc.) are simply not able to deal with some of these challenges. One reason for this, I feel, is that ‘serious’ literature has become too strictly focused on words. This is actually a fairly new development: in the past, images and pictorial elements had always figured prominently in literary texts, for example in our beautifully decorated palm-leaf manuscripts, or the exquisite illuminated Bhagavad Puranas of Rajasthan, or Persian texts like the Razmnama or Shahnama, with their profusion of miniatures. In Europe too, important texts were usually illuminated, well into the age of print.

My intention, right from the start, was to create an illuminated text, in the old sense, in which word and image have parity. This meant that the book would have to be a collaboration – and this was exactly what I wanted, for I feel that one of the profoundest problems with contemporary literature is that it has become completely focused on the individual.

The word ‘illuminated’ is important here, because it suggests that the pictorial elements are throwing their own light on the text. By contrast, ‘illustrated’ suggests that the pictures are subordinate to the words: in that sense it is almost a pejorative.

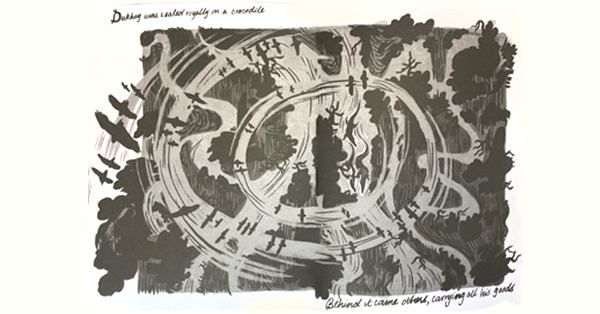

My intention, right from the start, was to create an illuminated text, in the old sense, in which word and image have parity. This meant that the book would have to be a collaboration – and this was exactly what I wanted, for I feel that one of the profoundest problems with contemporary literature is that it has become completely focused on the individual. This is true in two senses: not only are literary works produced by individual writers, working alone, but the intended reader is also an individual, reading in silence. I wanted to create a text of a different kind, a work that would be collaborative at many levels. I imagined it as a new version of an illuminated text, produced in collaboration with an artist. I was fortunate in that I was able to collaborate with a prodigiously gifted young artist, Salman Toor, who has already established himself as one of the foremost talents of his generation.

Texts like the Bon Bibi Johuranama are not usually read silently, by a single individual – they are chanted, performed and sung. Jungle Nama is intended to be read aloud, with musical accompaniment. In this again, I have been fortunate to collaborate with a very gifted young musician, Ali Sethi, who is currently working on an audio version of the text. I have heard parts of it, and it is completely enchanting.

https://www.facebook.com/HarperCollinsIN/videos/454633432225808/