Queering Our Folktales

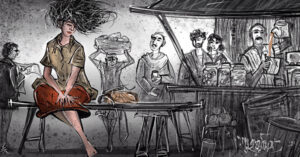

Even as Hindi films about small towns introduce India to Indians as Yash Chopra once took us to Switzerland, questions like these continue to get asked on newspaper websites: ‘Is it true that there are homosexuals even in the small towns?’; ‘Has there ever been a Pride march in North Bengal?’; ‘Who brought the disease of homosexuality to a paradise like North Bengal?’ Reading Kaustav Chakraborty’s book, Queering Tribal Folktales from East and Northeast India, it was to the sense of surprise — and even the register of shock — in these questions that I thought of. Chakraborty, who grew up in the district town of Jalpaiguri and has been teaching at Southfield (formerly Loreto) College in Darjeeling, brings his training in literature and cultural studies to create and study an archive of queer readings of folktales from the region.

Kaustav, whom I have met only once, more than a decade ago, identifies with ‘Otherness’. That word, reduced by academia into a tent-like ‘free size’, he claims for himself for a number of reasons: his own ‘sexual non-normativity’; the ‘belittled traditions’ of the folktale when posited against ‘mainstream’ ‘classical and popular literature’, and, in that, the hierarchy between oral and written literature; and, of course, the location of where he has lived for most of his life. As I write this, I cannot not be aware of how this process of othering continues in the media — I’m thinking of how little we know about LGBT (Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender) histories in our towns and villages.

Toto is the name of a tribe that lives primarily in Alipurduar district’s Totopara, about 22 kilometres from Madarihat, a name familiar to tourists who enter the Jaldapara National Park from here. The Totos live on the banks of the Torsa river, near the border that separates Bhutan from West Bengal. Kaustav notices three patterns of thought and characterisation in their folktales: ‘from leading grandmother to misleading witch; dissident intimacies; evil as emancipation’. The ‘erotic’ relationship between young men and the grandmother figure, which is evidence of a sexual order before the impact of Hindu and Christian ways of life and legality, are found in folktales like The Pumpkin Prince, The Orphan Boy, The Story of Two Orphans and The Witch Mother.

In the folktale about the orphan boy, we encounter similar episodes of transformation. Yes, these transformations can be read as the need to escape from the demands of a compulsive heterosexual society, as Chakrabarti reveals in his inspired readings of folktales not just of the Toto community but also those of the Rabha, Limbu and Lepcha tribes.

The Pumpkin Prince is a tale about transformation, in the tradition of plants and animals changing into humans and humans metamorphosing into other beings. An old farmer couple discovers a pumpkin that pleads with them not to cut it, saying that it will help them do all their work. The pumpkin becomes their grandson. What happens after this is common to many folktales – the eldest daughters of a king rejecting him, the youngest marrying him, discovering that he was a prince trapped in the body of a pumpkin, having children, and so on, a turn of events that generates jealousy in the sisters who rejected the ‘pumpkin prince’. The eldest sister kills the youngest by drowning her in the river, fools her husband for some time, until the prince discovers his ‘real’ wife, and kills her eldest sister by throwing her into a pit dug for an areca nut tree.

Kaustav Chakrabarti reads this tale — and its different versions and variations in Toto oral history — as one of a ‘queer life’ where a person living outside the norms of heterosexual life goes through a series of relationships, from an eroticised grandmother figure to a dead wife who exists only as an ‘apparition’: ‘The tale underscores the fact that in a changed tribalscape, the desired queer life can be lived only under the disguise of a pumpkin’.

The pumpkin and the areca nut, commonly grown in Totopara and other regions in North Bengal, appear in other stories as well. In the folktale about the orphan boy, we encounter similar episodes of transformation. Yes, these transformations can be read as the need to escape from the demands of a compulsive heterosexual society, as Chakrabarti reveals in his inspired readings of folktales not just of the Toto community but also those of the Rabha, Limbu and Lepcha tribes. But reading them here, possibly collected in the English language for the first time, it is the desperation for transformation that I am most moved by — the urgent need to escape the human form and the social, but also the easy fluidity between species, from human to plant or animal or from them to the human form. These tales of metamorphosis exist in all cultures, and are an archive of desire, of experiments of the human imagination with various kinds of habitats and residencies. Reading about orphans and the treatment of the social system to such figures in these folktales from northern Bengal as slogans and songs related to the Bengal elections enter the room, I find myself thinking about my LGBT friends and family from this region. I have not seen their lives and needs being discussed in the manifesto of any political party in this election.